Wrangler Mexico & Surplus Value Extraction

This article by Renata Aguilar originally appeared in the September 22, 2025 edition of Informador Obrero.

Andrea has been working at Wrangler in Coahuila for eight months. She hoped for job security to ensure the well-being of her daughters, but that won’t be possible. Her job will end on September 13th, the day the company will close its operations. In the meantime, she continues her normal work, which consists of sewing the pockets for pants. She does this work on two machines at the same time: one on her left and one on her right, which is very tiring, since Andrea remains standing throughout the workday and must remain focused to avoid accidents. She told Informador Obrero:

“I have to finish both sides within the established timeframes for one. It takes between 10 and 12 minutes to finish a bundle with approximately 60 pieces. So we make 120 pieces in the same amount of time because we work on two machines. I end up with swollen feet, numb arms, and overly tired.”

Andrea is a single mother of three daughters, ages 10, 14, and 15, whose basic needs she must meet. Although precarious, the salary she earns from Wrangler allows her to cover some of them, so the company’s closure has left her dismayed:

“As a mother, what am I going to do? Where am I going to find work with benefits? Pregnant women also work here, and they’re going to have a harder time; their maternity leave was scheduled for September and October,” she laments.

The value of a single pair of Wranglers is equivalent to four to six days of a worker’s wages, while they produce thousands of garments in an eight-hour work day.

José, another worker, shares his uncertainty: “I’ve been working for over twenty years; I made my life here. I don’t know what I’ll do next, but because of my age, I’m not accepted anywhere.”

The closure of Wrangler and the impact it will have on workers like Andrea and José are not isolated cases. They are part of the logic of global capitalism: relocating companies to reduce costs, extract more surplus value, and revitalize the profit rate, even if this means leaving thousands of workers unemployed.

Surplus Value Extraction In Accordance with the World Order

Dr. Mateo Crossa, a researcher at the Mora Institute, in his book Honduras: Maquilando Subdesarrollo en la Mundialización (Honduras: Maquilando Underdevelopment in Globalization), points out three stages of the internationalization of the textile industry.

First stage (1940-1960). Production moved to Asia, with a politically motivated counterinsurgency in the context of the Cold War and the triumph of the Chinese Revolution.

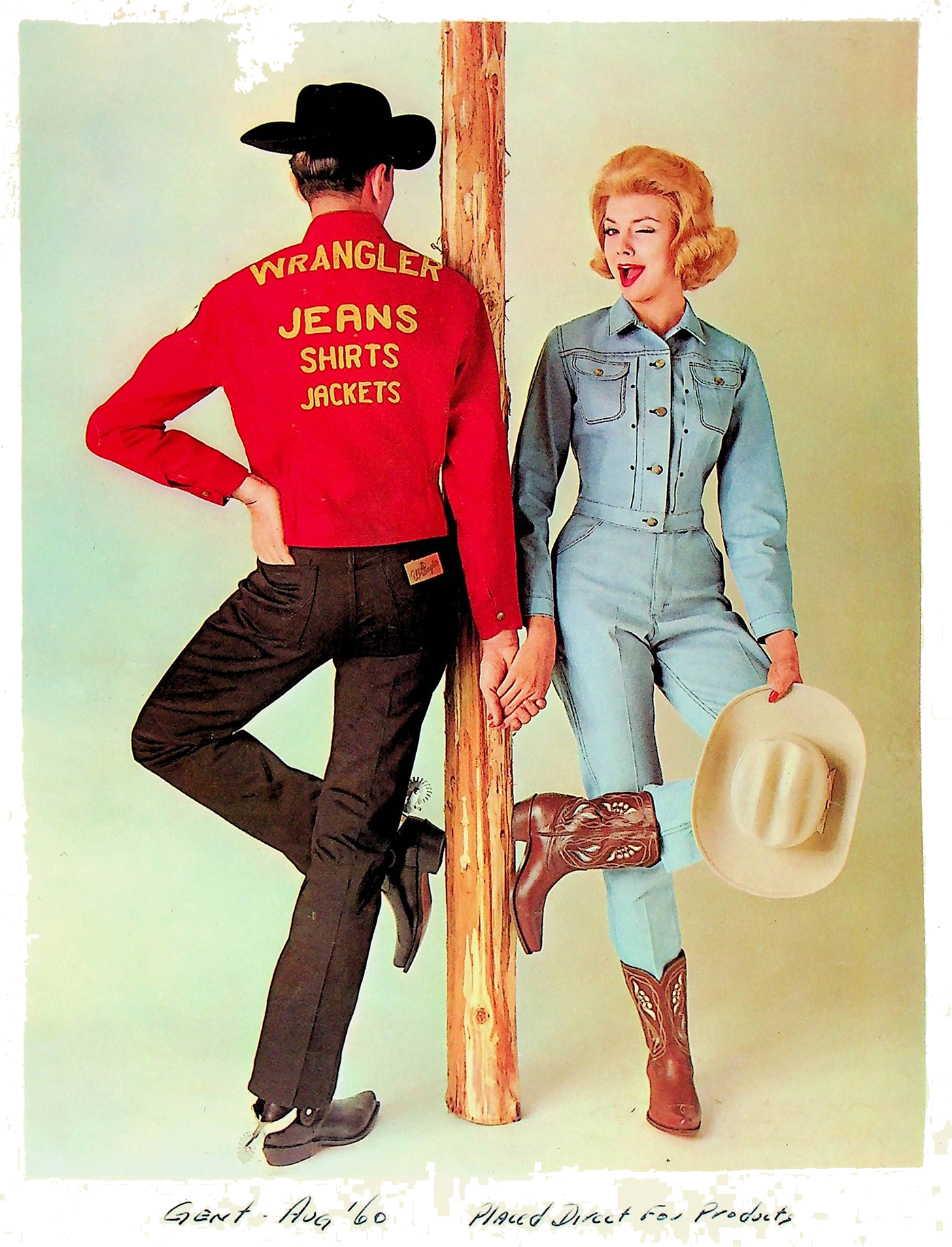

Second stage (1960-2001). Production moved to underdeveloped countries and was strengthened by free trade agreements. In Honduras, with the Caribbean Basin Initiative in 1984, and in Mexico, with the Free Trade Agreement in 1994. In this second stage, Inditex (Zara, 1992), Wrangler (1996), Nien Hsing (Levi Strauss and Co., Abercrombie, 1998), Mex Mode (Nike, Timberland, 1999), and Delta Apparel Inc. (1999), among others, arrived in Mexico.

Third stage (2001 to present). This coincides with a slower pace of growth in our country and a decrease in its contribution to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), falling from 131.395 billion pesos in that year to 115.75 billion pesos in 2019. In 2020, the situation worsened due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2023, the GDP of the textile and clothing industry decreased by 8.4 percent, according to information from INEGI (National Institute of Statistics and Geography, 2024).

Currently, in 2024 and throughout 2025, we have witnessed disruptions on the global stage, such as the tariff policies of US President Donald Trump, and, in Mexico, the passivity and submission of our government to these policies.

This third stage is characterized by increased exploitation in the garment industry, which still has not substantially automated its labor processes. This is due to the staff cuts in 2024 and 2025 of some companies that arrived in our country in the second stage and the closure of others, such as Wrangler.

Unlike textile production, where there was widespread automation of production processes, the same did not occur in the clothing industry, so productivity increased at the cost of the super-exploitation of workers in underdeveloped countries.

The relocation of companies at these stages naturally resulted in the deindustrialization of the United States, which ceased to create domestic value; and, on the other hand, the plundering of surplus value from workers in peripheral countries. As Crossa rightly points out, although value is produced in Mexico and Central America, it is realized in the United States and Europe, where the final products are consumed.

This is highly relevant because the replacement of the workforce in dependent countries is not necessary for capital to complete its valorization cycle, leaving workers vulnerable to greater job insecurity.

For all of the above, we cannot view what is happening in Wrangler as an isolated incident: the wages, labor rights, and living conditions of millions of Latin American workers are subordinated to this logic of global capitalism.

Wrangler in Coahuila

In Coahuila, Wrangler has four plants located in Torreón, Coyote, La Rosita, and San Pedro, employing more than 2,000 workers. The brand arrived in the northern state in 1996, during what was dubbed the second wave of corporate relocation, and after nearly three decades of extracting surplus value from Coahuila workers, it is rumored to be moving to Bangladesh.

There is no union advocating for workers in the face of the closure. The Revolutionary Confederation of Workers and Peasants (CROC), which previously administered the Collective Bargaining Agreement, didn’t even legitimize it. The union’s abandonment in the face of these phenomena is evident.

On the other hand, the government announced that it would set up support centers in conjunction with the company to provide legal advice to workers and mediate any grievances. They also reported that the Ministry of Labor and Social Welfare would organize job fairs to facilitate the workers’ reintegration into the workforce. However, so far, that has not happened, and the company’s closure is imminent. José tells us: “No agency has advised us, and so far, there hasn’t been a single job fair. We’re all ignorant here; we don’t even know how much, legally, we should be receiving in severance pay.”

The workers’ wages are 288 pesos a day. This is a stark contrast to the consortium’s profits and the price of the products they make: a pair of Wrangler pants sells for between 1,000 and 1,800 pesos in department stores in Mexico. The value of a single pair of pants is equivalent to four to six days of a worker’s wages, while they produce thousands of garments in just an eight-hour day.

Kontoor Brands (Wrangler)

Kontoor Brands, a US-owned company, is part of the global denim oligopoly. It includes Wrangler, Lee, Vans and, since 2025, Helly Hansen. The group is a giant in the textile sector. Its shares are listed on the stock exchange, which in 2024 had a total value of approximately $3.3 billion. In the second quarter of 2025, it reported total revenue of $650 million, far exceeding profit forecasts. The acquisition of Helly Hansen alone is estimated to generate between $425 and $455 million.

The company ranks sixth among its peers in the apparel manufacturing sector. Meanwhile, Andrea, José, and thousands of other workers will face unemployment and uncertainty.

Mexico in the New Crisis of Capital

Wrangler’s closure is just one link in a long chain. So far in 2025, at least 13 maquiladora and manufacturing companies have announced their departure from the country, most of them related to apparel manufacturing.

The impact is clear: rising unemployment swells the reserve army, that is, a portion of the population that is permanently unemployed, and which helps maintain precarious working conditions. Economist Ollin Vázquez, in Buzos de la noticia, notes: “This reserve army numbers approximately 45.5 million people. This precarious labor force exerts downward pressure on wages, a situation aggravated by the co-optation of labor defense mechanisms (such as unions) by interests alien to the working class.”

In other words, constant unemployment allows employers to offer minimal, precarious working conditions. Workers accept them because, otherwise, they would be replaced by others who also need work.

Thus, the deterioration of working conditions is widespread. We’ve documented it in Tamaulipas with Nien Hsing , in San Luis Potosí with General Motors, and we’re seeing it today in Coahuila with Wrangler. Everything indicates that this situation will continue.

Wrangler workers, Mexican workers, Latin American workers: we all face the same enemy: big capital. Only by raising workers’ awareness of their class situation, by organizing and unifying them, can we not only stop the super-exploitation to which we are exposed, but also shift toward a more just and humane economic model. A socialist economic model.

-

People’s Mañanera February 9

President Sheinbaum’s daily press conference, with comments on scholarships, return of mining concessions, PRIAN exposed, Bad Bunny Super Bowl, and aid to Cuba.

-

8 Million App Users, TV Soap Opera Ad… & the PAN Still Can’t Find New Members

In Mexico, where political parties are currently publicly financed, the right wing PAN has spent a staggering amount during its lackluster recruitment drive.

-

Mexico’s National Film Archives Workers Demand Dignity

“Our struggle is legitimate; we are not asking for privileges or luxuries, only better working conditions and job security. We also seek dialogue. This situation has become unsustainable.”