A Mexican Steel Company Died… Workers Followed

This article by Quitzé Fernández originally appeared in the November 30, 2025 edition of El Sol de la Laguna.

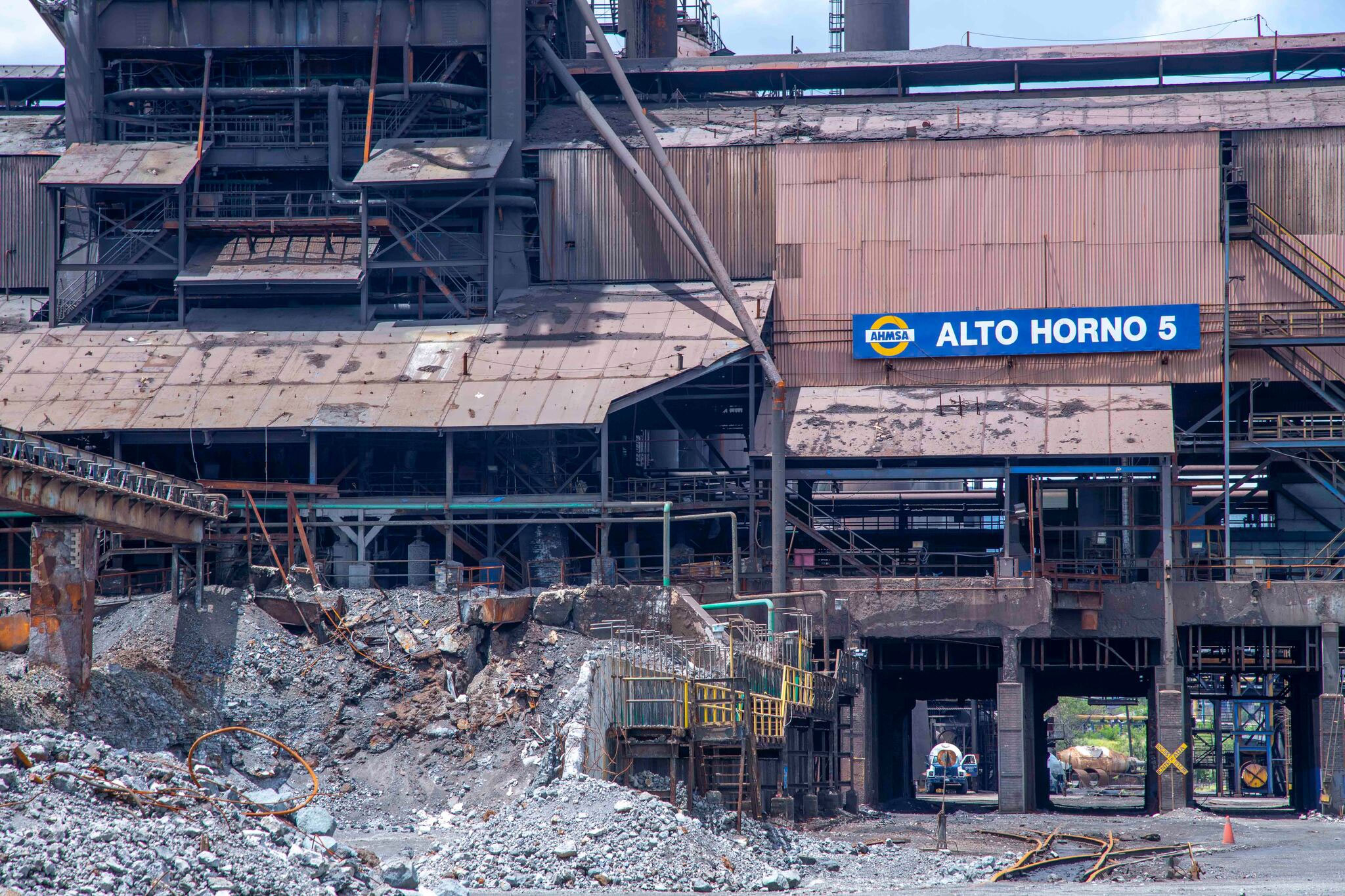

Saltillo. First the lights went out. Then departments began to close, one after another, as if the plant had begun to die from the inside. Workers walked among motionless machines, silent warehouses, and offices where not even a radio could be heard.

“The lights went out… and that was the end of everything,” says Alejandro Ortiz Valdés, 36 years of service.

Sometimes they were allowed in with guards, under portable lamps, to check that nothing was “invaded.” Then came the final order: never come back.

Since that blackout, they themselves say, more than 70 colleagues have died in the region. Not all of them died from illnesses; at least a dozen took their own lives. Others faded away from strokes, accumulated stress, and the anxiety of not having a salary, severance pay, or any answers.

Alejandro remembers precisely when the company stopped beating. The lines that once roared fell silent. The hallways began to smell of decay.

“We used to go in without doing anything, without light, just to look around. We were shadows in there. Then not even that anymore.”

Since then, he lives off whatever work comes his way: gardening, painting, “the odd repair here and there.” He doesn’t join any formal company “so as not to lose his rights ,” in case he ever gets laid off.

“They’re just giving us painkillers. Three years without a salary… and people are dying of despair,” he says.

Luis Alberto Martínez Vázquez worked for 42 years at AHMSA. He left in 2022, while the company was still operating, and has been waiting ever since for a severance payment that never arrived.

“Bankruptcy wasn’t what brought us down. It was mismanagement at the top,” he says.

He lives on a minimum pension, enough for him and his wife, but watches as the lives of his colleagues fall apart.

“Those are the ones who have fallen: the sick, strokes… and others who couldn’t take it anymore and took their own lives.”

“The union doesn’t exist”: Leonardo

Leonardo Rodríguez Sonora worked at the steel company for over four decades. In 2019, he left without receiving his severance pay.

“The company was alive. What came after was mismanagement and a union that never defended anyone. When you claimed your rights, they punished you,” he explains.

In his view, the death of so many workers is not a coincidence: “It’s neglect. Years of neglect.”

Adrián Carmona Ramos worked in the coal mines for 40 years. He thought that upon retiring he would close his chapter with dignity.

“I’ve been waiting four years for my graduation,” he says. “Many of my colleagues have already died. The more time passes, the fewer of us there are. We want something done before it’s our turn.”

“There are more than 70 dead… and several by suicide”: Benjamin

Benjamín Silva Pineda, secretary of the board of directors of the Exobreros de Coahuila Association, carries on his cell phone a mixture of grief and memory: photos sent by families, wake notices, messages that arrive at any time.

“Stress, despair, lack of support… all of that has killed many of our colleagues,” he says. “We have more than 70 deaths since this started. And of those, I estimate about ten took their own lives.”

Benjamin says that many families were left completely abandoned: without a pension, without severance pay, without recognized weeks of work.

“The widows are left with nothing. Many children dropped out of school. Many workers died waiting for someone to listen to them.”

For him, there is also a moral responsibility of the union that was created to protect the company and not the workers: “They repressed us, they marginalized us for not agreeing with that employers’ union. And today we are all paying the consequences.”

Walking as a Last Resort

The walk from Castaños and Monclova wasn’t just a protest: it was therapy, exhaustion, and a way to remember. Around 300 people set out; about 100 walked all the way to Saltillo. The rest accompanied them in pickup trucks and a trailer.

They slept in gas stations, in ranch yards, in borrowed houses. There were cold nights, donated food, makeshift stoves.

“People took care of us. They know that we were left with nothing,” said Adrián Carmona.

In front of Congress, they stood guard while awaiting federal intervention. And it arrived: the representative of the Interior Ministry in Coahuila, Juan Dávila, met with them.

According to Julián Torres Ávalos, leader of the movement, they were finally told what they had been asking for for a year: “They told us yes. That now there will be a meeting with President Claudia Sheinbaum . And that we won’t have to walk all the way to Mexico City,” he explained.

But he said it cautiously, without triumphalism: “We want a solution, not another promise. That’s all we’re asking for.”

A Debt of More Than 6 billion

While they were walking, in Mexico City, trustee Víctor Manuel Aguilera Gómez appeared before the Senate Special Commission in charge of monitoring the bankruptcy.

There he described a cold, technical landscape: “The company carries a debt of over 61 billion pesos . The appraisal of the Production Unit was set at 132.6 million dollars, and a minimum starting bid of 112.7 million was established for the auction.” He also stated that eight investment groups—both national and international—have expressed interest in acquiring the steel plant, along with the iron and coal mines.

He explained why they had sold “non-core” assets: mining concessions in Oaxaca, Colima, and Jalisco; various properties; and even their stake in the Coahuila-Durango railway line. He stated that these resources were used to prevent greater damage: floods, leaks, and failures caused by neglect.

Then he issued the toughest warning: “If the process does not move forward, the real risk is the definitive closure and with it the loss of more than ten thousand direct jobs.”

-

Not By Bread Alone…

Returning to the Mesoamerican milpa agricutlural system could revitalize agriculture, while defending Mexicans and Mexico from a tangled, global necro-politics.

-

Socialism & Anti-imperialism in Mexico During the 1970s & 1980s

Widespread anti-imperialist mobilizations served as a pressure mechanism against the subservient and collaborationist policies of regional governments.

-

Iranian Ambassador Asks Mexico to Condemn US & Israeli’s Illegal Attacks

The Ambassador confirmed 106 young children were confirmed murdered after the US & Israel regimes bombed a girl’s school.