SOCIALISM: DIGNITY WITHOUT PAPERS

Doctors were concerned about the eyesight of prisoners and hostages being released in Israel/Gaza, fearing that when they emerged from the shadows after a long incarceration, the sunlight could damage their eyes.

For immigrants in the US living without documentation, it’s also much like living underground, imprisoned in a cage of fear. All they have is gone, including their human dignity. Luisa Martinez tells us what that was like for a young woman desperately wanting to make something better of her life.

She says that when she finally got her work permit, it was as valuable to her as a gold nugget, a ticket to the upper world where the sun shines.

The freedom to move not only benefits the migrant; it benefits the place where they land. Nowhere is that more true than the US — its economic success has relied on the constant infusion of new workers from around the world. As Alex González Ormerod, editor of The Mexico Political Economist, said in a recent interview about the migrant crisis, “The crisis isn’t because they’re coming, the crisis is because you’ve criminalized them.”

My Chinese migrant ancestors during the 1840s gold rush called San Francisco “jinshan,” golden mountain. But by 1882, Chinese were legally banned from entry, while European migrants entered freely — showing that the issue is not migration itself. After 1882, the Chinese “illegals” had to find ways around the law, including pretending to be Mexicans and coming across what was then an open southern border!

US leaders whose ancestors may have come out of the shadows are now blinded by the light. They ignore the role newcomers have played in making the US “great.” As in Mexico, migrants should be recognized as “heroes,” not branded as criminals.

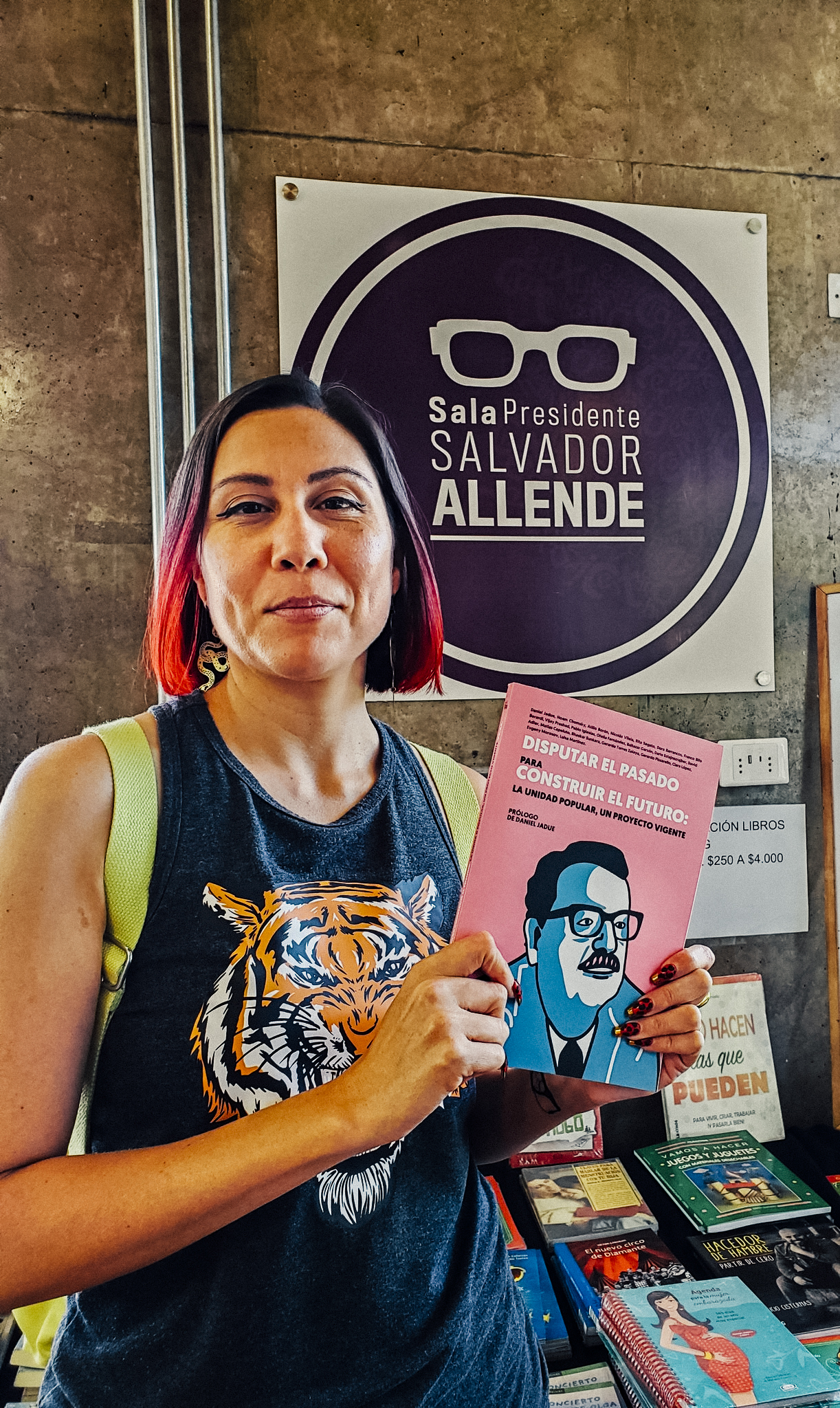

Luisa Martinez has been a community and socialist activist for fifteen years, particularly focused on immigrant justice in organizations like the Florida Immigrant Coalition. She is a member of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) International Migrants Rights Working Group, its International Committee and an elected leader on the DSA National Political Committee.

You became a tireless organizer for immigrant rights with a passion that grew from your own experience. Can you speak about the psychological effects of living without papers?

Yes. I like to explain it by comparing clinical depression and situational depression. In my mid-twenties, I was diagnosed with major depressive disorder. My university-provided psychiatrist said clinical depression was not about feeling sad but about feeling a paralyzing sense of hopelessness. My future seemed hopeless — I was in danger of flunking out of school. Not graduating from college, I thought at the time, meant continuing the cycle of poverty I was born into and never achieving the emotional and material stability we all crave.

Not having documents was another type of depression. It may have been situational, but it didn’t feel any different from clinical depression. As a second-class person, I had no hope for the future. I couldn’t get a regular job without a Social Security number; my jobs were “under the table” and exactly the jobs you’d imagine. My bosses often stole my wages, and I was sexually harassed. Both these crimes happened again after I got my legal papers — but without papers, complaining was never an option.

It’s illegal to drive without a license. I had to take three buses to work, two of which ran only once an hour. At my job as a prep cook and dishwasher, I had to get to the bus stop by 7:30 am to arrive at work by 10 am. After my shift, I took two more buses to my second job at another restaurant and worked till 10 pm.

South Florida’s transportation system is unreliable — sometimes the bus didn’t come. My pay was a whopping $6 per hour. Once, I ran out of money halfway to work and remember sitting utterly defeated outside a Publix supermarket asking people for change. I had no access to a bank account and could only carry cash. A kind woman gave me a couple dollars, and I made it to work.

I made friends with one of the bus drivers, a friendly Mexican guy. One day, some biker-looking guys got on the bus and started saying racist things to us: “Mexicans are cockroaches! Go home!” I am Chilean, not Mexican, but that didn’t matter to them. My bus driver friend intentionally drove past their bus stop and left them standing there while yelling at them, “Viva México!” I was so in awe that he refused to take their shit!

I couldn’t go to college, and that was the worst thing. When I tried to apply to community college, the nice woman in the office told me that because the 2001 plane hijackers had used tourist visas to apply to flight school, they no longer permitted people on expired tourist visas to enroll. She suggested that I enroll as an international student — at fees five times higher! Without legal status, of course I had no access to financial aid. On my $6 an hour, she may as well have said it cost a million dollars per semester.

How did you gain legal status?

At rare moments in US history, the door opens briefly. In one such moment, President Ronald Reagan declared an amnesty and passed the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA). My grandfather eventually got his green card through IRCA. Once granted, he could sponsor my mother and me under a family-based visa. But the process is long, complex and expensive. It took 18 years for my mother and me to receive work permits.

But eventually, one hot, sunny day in July, I received the permit in the mail. I shut the door to the only room in our apartment and cried. Finally — I could get a job, go to college, get a driver’s license without fear. It felt like the permit was made of gold!

What were the psychological effects of hearing others use the term “illegal?”

Because I heard the word “illegal” used as a noun throughout my whole life — not followed by the noun “immigrant” — I internalized the idea that my very existence was illegal, not just my immigration status.

One time, in my teens, I was visiting a white friend and casually mentioned that I wasn’t born here. I thought it was fine to mention because she was my friend. Her grandmother was in the room. Her eyes got wide; she pointed at me and said, “You’re illegal!” I felt my heart drop into my stomach but didn’t say anything back. My friend tried to laugh it off and change the subject, but I was terrified. I never went to her house again and vowed never to mention where I was born to white people. I felt it was a shameful secret to be Latin American.

What ultimately made you gain your sense of dignity?

I didn’t discover what real dignity was until I became a socialist years later. After I got my paperwork, I enrolled in college right away and eventually made my way to the University of Florida.

I read Noam Chomsky’s Latin America: From Colonization to Globalization and finally learned why so many Latin Americans have to live in the United States — because of generations of Western repression, forced handover of natural resources, and counterrevolution. My perspective evolved as I learned about Latin American struggles against Western imperialism — and unlearned falsehoods about our own revolutions.

Most importantly, I learned to turn shame into pride. Puerto Rican journalist Juan Gonzalez said, “those of us from the Global South come to the US to reclaim our share of the resources that have been stolen from our home countries by the Global North.” It was a huge breakthrough! I wasn’t here to take anything away from US citizens; I was here to get what was unavailable to me under the US-imposed Chilean dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet.

That was the moment the anger in my heart grew bigger than my fear of the US government or La Migra. That was the moment I started to feel dignity. I could fight back, like my Mexican bus driver friend. But my method would be community organizing.

Is a socialist perspective essential to solving the immigration issue?

In the DSA and among other leftists, I sometimes see hesitation, particularly from our white comrades, about getting involved in immigrant rights work. But socialists should be leading the opposition to mass deportations in a way that advances our broader demands as socialists, rather than leaving the work to the non-profits.

The difference between kind, well-intentioned NGO employees beholden to their wealthy financial donors and us is that we critique the capitalist system, which exploits undocumented workers, blames them for social problems and creates divisions among workers based on race and legal status. Without socialism — a government of the workers, for the workers, and by the workers — oppression will continue.

Socialism gives me hope. A socialist vision that ends all illegal, murderous sanctions against countries like Cuba and Venezuela; a socialism that ends all US-backed wars, military occupations, coercive trade agreements and the climate changes that drive human displacement; a socialism that declares if capital can move across borders, so can we.

We can declare socialism as an alternative to Trump’s hateful rhetoric.