CUT & RUN GARMENTS

The United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, or USMCA, the trade agreement that followed NAFTA, will be renegotiated in 2026. To help us understand the issues at stake, we are printing part of Jeffrey Hermanson’s interview explaining the history of free trade and the maquiladoras. The following piece has been excerpted from his interview with Andrew Ekrod and edited for length and clarity. The complete interview can be read at Phenomenal World.

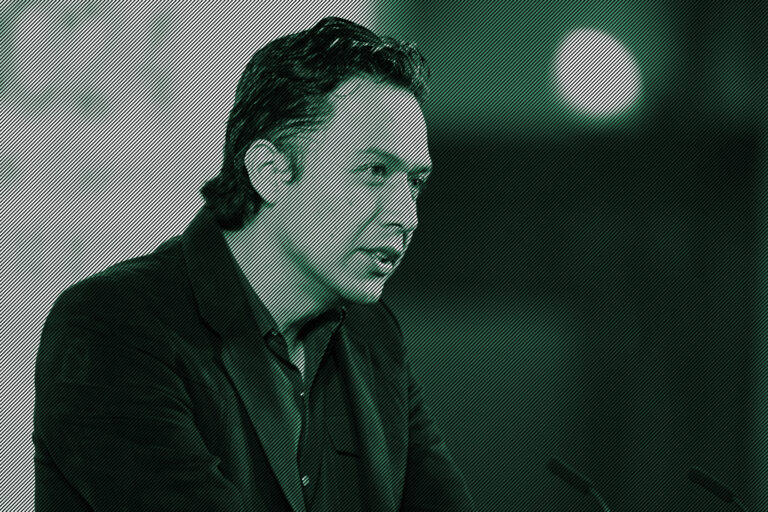

Jeffery Hermanson began his career with the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) during the late 1970s. He traced the migration of the textile industry after the passage of NAFTA to Mexico and elsewhere, which led him to a lifetime of organizing workers across national boundaries. He has lived primarily in Mexico since 2019, when the AFL-CIO Solidarity Center appointed him Director of Organizing in Mexico. He retired in 2022.

Maquila means mill, and maquiladoras were factories built in the 1980s near the Mexico-US border, with the companies’ most labor-intensive work subcontracted to them. The US shipped unfinished goods across the border; the products were finished in Mexico and then shipped back to be sold.

These enterprises became large, well-capitalized factories in the early years of NAFTA, and workers from all over Mexico came for the jobs and settled into poor communities they built themselves.

A few years after NAFTA was passed in 1994, I visited one of these “free trade zones,” or industrial park areas, and saw terribly poor conditions, with wages insufficient for supporting human life. Workers built houses out of pallets. There was even a song, “Casas de Carton,” about Mexicans living in cardboard shacks. They got their electricity from homemade attachments to overhead electricity lines with wires all over the ground running into the houses. The dirt streets turned to mud when it rained.

Manufacturers were encouraged to move to Mexico due to a particular tax arrangement, put in place by neoliberal politicians, that attracted direct foreign investment. Investors were offered lighter taxation and special deals with local authorities for land and other utilities, especially water. Before AMLO’s government in 2018, foreign companies often got free land and paid no taxes on land or buildings for ten years, robbing local communities of needed resources.

But what we call runaway shops had developed well before NAFTA. During the 50s and 60s, employers were running away from the Northeast and Midwest to the US South and Puerto Rico, where workers were less unionized and had much lower wages. In garment manufacturing, where I began organizing for the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, or ILGWU, the core of the US industry was in New York City, Philadelphia, Chicago. But in the 50s, the jobs started moving south.

In 1965, the Congress passed a law, part of the US Tariff Schedule, that permitted garment manufacturers to cut goods in the US and send the pieces to the Dominican Republic and other Caribbean sites to be sewn together and exported back to the US duty free. By the late 80s, a couple of hundred thousand workers were sewing apparel in these free trade zones for the US market.

In the 70s and 80s, companies like Maidenform, Fruit of the Loom and Hanes moved to Puerto Rico and then primarily to Honduras and El Salvador.

On the southern border with Mexico, the garment industry followed the same pattern. Prior to NAFTA, the twin-plant system had a cutting factory on one side of the border and a sewing factory on the other. For example, workers cut Calvin Klein jeans in a union shop in El Paso, Texas, and then they were sent to Durango and Coahuila in Mexico for sewing together, and then finally imported back to the US. But after NAFTA took effect, garments were no longer cut in the US, and those jobs were eliminated.

Have things changed with the Morena government after 2018? They did establish tax rates that are equal to what Mexican companies pay and are requiring maquiladoras, more and more, to abide by the same regulatory requirements.

Yet, we still see favorable treatment for big investors. Nestlé, for example, just announced a $400 million investment in Chiapas with very favorable terms for water use. Here in my local community, a maquiladora is making sweatshirts and hoodies for Fanatics and Columbia Sportswear, which also has a special contract for water use. Water is scarce and at a premium in this area, but they get a relatively good price and use it to dye and launder garments.

By looking at one labor sector, the garment industry, we see how runaway shops took away US jobs, exploited Mexican workers and impoverished the communities they live in.

-

“Clueless” Morena Governments Signed Privatization Agreement: Marx Arriaga

“Just because the government or its leaders are from Morena doesn’t mean that all institutions have a progressive vision,” the Director General of Educational Materials commented.

-

Taibo II: Suppressing Self Criticism in 4th Transformation More Dangerous Than a Rupture

In an interview, the writer and Morena founder emphasized the pursuit of unity at all costs can be counterproductive, as it hinders the purging of those who replicate the practices of “old politics.”

-

Because Women’s Bodies Belong to Women

An interview with human rights defender, union organizer, & educator Fabiola Paulina Ramírez Ortiz, founder of Mariposas Mirabal.