A Century of Mexico’s Organ Grinders

This article by Ana Mónica Rodríguez originally appeared in the November 14, 2025 edition of La Jornada, Mexico’s premier left wing daily newspaper.

The profession of organ grinder, whose instrument is a symbol of urban identity and keeps alive a sound that is part of the country’s cultural heritage, faces the impact of “fake organ grinders”, who “are flooding the city, with painted wooden boxes, pre-recorded MP3 music and who makes melodies play by means of a button.”

Immersed in the month that commemorates the Mexican Revolution and to “dignify the profession, as well as generate community”, the guild will officially deliver, on November 23, at the Teatro del Pueblo, the technical file, as well as the safeguarding project to begin the process of being integrated into the list of Intangible Heritage of Mexico City.

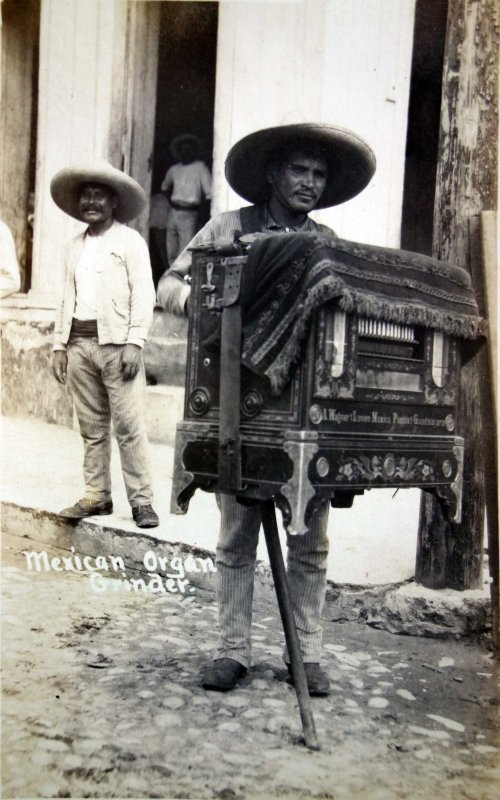

For more than a century, the barrel organ has been heard in streets, squares, parks, avenues, festivals and parades, becoming part of the soundscape of a Mexico that revived after the revolutionary movement.

The original instrument, weighing between 24 and 38 kilos, is a wooden box with an internal cylinder, metal pegs, and a crank that produces the mechanical music, two of its players explained to La Jornada. This barrel organ is carried by the so-called “cylinder players,” who travel to every corner, despite the weather conditions or the unpredictable and even chaotic events inherent to the capital city.

Victor Maya, who works near the Angel of Independence and is President of the Mexican Organ Grinders Cultural Corporation, warned: “Fake barrel organs are being mass-produced, sold, and placed on the streets, which is affecting this tradition, as well as the community of organ grinders who depend on this trade for their livelihood. We want to take action to counteract this practice, which is not readily apparent.”

The reality, Maya said, “is that there have always been fake barrel organs or recording devices; there are many in Puebla and Tlaxcala, but they were privately owned—someone had the idea, made one, and set it up somewhere. Now they’re being mass-produced and are very similar to the original barrel organs. The thing is, if someone walks past one, they might not realize it’s a recording they’re hearing, because the instrument has all the elements of a real one, like the fake wood carved like whistles, and other details. All they have to do is press a button, and the MP3-recorded music plays.”

A Plan to Safeguard Mexican Heritage

This problem, he added, “is detailed in the safeguarding plan, which includes a protocol for action from the organ grinder community with the institutions involved and specialists on the subject to reduce the presence of these objects in the streets.”

The process, which will begin on November 23rd in the context of the 91st anniversary of the Teatro del Pueblo, will involve submitting the technical file, the safeguarding plan, and the supporting documentation to the local Secretary of Culture. “After their approval, the same department will forward it to the heritage review committee on the 28th. On that day, we will have to present our project, and it will be voted on by the committee; if approved, it will be sent for publication in the local Official Gazette.”

If everything goes well, Maya explained that the group has defined three specific proposals. “One will be to create a cultural center in the city center, where the profession of organ grinder can be dignified, in addition to holding exhibitions and creating a professional development workshop focused on the conservation and repair of the instruments.”

Other objectives “are to create a center for the study of organ grinders at the Autonomous University of Mexico City (UNAM), where the history of the guild, which is extensive and closely related to mechanical music, will be documented, as well as to promote the third organ grinder festival, which will become international in scope and enter a circuit of specialized events around the world.”

Meanwhile, Román Dichi Lara, who also belongs to this group, commented: “Faced with technological changes and everything related to modernity, we have tried to survive; we have updated our repertoires, not with music that is popular now, but with music from 20 years ago, to remain relevant to people’s tastes. There are those who listen to us and it brings back memories of family members or other experiences from the past.”

He also pointed out: “But there are always people who try to take advantage, and there is a group of so-called organ grinders with boxes that simulate the instrument and have been fitted with an electronic speaker. This pre-recorded music is a deception of the public. They are not only affecting a tradition, but also harming numerous families who live and depend on this trade.”

The barrel organ “arrived in Mexico with Italian and German migrants” at the end of the 19th century, and its tradition has become an emblem of Mexican popular culture, especially in the capital city.

The street artists explained that the traditional monkey is also a key element of the craft, “which originated in Europe between the mid and late 1800s, especially in Italy and Germany, where families were accompanied by a small animal, usually a monkey.” Nowadays, of that once eye-catching monkey, only a doll in that shape, placed on top of the barrel organ, remains.

Regarding how many people are involved in this trade, Víctor Maya reiterated that there is no precise record. “The Historic Center Authority mapped the locations of traditional organ grinders, while the Labor Secretariat has around 350, but these are only those who have at some point applied for a license; beyond that, there is no more accurate data. We estimate that there are between 800 and 1,000 organ grinders in the country, including men, women, and young people.”

-

People’s Mañanera February 9

President Sheinbaum’s daily press conference, with comments on scholarships, return of mining concessions, PRIAN exposed, Bad Bunny Super Bowl, and aid to Cuba.

-

8 Million App Users, TV Soap Opera Ad… & the PAN Still Can’t Find New Members

In Mexico, where political parties are currently publicly financed, the right wing PAN has spent a staggering amount during its lackluster recruitment drive.

-

Mexico’s National Film Archives Workers Demand Dignity

“Our struggle is legitimate; we are not asking for privileges or luxuries, only better working conditions and job security. We also seek dialogue. This situation has become unsustainable.”