Our Water, In Whose Hands?

This article by Elena Burns originally appeared in the January 15, 2026 edition of Revista Contralínea. The views expressed in this article are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect those of Mexico Solidarity Media or the Mexico Solidarity Project.

Last December 2025, in a brutally top-down process, the Executive and Legislative branches perpetuated the slightly modified Salinas-era National Water Law (LAN) and masked the constitutional violation with a hollow General Water Law (LGA). Therefore, we, the members of the National Coordinating Committee for Agua para Todos—communities, researchers, and citizens with 13 years dedicated to establishing a General Water Law focused on sustainability, equity, and participation—analyzed what happened.

After holding numerous forums and workshops, collecting 200,000 signatures with voter ID cards, working with five legislatures, and, in my case, serving at the National Water Commission (CONAGUA) with the instruction “water is for the people, not for special interests,” this experience of imposition and pretense, which occurred on January 3rd, left us with many questions: Why did they decide to reinforce water authoritarianism, leaving the hydrocracy in the only spaces for participation? Why the rush? Why did the President’s vision regarding water management change so radically? And how are we going to defend our water sovereignty in this new continental scenario?

To analyze what happened, we begin with the only real change in the approved legislative package: the establishment of the Water Reserve Fund, an instrument that will be managed by CONAGUA (the National Water Commission) to obtain allocated volumes for “reassignment.” It was announced that, by replacing transmissions with reallocations from the Fund, the State will substitute the market to end the commodification of water and guarantee the human right to this vital resource.

However, in order for the Fund to meet these objectives, the following questions must be addressed: where will the concessioned volumes come from; how will the over-concessioning, hoarding and dispossession inherited from LAN’s 33 years be dealt with; to whom will the obtained volumes be dedicated; and, how will these decisions be made?

Mexico’s new “National Strategy” for water aims to fulfill the human right to water and sanitation… in 60 years.

From Agua para Todas, after losing the fight to replace the Salinas-era law with a single General Water Law for integrated and participatory management, we prepared a document in the “says-should say” format proposing the essential minimum adjustments to the Executive’s package, paying close attention to the Fund. We decided to go for everything, but not to be left with nothing.

Despite the strict instructions from CONAGUA and the Speaker of the House to approve the Executive’s initiative immediately and without discussion, we obtained the support of the Water Resources Commission to organize 16 open parliaments, mainly in conjunction with the local Congresses.

Furthermore, along with other like-minded actors, we presented over 450 papers at the public hearings organized by the Commission and sent more than 121,300 letters to our federal legislators. However, just as the Director General of CONAGUA, Efraín Morales López, had ordered from the outset: “They won’t change a single thing,” and so it was; the rejection was absolute. Only the tractor drivers from the north managed to secure some clarifications to the original project.

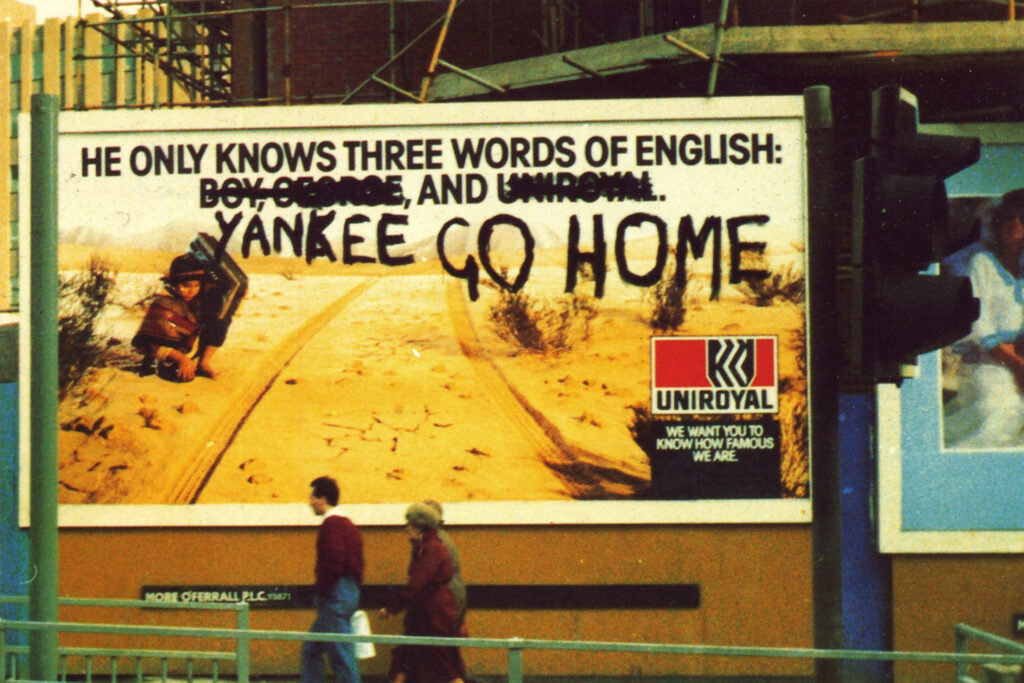

To analyze the intention behind the “Water Reserve Fund,” we recall that the National Water Law was one of four laws (including the forestry, mining, and agricultural laws), along with the counter-reform to Article 27 of the Constitution, enacted in 1992 as a condition for signing the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). The version of subordinate integration established by NAFTA required weakening the nation’s sovereignty over our lands and waters, a sovereignty established by the Mexican Revolution, in order to replace the State with the free market.

Now, under “Subordinate Integration 2.0,” the Mexican state is openly assuming the role it has always played under neoliberalism: facilitating access to natural resources for special interests. In this new version, not only do transnational corporations demand access, but the neighboring state has declared it will seize resources by force. Along the same lines, the Mexican state is committing to providing the water requested by the thirsty artificial intelligence data centers, mining operations, fracking projects, and nearshoring industrial parks , all of which seek to locate in areas already over-concessioned.

The design and operation of the Water Reserve Fund was an essential point in our attempt to replace the concession market with the consensual and sustainable management of basins and aquifers, as well as the recognition of the rights of water-marginalized populations.

We proposed that, instead of the Fund, reserve funds be formed by basin or aquifer that obtain their water through the recovery of the volumes granted for industrial and service use, for which their holders have not paid rights, 3.5 billion cubic meters (m3) in 2023, 80 percent of the total for these uses1.

We also insisted that broadly representative regional councils register the volumes required to respect the water rights of community systems, Indigenous peoples, and agrarian communities, and that they agree on reductions in non-essential uses to eliminate over-extraction. We further proposed allowing public oversight of reserve funds; these proposals were flatly rejected.

Under the decree published on December 11, 2025, the Reserve Fund will obtain its water rights through the expiration of rights that have lapsed or have not been used for two consecutive years (Article 29.3). These mechanisms have historically been used to extinguish the rights of ejidos (communal landholdings) and other small agricultural users who have failed to request extensions more than six months in advance, or who, due to economic or climatic reasons, have been unable to demonstrate the use of their concessions for two years. The approved project reduces the window for requesting extensions from 4.5 years to 2.5 years; the original version allowed only six months.

Those of us who have spent decades striving to build good water governance find ourselves facing a water authority that is as distant, opaque, and arbitrary as ever, extremely vulnerable to pressure from special interests. But now, faced with threats from the north, more than ever we need the government to open up and coordinate with the people for the defense and proper management of water, the foundation of life in every corner of the country.

At the same time, the revocation of concessions for non-payment of fees (Article 29.4) remains discretionary, and revocations are exempt from being contributed to the Fund (Article 37.1). The Fund must prioritize concessions that contribute to the human right to water, food security, or national development (the first version did not specify priorities). An inter-ministerial committee headed by CONAGUA will review the reassignments. The structure and operation of the Fund will be determined by regulations drafted by CONAGUA itself, without the obligation to ensure public access.

Other fights we lost in this big round include:

- The government refused to eliminate the chapter that “promotes and encourages” private participation in the financing, construction and operation of federal hydraulic infrastructure, as well as in the provision of the respective services, a chapter that has resulted in costly disasters such as the El Zapotillo dam, the El Realito aqueduct and the Atotonilco wastewater treatment plant (WWTP).

- They refused to incorporate into the LGA the language of the Mexico City Constitution that prohibits the privatization of water and sanitation services, leaving the country vulnerable to the unfavorable and impossible-to-cancel arrangements that are being suffered in Puebla, Quintana Roo, Saltillo, the Port of Veracruz, among others.

- They refused to demand that national waters allocated for urban public use respect the human right to water, and that public resources prioritize the efficiency of hydraulic and sanitation systems to reduce dependence on water transfers.

- Instead of our proposal for a National Program of immediate actions, their “National Strategy” aims to fulfill the human right to water and sanitation in six 10-year periods.

- They rejected the proposal to build broadly representative Regional and Local Councils for the planned management of basins and aquifers to influence concession patterns, reaffirming instead the bodies controlled by large water concessionaires.

- They rejected our proposals to democratize and eliminate corruption in irrigation districts, which hold 33 percent of the total volume of water allocated, and which are being captured by dark forces.

- They refused to guarantee the water rights of community systems, agrarian communities, and Indigenous peoples.

- They refused to include provisions for community systems to have access to the urban public use rate (to which real estate companies have access) instead of having to pay the industrial rate, which costs 36 times more (Article 223, LFD).

- Instead of eliminating the “guarantee quotas” essential for speculation, they extended them to six years, unlike the current two; in addition, they recognize “reassignment” (read: authorized purchase and sale) as a right of the concessionaires.

- They rejected our proposals to replace “may” with “shall” in the LAN, to eliminate discretion and force CONAGUA to inspect, sanction and correct over-concession and fiscal impunity.

- They rejected our proposals that would mandate the use of cutting-edge technologies and citizen participation to eliminate corruption in the calculation of available resources, as well as inefficiency in inspections.

- They determined that the “human right to sanitation” only refers to the removal of excreta from wastewater.

- They eliminated the immediate closure of an industrial use when illegal discharges were documented during an inspection and refused to include water pollution in their new chapter classifying crimes against national waters.

Upon completing this regressive project, the legislators and the Executive branch effusively congratulated themselves on having achieved “a new legal framework for water.” For those of us who experienced the process firsthand, the celebration left us cold. In the open parliaments, we heard the testimonies of Indigenous and rural communities who continue to suffer from corruption and mistreatment at the hands of the National Water Commission (CONAGUA).

We found it impossible to believe that “now they are going to bring order to the concessions,” when our repeated attempts to support CONAGUA with information gathered in the field and by satellite platforms have been rejected, and our requests for transparency regarding the announced progress have been denied.

Those of us who have spent decades striving to build good water governance find ourselves facing a “water authority” that is as distant, opaque, and arbitrary as ever, extremely vulnerable to pressure from special interests. But now, faced with threats from the north, more than ever we need the government to open up and coordinate with the people for the defense and proper management of water, the foundation of life in every corner of the country.

Elena Burns is a Member of the National Coordinating Committee for Water for All, Water for Life, and of the National Autonomous Water Comptroller’s Office; former Deputy Director of Water Administration at CONAGUA.

- Burns, E. “¿El agua paga el agua?”, El Economista, 23/07/2024 ↩︎

-

People’s Mañanera March 6

President Sheinbaum’s daily press conference, with comments on Jalisco security strategy, World Cup security, electoral reform and USMCA review.

-

Experts Warn About Excessive Overtime with Reduced Working Hours

The increase in permitted overtime hours may be seen by companies as a permanent remedy to compensate for the reduction to a 40-hour workweek.

-

US Imperialism & Zionism Are the Enemies of Humanity

As the liberators of our America taught us, from Bolívar to Martí, and as Commanders Fidel Castro and Hugo Chávez reminded us in their unwavering struggle, the unity of the people is the only force capable of confronting & defeating imperialism.