De Chile, Mole y Pozole: Stories from Oaxaca

Many of us love the heft of a book in our hands. We love its feel. The flexibility of old leather, the warmth of cloth, the smoothness of glossy paper, the thickness of a page. We’re taken with the graphics on the cover, the colors, the font that invites us to grab that one off the shelf.

And that’s before you open the book!

If you have kids, you know how fascinated they are, not only with the story but with the physical book itself. By the time they’re four, they get hooked on electronic media if we let them — but for many, that love of books never dies.

But like everything else in our economy, the drive for profits has led to the rise of publishing and book selling oligopolies. These mega-companies don’t want or need to take risks. So, what choices do readers have beyond “bestsellers” stamped with the New York Times approval? How do new writers from marginalized communities find their way into your book collection?

The only way is for people to do it themselves. We know Kurt Hackbarth well from his political journalism, but he’s also a fiction writer — and a book publisher.

Micropublishers — which he compares to microbreweries — create unique offerings beyond the ordinary flavors, and paper and book bindings add to the charm. What drives these community-based publishing houses (truly houses, his is in his tiny apartment) is not profit but the desire to bring new voices into the conversation.

From the beginning of human civilization, books have bonded and tied together generations and peoples — you and me — and empowered us to step outside ourselves to explore and celebrate our common humanity.

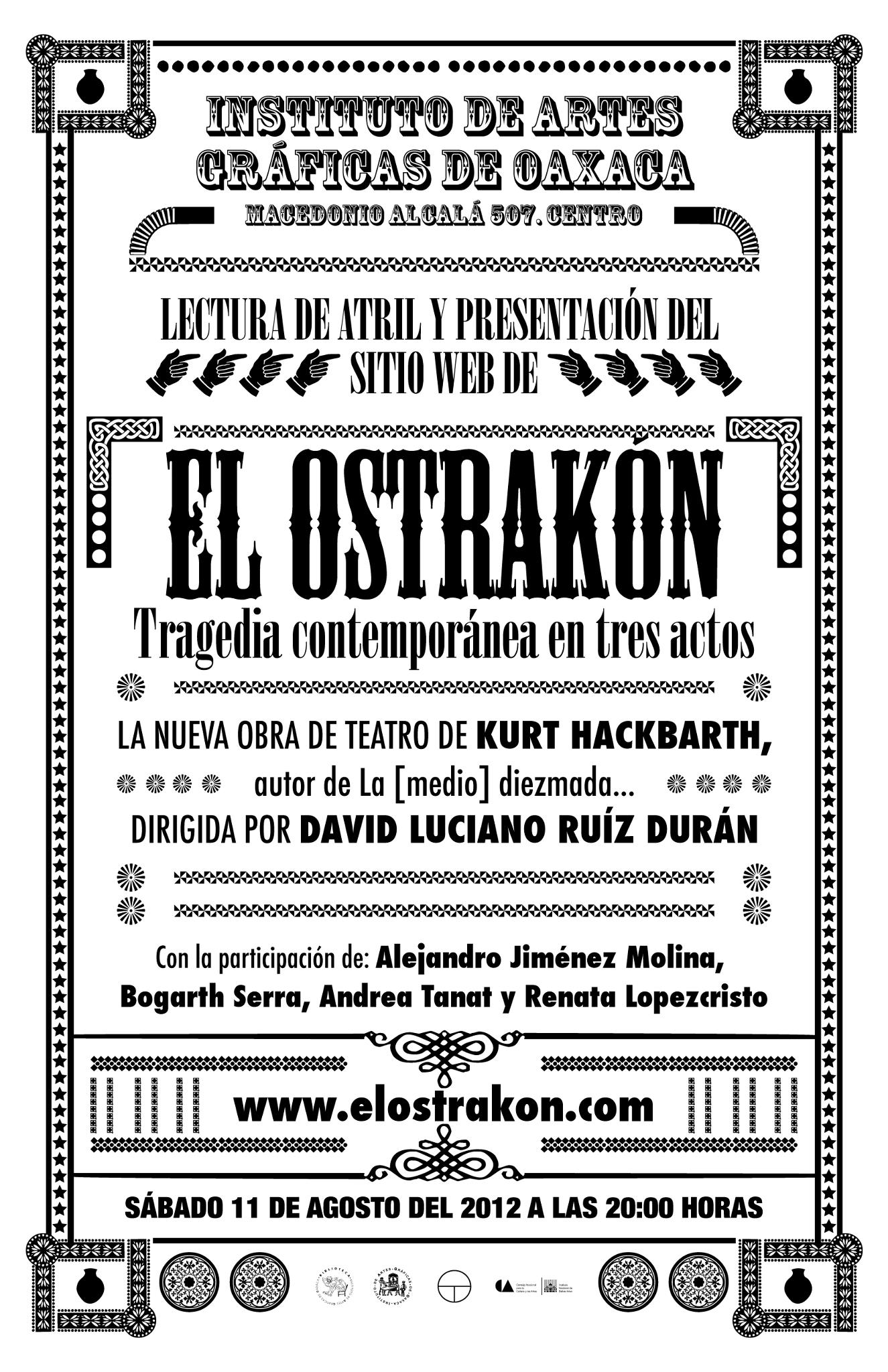

Writer, playwright, and journalist Kurt Hackbarth is a naturalized Mexican citizen living in Oaxaca. His political commentary is regularly featured in Sentido Común, Al Jazeera, Jacobin, the Mexico Solidarity Project’s Bulletin, and its podcast Soberanía. Committed to getting new writers published, he and his partner, Nidia Rojas, created their own publishing house. They just put out a new bilingual anthology of Oaxacan authors, De Chile, Mole y Pozole.

Your new anthology of short stories from Oaxacan writers is out! Are most of them indigenous? How did you decide who to include?

The state of Oaxaca does have a high percentage of people from many different indigenous ethnicities — they total about 39% of the population. There are many mestizo people, Afro-Mexican communities in the southwest and Anglos.

I live and work in the capital city of Oaxaca de Juárez. As a writer, I’ve always wanted others to also unleash their creativity through writing. For the last 15 years, I’ve taught literary workshops, including a recurring one on short story writing.

In Oaxaca, no college-level degree in literature has been available until very recently, so students have to travel out of state to study writing. The Henestrosa Library, a beautiful building, is easily accessible to all in the city. It offers a series of workshops, including mine. The people who sign up for my workshop are a real mix in age, ethnicity, and current and former jobs.

Every Saturday, we spend two hours reading and analyzing a short story, looking at the various ways stories are told and constructed. Then, for two hours, we do writing exercises. By the end of the course, participants will have completed a short story.

After a workshop ends, sometimes participants want to continue honing their writing skills, which makes me happy. I helped some of them form a collective of short story writers, the Colectivo Cuenteros. They meet weekly to give each other feedback on what they’re writing. The authors included in the anthology come from this group; I’ve known some of them for many years.

Did you choose a theme for the anthology? And did you work with the authors to bring the book to fruition?

There isn’t a theme — the only criteria is quality. Writers proposed what they considered their best stories for inclusion, but those weren’t necessarily the final choices. The title of the anthology is De Chile, Mole y Pozole, a Mexican phrase referring to a variety or assortment. And by the way, pozole is a traditional soup or stew of indigenous origins. Its base is hominy, or ground corn, Mexico’s staple food, cooked in broth with meat and all kinds of vegetables thrown in. And Oaxaca is known to have the best mole.

The anthology has a variety of voices. Some authors come from different indigenous pueblos, and others are from the Central Valleys. A few were born in other parts of the country but have come to live and work here. Many different styles of writing are included — social realism, fantasy, historical fiction, comedic, coming of age and gritty.

I wanted to bring these stories from Oaxaca to a new English speaking audience, so the book is bilingual. I’ve been to book fairs where people are looking for books of Oaxacan literature in English, and they’re not to be found. Translating was the hardest part, and I enlisted readers to ensure the translation was as true to the original in meaning and tone as possible.

There are writers — and there are publishers! You have your own publishing house. Why? Some publishers do marketing; how do you sell your books?

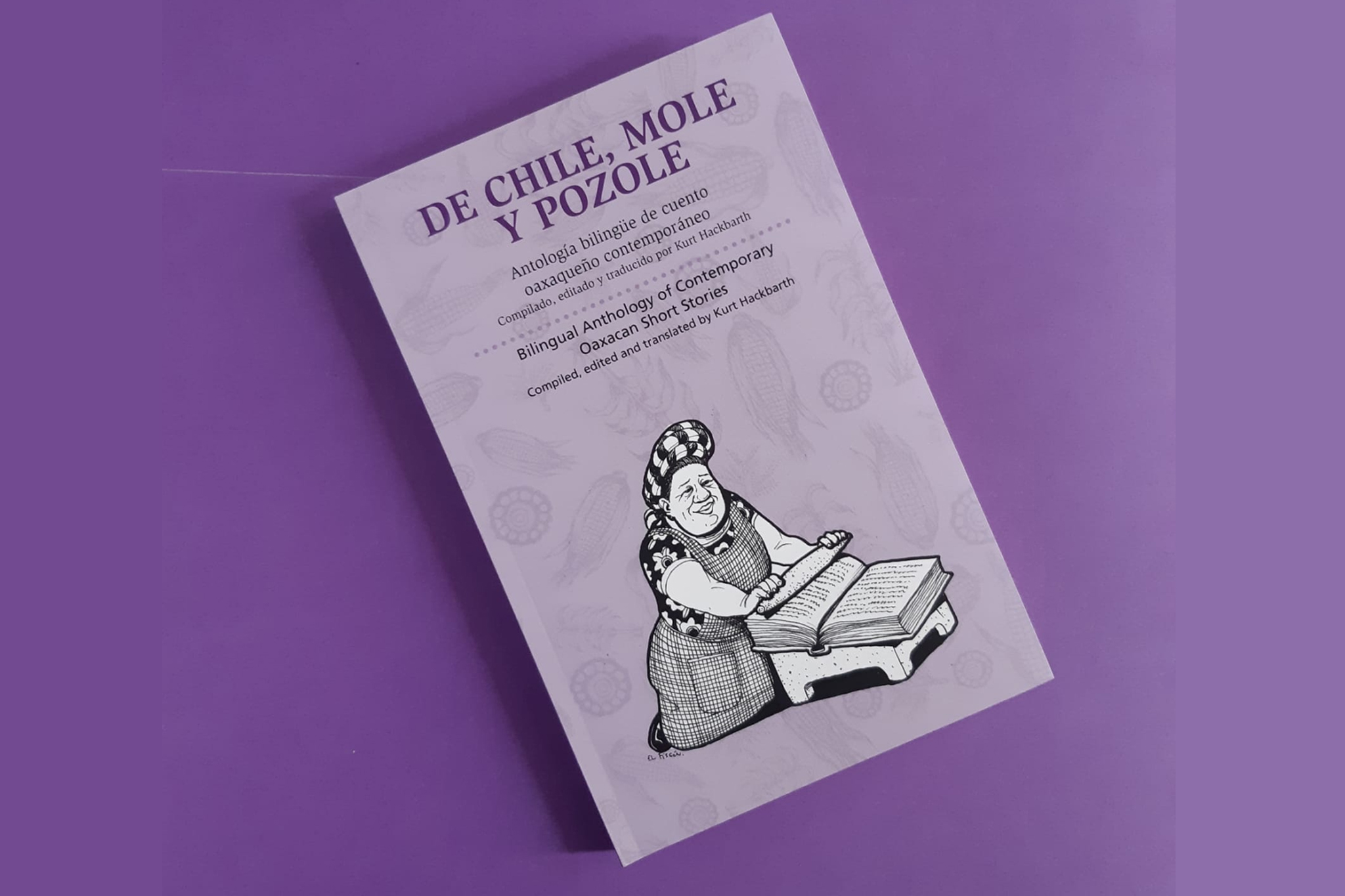

My partner, Nidia Rojas, does bookbinding, book restoration and production using local paper and materials. In 2019, we decided to start a publishing house, Matanga Taller-Editorial, out of her workshop in order to publish Oaxacan authors. We wanted to produce books that look handsome and feel wonderful in your hands, but are not unaffordable. We’ve worked with various artists and illustrators; the famous political cartoonist El Fisgón designed the cover of De Chile, Mole y Pozole.

The good news is that new small publishing houses are booming — in Oaxaca alone, we have six or seven. We consider ourselves the craft brewers of the publishing world! And for us, publishing books is a labor of love; as long as we don’t lose money, we’re ok.

For the books Nidia and I publish, we get them into local bookstores, which sell them on consignment. We do take them to book fairs across the country and also have an online store.

Mexicans love books, but they’re largely unaffordable for working-class people. Paco Taibo was named the head of the national government’s Fondo de Cultura Economica and promised to make available a huge number of affordable books. Has he succeeded?

Paco definitely shook up the Fondo. Instead of catering to urban and elite culture, he promised books for the masses. It turns out that tons of books were piled up in warehouses. He got them out and practically gave them away. This is good. But the downside is that this can wind up undercutting small publishers like us. We can’t afford to give books away.

Interestingly, one of president-elect Claudia Sheinbaum’s proposals is to create a “republic of readers.” So we look forward to policies encouraging books and independent publishers.

Most of us know you as a journalist, but you’re also a playwright and fiction writer. Would you rather focus on fiction, but journalism pays the bills? Or are they two aspects of the same purpose in your writing?

I’m equally committed to both kinds of writing; they’re complementary. In the new Mexico Solidarity Project podcast that I co-host with José Luis Granados Ceja, Soberanía, I hope we show that fact-based journalism doesn’t have to be dry — it can be entertaining. And there’s no dearth of science fiction or detective novels — such as Paco Taibo’s popular series — that have political underpinnings.

Books are part of what makes us human. We read to understand our world, to open our minds and imaginations, and simply to enjoy life.