Under the National Security Strategy, Trump Pushes for Latin America’s Minerals, Energy & Infrastructure

This article by Aníbal García Fernández originally appeared in the January 10, 2026 edition of Revista Contralínea.

At the end of November 2025, as mandated by US legislation, the Donald Trump administration published the National Security Strategy (NSS), an important document that outlines the national interest of the elite in power, because, despite its decline, the United States continues to establish its global hegemony, increasingly through greater methods of coercion.

Unfortunately, the media, columnists, and a few analysts focused on the most sensational aspect: the Trump Corollary, instead of analyzing the true scope of this expansionist policy. By concentrating on this—which, moreover, is part of the US president’s strategy, imprinting his style and signature on his administrations—the trap lies in the fact that the conclusions say nothing about the true and dangerous objectives. For example, they end up stating: “return of the Monroe Doctrine,” “US revives the Monroe Doctrine,” “The return of the Monroe Doctrine in the 21st century.”

In 2023, the bicentennial of this doctrine was commemorated. It serves as a guiding principle for the manifest destiny of the US elite in the Americas, leaving behind colonialism, territorial dispossession, military interventionism with invasions and military bases, the acquisition of vast territories with their extensive strategic and critical mineral resources, and market dominance for US companies that establish monopolies over the most dynamic sectors of Latin American economies. This, in turn, allows for the extraction of surplus value through the exploitation of a highly skilled but low-wage Latin American and Caribbean working class. In short, it represents US possession of the continent, whether by military or commercial means. This is Nicholas Spykman’s vision in the 21st century. What else is the struggle for raw materials, the division of the world among powers, militarism and militarization, and the establishment of monopolies dominated by financial capital, if not imperialism?

Energy, Minerals & Infrastructure: the Power Struggle

As discussed previously, Southern Command had already made it clear in 2025 that Latin America and the Caribbean “are on the front lines of a decisive and urgent contest to define the future of our world.” The 2025 National Security Strategy confirms this and allows for an analysis of Trump’s actions this year.

For example, the National Security Strategy mentions that it will deny non-hemispheric competitors—such as China—”the ability to position forces or other threatening capabilities, or to possess or control strategically vital assets,” as well as “reconsider their military presence,” control maritime routes and thwart illegal migration, establish “targeted [military] deployments to secure the border and defeat cartels, including, when necessary, the use of lethal force.” And finally, expand access to strategically important locations.

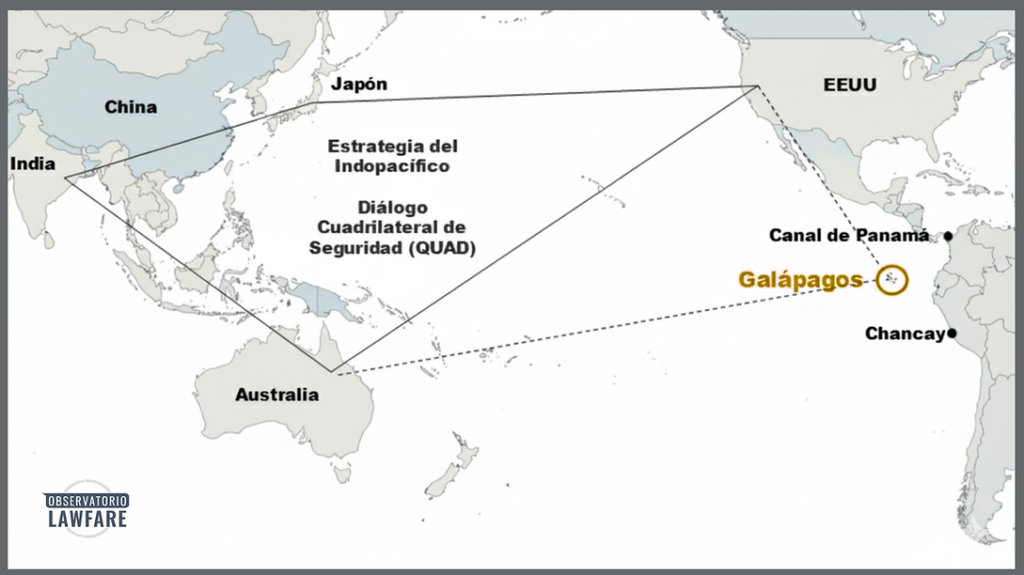

What does this imply? It means considering Greenland’s resources and Trump’s intentions to buy it (the imperial division of the world in the 21st century); it means remembering why there’s such interest in regaining control of the Panama Canal, which ultimately masks the fact that a Chinese company owns two ports at each end of the canal and that they tried to sell them to BlackRock’s enormous financial capital—which holds shares in pharmaceutical, energy, technology, and food companies; it means paying attention to “the key to empire,” that is, maritime control of the Caribbean, with its various tributaries between islands, but also the Galapagos Islands, which project imperial influence into the Pacific, with a view to containing China, as Dr. Tamara Lajtman mentioned to Contralínea.

At the heart of the dispute are minerals; this became clear at the G7 meeting [in Canada, in 2025] —which President Claudia Sheinbaum attended. Beyond the national security interests of the US elite, it is clear that the capital behind this strategy is primarily financial capital, as well as technological and fossil fuel capital.

The G7 meeting in 2025 established the following lines of action: “building energy security and accelerating the digital transition”, “strengthening supply chains for critical minerals”, “boosting the adoption of AI in the public and private sectors”.

The National Security Strategy shows that the Donald Trump administration – as in the first time – is strengthening spaces for private capital that will work in tandem with the Departments of State, War and Energy; the Small Business Administration; the International Development Finance Corporation – previously restructured by Trump in his first administration –; the Export-Import Bank, and the Millennium Challenge Corporation.

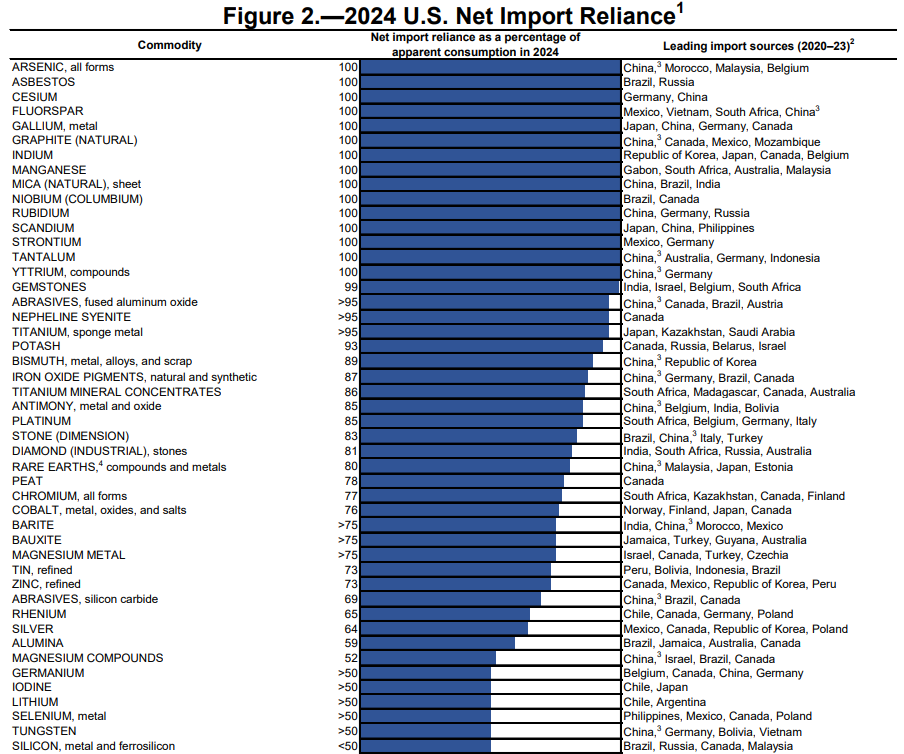

Which minerals are critical for the United States? To answer this, we need to look at the U.S. Geological Survey and understand its enormous mineral dependence on a dozen countries. These include China, Brazil, Russia, Mexico, Canada, South Africa, Germany, Australia, India, South Korea, Peru, Bolivia, and at least Chile.

Among the minerals on which it is 100% dependent are: arsenic, asbestos, cesium, fluorine, graphite, indium, manganese, mica, niobium, rubidium, scandium, strontium, tantalum, and yttrium. And a long list follows, reaching 50% dependence, where Brazil, Mexico, Chile, Canada, China, India, and South Africa continue to appear.

Thinking about that mineral dependence implies two aspects: control of the extraction-production-transformation chain and, therefore, of the trade routes; several of them, centered in the geopolitically relevant area that is the Indo-Pacific, in which the United States has had a security strategy since the first Trump administration, with clear security precedents with Australia.

On the other hand, it involves considering the industries that require these types of minerals. This is where the military-industrial complex and manufacturing come into play, as well as high technology, particularly focused on semiconductors, chips, and new renewable energy technologies. The latter has been an economic sector where the dispute with China has been intense since 2017, when the trade war between the two powers began. However, as the Financial Times suggests, trade relations for certain types of chips between the two countries are likely to be re-established, despite ongoing geopolitical conflicts with China over semiconductors, the automotive and military sectors, and, of course, the Taiwan factor.

Finally, there is energy and infrastructure. The National Security Strategy emphasizes the need to build a “scalable and resilient energy infrastructure, invest in access to critical minerals, and strengthen existing and future cyber communications networks that take full advantage of the U.S. encryption and security potential.”

In his first administration, Trump established the Energy Resource Governance Initiative (ERG) in 2019 and the Clean Grid Initiative in 2020 to exclude Chinese companies from 5G infrastructure. In 2025, the National Energy Strategy (NES) is revisiting this approach to strengthen the private sector’s presence in Latin America. This establishes a continuity between the last four US administrations, which, as Dr. Rocío Vargas suggests, have been characterized by a geostrategic repositioning of hegemony through energy, structuring a series of long-term strategies.

As we realized months ago, when reviewing Trump’s first hundred days, some of those strategies are: Connecting the Americas 2022, established since 2012; Energy Protection Strategy with Europe; EU-Caribbean Strategy 2020; Atlantic Cooperation 2024; and the AUKUS strategy, which protects the main maritime routes through which several strategic goods circulate, including oil and gas.

Therefore, it is extremely important to consider Trump’s actions in the Caribbean against Venezuela, which possesses the world’s largest oil and gas reserves; but also the energy importance of Brazil and, to a lesser extent, Colombia and Mexico. And of course, there is Argentina’s massive unconventional gas field, Vaca Muerta. This is why Latin America is at the center of international disputes, because no other region possesses these strategic resources.

But also because we are already facing an energy crisis : the world’s remaining oil and gas reserves are dwindling. The era of large oil wells and low prices per barrel is over, and there are now signs that the United States, which became the world’s leading oil and gas producer, is reaching peak oil. Furthermore, it is one of the world’s largest oil consumers and requires a secure supply of crude oil and gas to fuel its economy and industry.

Two more facts: The United States has the world’s leading energy infrastructure and gas pipeline network. Second, it’s crucial to note that Mexico is its main trading partner and primary market: we account for 30 percent of gas exports, according to data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration. This gas covered 74 percent of Mexico’s national demand in 2024. This gas is primarily used as a primary energy source to supply the national electricity grid.

Therefore, Mexico is facing a race against time to strengthen not only energy sovereignty, but also energy security, which implies at least considering affordability, economic accessibility, resilience, and physical availability, including both infrastructure and supply. In this context, it is crucial to recognize the importance of strengthening Pemex and CFE, companies that were dismantled during the neoliberal period and that still face adverse provisions under the USMCA, which will necessarily have to be reviewed in the treaty’s update, in light of the reforms to Articles 25, 27, and 28 of the Constitution.

And regarding infrastructure, it takes us back to 2019 and the BUILD Act, which was promoted by Trump to expel companies from other continents from the region, primarily Chinese, but also other Asian companies. The BUILD Act aimed to “modernize U.S. development finance capabilities,” and the institution chosen for this purpose was none other than the International Development Finance Corporation (OPIC). Therefore, we will see various OPIC projects in the areas of infrastructure, energy, and mining.

In 2021, the Joe Biden administration launched the “ Build Back Better World ” (B3W) initiative. It aimed to strengthen the United States’ multilateral presence with G-7 organizations, NATO, and others such as the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), to curb the advance of China and Russia in infrastructure projects, trade, and military power.

Now, Trump, in his National Security Strategy, mentions that agreements with countries that “depend on us” —including Mexico, and several Caribbean and Latin American nations— must include sole supplier contracts for our companies and that we must “do everything possible to expel foreign companies that build infrastructure in the region.” Clearly, this targets companies from China, Russia, and even, to a lesser extent, some European companies.

Such is the scale of the USMCA negotiations that Mayor Claudia Sheinbaum is facing. Are they negotiating the possibility of awarding “sole supplier” contracts to US companies under the USMCA? That will become clear in 2026. We will also find out if the US government manages to achieve this objective in the countries with which it has trade agreements, including Mexico, Colombia, El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and the Dominican Republic. And there is the possibility of a trade agreement with Argentina and perhaps Ecuador.

Military sales, another area of US interest that has demonstrated its power, will be analyzed on another occasion. This is exemplified by Argentina, which purchased obsolete aircraft for millions of dollars. However, countries like Colombia and Mexico have reduced their purchases from US companies.

In the case of our country, as was made clear by the now War Department in the midst of the pandemic in 2020: “ the most serious impacts for the Department of Defense of Covid-19 related industrial shutdowns at the national level are in the aviation supply chain, shipbuilding and small space launch […] in a Pentagon press conference, Ellen M Lord said that internationally, several hotspots of industrial base closures are affecting the Department of Defense, particularly in Mexico.”

It must be made clear the strategic place that Mexico has in the US military-industrial complex, as well as in financial capital, another element of power highlighted by the new ESN 2025.

From Monroe To Trump

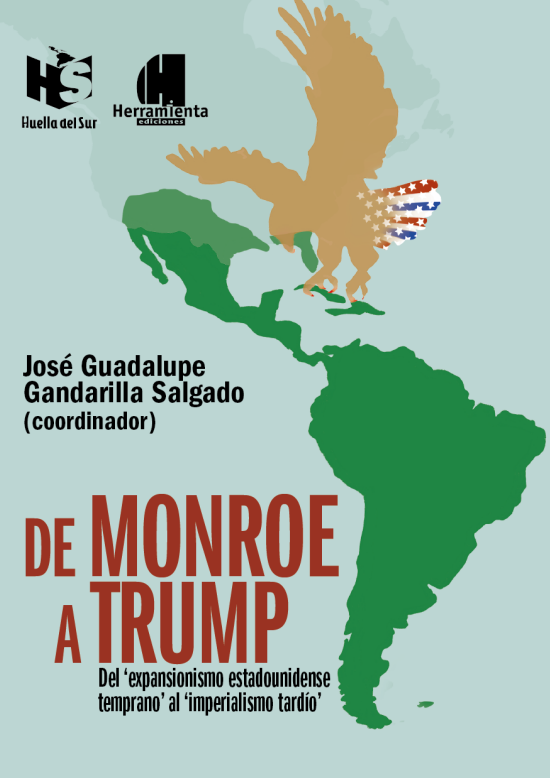

Two years ago at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), an international seminar led to the publication of a book that arrives at a crucial moment: From Monroe to Trump: From Early US Expansionism to Late Imperialism, coordinated by Dr. José Guadalupe Gandarilla. The text comprises nine chapters that demonstrate precisely the opposite of what several Latin American newspapers have headlined: the Monroe Doctrine never disappeared and is more alive than ever, despite Democratic and Republican administrations. Of course, the logical question is: if it never disappeared, has it always been the same, or have there been changes?

As Silvina Romano, Tamara Lajtman, and Marcelo Maisonnave point out , there is a key change: “it diminishes the importance assigned to the Middle East and stops placing China as the main threat. The bad news is that it shifts its focus to the Western Hemisphere [Latin America and the Caribbean], explicitly returning to the premises of the Monroe Doctrine and the Roosevelt Corollary.”

Such is the scale of this intensified imperialism, and, dialectically, such is the magnitude of its hegemonic decline, in which, through military presence, economic sanctions, and soft power wielded through alliances with right-wing groups and political puppets, it attempts to control what, in theory, was meant to be the new American century. This is summarized in the phrase found in the National Security Strategy 2025 itself: “ The days when the United States propped up the world order like Atlas are over .

-

Sheinbaum: Rejection of Electoral Reform Not a Defeat, Will Present Plan B

Reforms include capping the resources allocated to local deputies & municipal councilors; expanding public consultations to include political party budgets; and holding recall elections in the third or fourth year of the Presidential term.

-

What Does President Sheinbaum’s New Housing Initiative Propose?

The Executive branch seeks to incorporate the concept of adequate housing into public programs, considering not only the physical characteristics, but urban environment, availability of services & accessibility to development.

-

40-hour Workweek: A Handout from Employers That Won’t Improve Workers’ Lives

With the 40-hour workweek reform, if a worker were to work the 36 extra hours per month at double pay, they would only receive 1,206 pesos more per month than they would under the previous mandatory 48-hour workweek.