A Strategic Cross-Border Labor Alliance

This interview was originally published by the UCLA Center for Mexican Studies (CMS) and the UCLA Institute for Research on Labor and Employment (IRLE) Institute for Mexican Studies at UCLA and appears here courtesy the author.

For over two decades, Benedicto Martinez was General Secretary of the Authentic Labor Front (FAT), one of the most important independent and progressive union federations in Mexico. During the same period, Robin Alexander was Director of International Relations for the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America, an industrial union originally founded for workers in the electrical industry, and a bastion of democratic, rank-and-file unionism in the U.S.

In the leadup to the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement, the two unions formed a strategic alliance to help organize factories in Mexico and the U.S., and to advocate for political change to meet the needs of the workers of both countries. The alliance has been a model for relations between U.S. and Mexican unions.

In this interview, the two explain how the alliance was formed, what its principles were and what it achieved. They reflect on the changes caused by Mexico’s new labor law reform and the new Mexico, U.S., Canada Agreement (called T-MEC in Mexico), which replaced the old NAFTA. The interview has been edited for clarity.

Alexander deals in more detail with this history in her new book, International Solidarity in Action, available from the UE here.

Robin Alexander: When we began the UE’s relationship with the FAT, neoliberal economic policies had caused the loss of thousands of jobs in our union. Companies moved them to other countries, mainly to Mexico. Our leaders thought it might be possible to find a union ally in Mexico, willing to try to reorganize these companies. In the United States, we could help, because we still had a presence in U.S. plants. At that time we had a relationship, more a paper one than a deep relationship, with the Mexican Union of Electrical Workers (SME). It is a very democratic union, but at that time it was in a more conservative period. The free trade agreement was on the horizon, and the SME’s leader, Jorge Sanchez, supported the policy of the Mexican government, which was negotiating it.

At a UE convention, the UE in Canada talked about the very negative impact of the U.S-Canada free trade agreement on Canadian workers. Then a representative from the SME spoke in favor of a trade agreement with Mexico. This clash was the point when UE leaders thought, we have to look for another relationship.

Benedicto Martinez: At that time the Authentic Labor Front (FAT) had a relationship going back many years with the National Union Confederation of Quebec, the CSN. We had both left the Latin American Confederation of Labor because we didn’t agree with the policy of Christian Democracy. When we began to hear about a free trade agreement between Mexico, the United States and Canada, the CSN came to Mexico to meet with us. They described their experience with the trade agreement between Canada and the United States. For them, it led to a loss of jobs and they wanted to organize a defense.

At the same time, the FAT began working with other organizations in Mexico to form the Mexican Action Network Against Free Trade (REMALC). The network gave us a way to look for allies in the United States, but our relationships had been with non-governmental organizations. The AFL CIO at that time had an open relationship with the CTM, which supported the policies of the government of President Carlos Salinas.

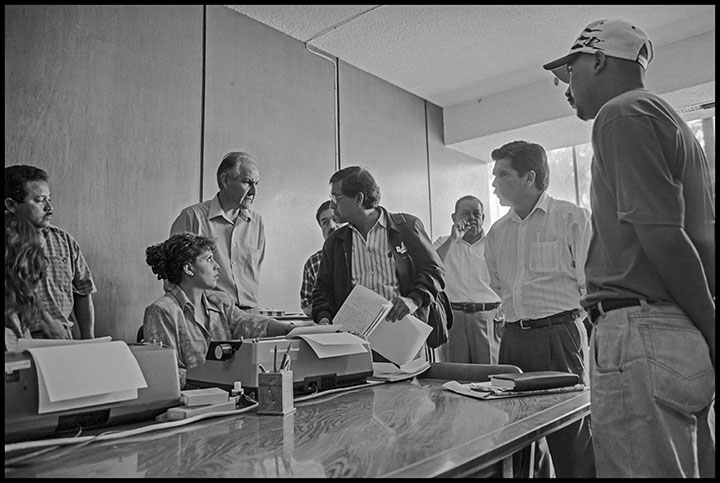

In 1992 a representative of the UE came to a REMALC meeting in Zacatecas. I was negotiating a contract in Aguascalientes, and on a day when we didn’t have talks, I went to the Zacatecas meeting too. One of the FAT comrades, Manuel García, told me there was another trade unionist there, the only other one at the event. That’s how we found Bob Kingsley (former political director of the UE), who was also searching for an alliance with a Mexican union. A month later we were invited to Pittsburgh to meet with the UE leaders, Amy Newell, John Hovis and Ed Bruno.

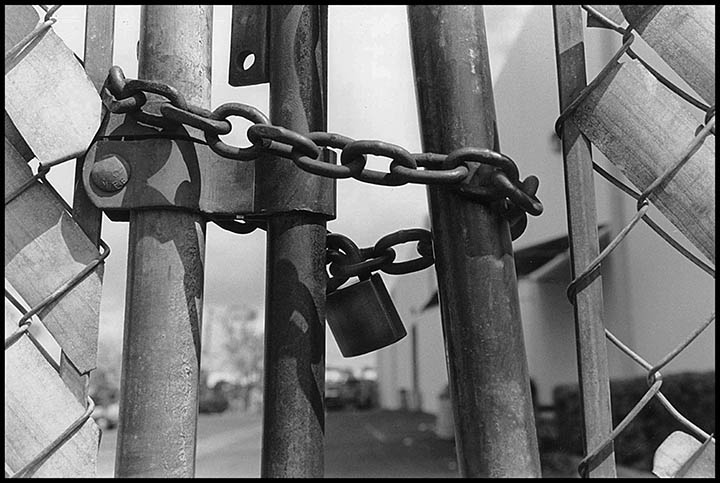

The UE felt the loss of jobs moving to Mexico, and wanted a relationship between workers in the United States and Mexico from the same company so that we could organize the runaway plants. We chose two plants that were among the largest — General Electric and Honeywell. We began a strategic alliance with an organizing approach. The speed surprised us — nothing was bureaucratic. We were soon working on putting together our contacts in Ciudad Juárez and Chihuahua.

We made the decision to start in Ciudad Juárez because there was already a study of the plants. There were possibilities in other states, but we did not have bases in some areas and in others, the FAT had been driven out. General Electric and Honeywell both had plants in Chihuahua, and although we did not really have a base of members in Ciudad Juárez, we did know people, so a small team went there.

I had been a member of the national FAT leadership since 1990, and had several organizing successes. So naturally the FAT said, we need a victim to coordinate this work in Ciudad Juárez and that victim was me. I was put in charge of the project and establishing the UE-FAT relationship.

I had not had the opportunity to go to the United States before. I was still very stuck in the factory. However, some things surprised us, like the way we were received at the meeting with the UE’s leaders, as if we had been old friends. We quickly established things that were important. Respect for autonomy was treated as a principle, and everyone took responsibility for making decisions in their own area. In Mexico, it was up to us how to do things.

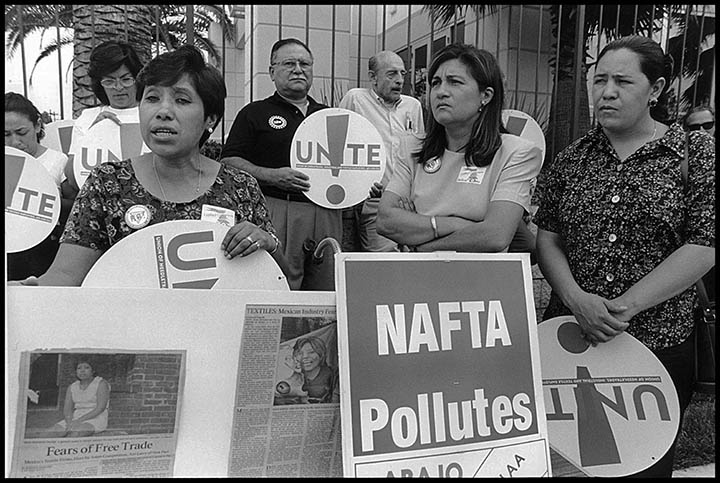

Alexander: There were two agreements between the UE and the FAT in ’92. One was to support the organizing in Mexico, involving plants belonging to companies where the UE had contracts in the U.S. We also agreed to organize a tour against the Free Trade Agreement in the United States, where representatives of the FAT would explain to workers why they thought it was a bad idea. The UE decided to establish a position of director of international relations.

It was a great challenge to develop international work in a way consistent with the UE’s principles, that we are a union led by the rank and file. That is a fundamental difference from the hierarchical way most unions operate. Many of our ideas then became key principles of the relationship between the UE and the FAT. We did things by consensus. The UE was responsible for what happened in the United States and the FAT for what happened in Mexico. There was permanent communication about what we were doing. In all the UE conventions from then on FAT representatives would speak with our members and we would develop the program for our work. We would exchange experiences about what we had done and plan for the future.

The first thing I did was accompany a delegation of grassroots UE representatives to Ciudad Juárez to support the organizing by the FAT against General Electric. This delegation was the first of many exchanges between the UE and the FAT. We didn’t just organize delegations from one country, but from both – by the UE to Mexico and by the FAT to the United States. We had cultural exchanges where murals were painted in both countries. There was a book project, in which a writer in the U.S. worked with a writer in Mexico to produce two books, one in English and the other in Spanish.

The relationship with the FAT was possible because we had a shared perspective about politics. We both had a commitment to organize democratic, independent unions.

The campaign at General Electric failed, and we realized that we had not really understood well the complexity of organizing in Mexico, and all the barriers to it. I give a lot of credit to the UE leaders of that time because the reaction of many unions would have been “we cannot do it,” or “it was a good try.” But the UE, recognizing all the difficulties, said, “this is an important relationship and we are going to continue supporting the FAT.”

The FAT at that time also made the decision to continue. To support them we made the first complaints under the NAFTA labor side agreement. We had no confidence that we were going to win by making them, but they provided a platform for the FAT and allies in Mexico to denounce the illegal actions of the companies.

Martinez: Sometimes it felt a little uncomfortable. Usually, when someone provides financial support they make the decisions, they command. In this case, it was different. We were fighting for the same cause in Mexico, and money meant more help organizing the workers. The situation in Ciudad Juárez was so difficult. We built a democratic movement based on the strength of the workers and were finally able to present the demand for a collective contract. But the state government flatly denied us. They openly said, “we are not going to process your claim.” It was a brutal blow, but they were the authority. They could do it.

The UE understood that under normal conditions, we would surely have won, but at GE and Honeywell we couldn’t, because the state forces were so strong. The principles we raised in those NAFTA complaints were finally written into the Federal Labor Law reform. That reform came out of those attacks against freedom of association and collective contracting, and the lack of justice at the federal and local conciliation boards. Today we have some protections in the law, but they came from the battles we fought 30 years ago.

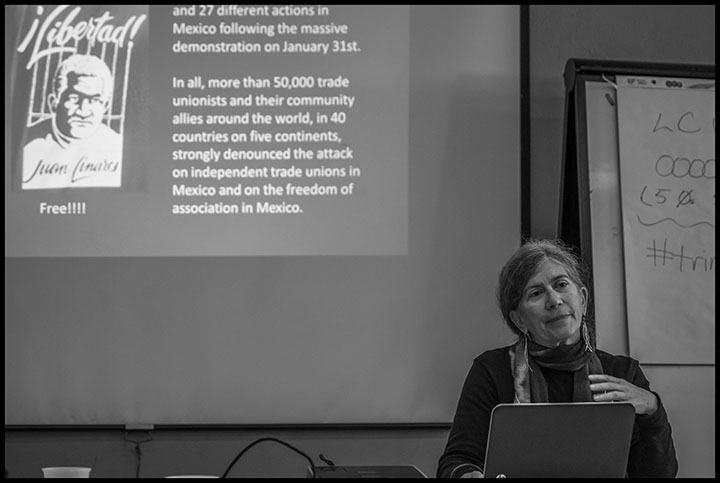

It was difficult because the resources the UE provided came from workers’ dues. If we didn’t win, how could they justify the expense? Asking that made us see ourselves differently – that we had to have a long-term perspective. If we had said 30 years ago that we would reform Mexico’s labor law in 2019, people would have said we were crazy. But we planted the seeds for it little by little. Our approach was to make visible the reality in Mexico – the lack of freedom, the lack of democracy, the lack of rights of Mexican workers – and to get other organizations and unions to take it on. Eventually, they did, even questioning these violations at the ILO. We also had allies, like the CGT in France and the CGIL in Italy, the Brazilians and the Chileans.

Because of the complaints under the NAFTA side agreement and another at the ILO, we began to have more influence on other unions in the U.S. At first it was just with locals of national unions like the autoworkers. But eventually, we were able to exert pressure in the AFL CIO itself. I participated in a tour of Teamster union locals in the U.S., at the time of their democratization when their president was Ron Carey. There was a march in San Francisco and another in Santa Ana.

We did grassroots work in local unions because the leadership of most U.S. unions maintained a relationship with the CTM and the Congreso de Trabajo (the government-controlled union federations). But it was hard. On the first tour, I was attacked by people who would call us “fucking Mexicans who come here to ask for help” or “they are the ones who are going to get the jobs.” They said Mexico was willing to accept low salaries to get those jobs. We knew people in those meetings were not going to receive us with applause because they did not know the conditions – that it was not a policy of the workers, but of companies in alliance with neoliberal governments. We’d explain that losing jobs was a product of the companies’ policy of transferring them.

Our relationship with the UE was very different. Although we worked mainly on organizing workers in Mexico, we needed to have allies from the same company in the United States, to be able to negotiate together. Our dream was to one day negotiate a contract with General Electric that would also cover Mexican workers. And little by little this relationship came to include a vision beyond that.

At the beginning of the UE-FAT relationship, we tried talking with workers at a plant belonging to DMI/Metaldyne, but it was difficult. Workers had relatively good salaries. Many worked on numerically controlled equipment and were specialists not interested in the union. But time passed and we kept at it because it had a sister plant in the United States where workers belonged to the UE. About 15 years after we started workers got interested because the salary conditions changed. It took two years before we could demand recognition, but it became our first success organizing a plant with a sister plant in the United States.

We had the first meeting with coworkers who came from the U.S. plant to Mexico and later a delegation from Mexico to the plant in the United States. It was a little like family. They could see their machines were the same, although they were working under different conditions, and obviously different salaries. But it was a big success for our alliance, after many years. In this long-term relationship, it’s not always the immediate gain that is the most important. We may want results tomorrow, but things are not like that in the union world.

Alexander: Another early campaign was a company called ISKO. One of the workers from the General Electric struggle in Ciudad Juárez became an organizer. He was sent by the FAT to work in Milwaukee in December. Because of the cold, it must have been the worst season of his life, but with his help, we won that campaign. It was very important because when he went home he could say the UE was not like other Mexican unions and this had an important resonance in his plant. Solidarity is not only about economic support, or just from north to south. Solidarity also meant supporting organizing in the United States.

One delegation we sent to Mexico asked to focus on the legal right to bargain. These were workers from North Carolina, a state where public sector workers do not have the right to collective bargaining. After this exchange, they returned to North Carolina saying they’d learned this was a violation of international law. They organized the North Carolina International Justice Campaign, which had a great impact. Then the FAT also filed a lawsuit under NAFTA’s labor side agreement. In other UE locals, workers began talking about it, that the FAT was fighting for the rights of UE members. It was very encouraging.

Martinez: Now things are changing because of the labor reform. Companies in Mexico that used to have a protection union (a company-controlled union) now think they’re better off without a union at all, in the style of the United States. So one lesson we have to learn is that solidarity and support doesn’t just flow from the north to the south, but in both directions.

The reform of the Federal Labor Law and the constitutional reform have led to the disappearance of the old labor boards and mandated free, direct and secret personal voting. Whatever comes next I think it will be difficult to reverse this, because another reform would require a 2/3 vote both in the chamber of deputies and senate. I’m not saying it’s not possible, but it would be complicated. So I think there is a certain security.

However, to date, the 12 complaints using the new T-MEC treaty only cover certain sectors of the industry. The treaty has not affected all unions or all national industries, but only those affected by the T-MEC mechanism. In terms of the country, that’s quite slow. Mexico has more than 50,000,000 workers, and these complaints cover at most 20,000 – small compared to our larger class.

We have won a mechanism, the voting, and a process for the recognition, but this process leads to rapid struggles and union formation. But building democratic unionism, with class-conscious workers, does not happen overnight. It requires education, which in the past came through conflicts. I don’t want to say that what happened in the past was good, but the more conflict and the longer the struggle, the more people learned. Their consciousness grew also because they had to prepare and read. When workers had to sustain a long-term struggle, they would gain more awareness of what is possible.

Today organizing is faster, but if we do not manage to create class consciousness, and commitment to democratic and militant unionism, I don’t know what the result will be. It could easily be a purely economic struggle. And that’s where I have my doubts and concerns.

Neither the CTM unions nor the established independent unions are organizing. It is not on their radar. The new actors are ones that have obtained resources through the Solidarity Center, like La Liga Obrera Mexicana, which are completely new, or like Julia Quiñones, who has spent her life working on the border, or Hector de la Cueva and CILAS (the Center for Labor Investigation and Union Counsel). But the campaign at General Motors came from a previous struggle among a group of workers who started the movement in the Silao plant. Resources came in and we know what happened. So those who are using the T-MEC process are the ones who are organizing.

Not all are successful and often present a new set of problems. VU Manufacturing in Piedras Negras, where they also used the T-MEC, is about to close the plant. In another plant with 1600 workers about 700 voted and 900 did not. SINTIA (the new union that won the election and contract at General Motors) won with 20 votes. It’s going to be very difficult to form a union if they win the support of 300 workers in a plant of 1600. It is really a minority union.

But the traditional unions, the old independent unions, don’t even appear in this. It’s as if they are not interested, and just administered what they have. It is not clear where our labor movement is going, or what it will really be after the reform process. The (old formerly government-controlled) unions of the Labor Congress – the CTM, the CROC, the CROM – are supposedly now in compliance, with legitimized contracts, and elections they say were free, with direct and secret voting. How can workers tell the new unionism apart from these unions that still operate as they did before?

Nevertheless, the economic situation for workers has improved with the considerable increase in the minimum wage. A larger budget for social expenditures has also made life better, especially for the most unprotected workers. It has not reached the level we would like, but it is on an upward path.

Alexander: Important things have happened, like this administration’s policy of putting the poor first. There are programs for older people, for students, and for young people. They’ve provided many more resources to the poorest people. For workers in particular the big increase in the minimum wage was a very big change.

During the years of our alliance, the Mexican government resolved labor issues directly or through the labor boards. That has also changed. Now the federal government says it is up to the parties to resolve labor issues, and they do not take sides. This is encouraging for the future. And, obviously, labor reform has created opportunities to organize without many of the obstacles that existed before.

However, there has been a lot of money, millions of dollars, coming from Canada and the United States to support this new unionism. We won’t know its impact for a while. Unionism in the United States is not a model workers should follow, and I don’t know the purpose of so much money. This is not a criticism of what has happened, but I am concerned about the unions that are being formed now. How democratic will they be? And if the money comes from the United States and Canada, what will happen when it’s taken away? The new unions are depending on T-MEC’s new rapid response mechanism. I hope that Trump does not win, but if he does, I cannot imagine that the rapid response mechanism will work as it has.

However, the organizing situation for workers now in the United States is very encouraging. There is movement, especially among young people, and we will also see where it goes. The UE has been very successful in organizing graduate students from universities, who are starting to win contracts. If this process continues, the UE will be in a much better position to focus again on international solidarity.

Martinez: I worry that the growth of new unions is based a lot on the present resources. But the status of the people who organize has changed, with high salaries for an organizer. In the past, you couldn’t even dream of this. If these resources stop, will the organizers continue?

In our old culture workers paid the costs, which kept expenses low. For a meeting today 40 or 50 people might attend, all paid, in good hotels. That wasn’t the case in the past. I don’t want to say that we should live in misery, but you get used to it and that’s the problem. For the worker, if a meeting means going to a good hotel with good meals, traveling by plane, what will happen when there are no resources for this?

I hope the union movement will re-emerge as all of us dream – strong, democratic organizations, with a relationship beyond our borders, as we managed to build with our alliance. The FAT’s dream for more than 40 years is organizing unions by industry branch and by company. With General Motors, a contract covering the whole company could be powerful, or a strong alliance able to negotiate collective contracts in different countries, respecting autonomy and cultures. The capital is the same, right?

Alexander: It’s a very important moment, and I feel a little bad about being retired. I would like to be 20 years younger and get back into it. But I believe that the experience we had with the FAT provides some lessons. I hope it’s something we can contribute to this new generation.