Big Trouble at the Camino Rojo Mine

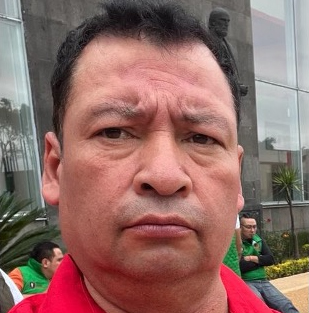

Jaime Pulido León was a mine worker and leader of the local chapter of the Los Mineros mineworkers’ union. Was. Death threats drove him and the union out of the mine and even out of the state of Zacatecas.

The conflict between the owning class and the working class is nowhere so up close and personal as in the workplace, and the owners hold all the cards. When the door to your workplace shuts behind you, you leave your rights outside.

The bosses can tell you whatever lies they want — like why unions are corrupt outsiders who just want your dues money. They can force you to sit through meetings to listen to anti-union propaganda. They can forbid you to talk about a union or to hold meetings in the lunchroom. Surveillance cameras are a usual business practice; Big Brother is watching. Worker leaders, “troublemakers,” are fired. The law upholds company rights — the law made by the owning class with their friends in government.

And in Mexico, companies don’t just use velvet gloves that leave no visible marks to suppress workers; they still use iron gloves as well. They have no moral qualms about hiring thugs to quash worker organizing. “Choose — vote for your independent union or stay alive!” Canadian mining companies are particularly brutal; their uncompromising determination to maintain total control is well known.

Today we hear from Jaime Pulido, a local leader of Los Mineros (National Union of Mine, Metal, Steel and Allied Workers), who was lucky enough to have survived the thugs’ attacks. Given the ruthlessness of the Canadian owners, it’s not surprising that they are winning at the Camino Rojo mine. The next question is, do workers have other methods to carry their rights into the workplace, past the figurative and literal guards at the company door? Can international workers walk with them? Can workers of the world unite?

Armed gunmen broke into your home because of your union activity. What happened?

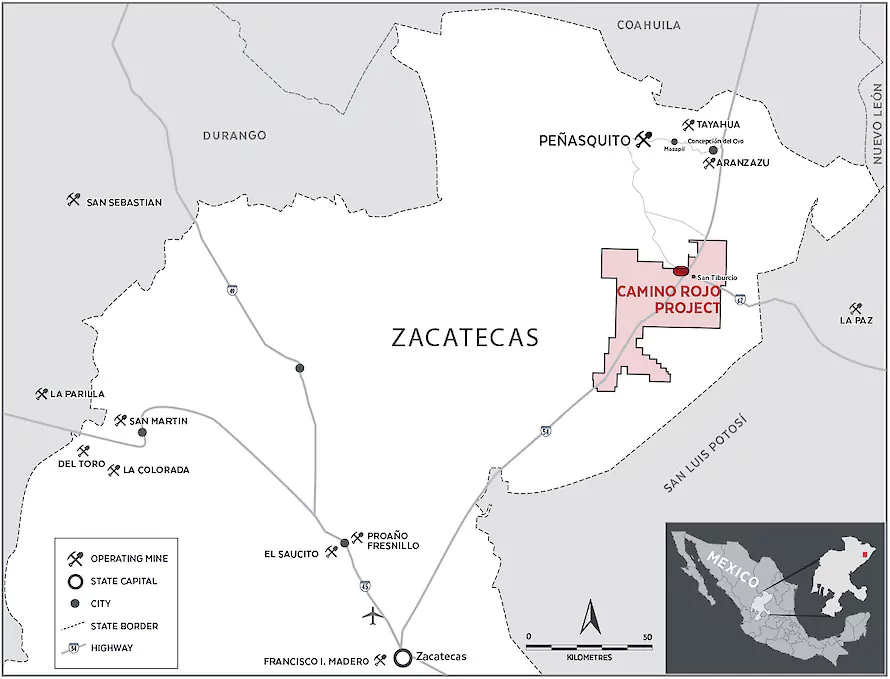

In April, gunmen threatened me. They told me to stop fighting for the rights of my fellow workers at the Camino Rojo mine, where we are all members of Los Mineros. I have two daughters in primary school. To keep them safe, my wife and I left the Mazapíl area of Zacatecas, where the mine is located, and moved from Zacatecas to Coahuila state.

On July 12, we went back to Mazapil to get my daughters’ papers to change schools. A truck with six armed men inside intercepted my car. They blocked the road. I got out of the car so that if they shot me, they wouldn’t shoot my family. They beat me. Then again, armed men entered my house on September 29. I was already in Coahuila.

These guys are part of an organized criminal group that does money laundering and other illegal activities. It’s local, but it’s part of the Sinaloa Cartel. Camino Rojo hired them to get rid of Los Mineros as the workers’ representative union. The police work with these criminals too. We have no protection.

Tell us about the Camino Rojo mining company.

The Canadian company, Orla, owns it. It’s an open-pit mine, and it has some of the richest ore deposits even for Zacatecas state, which produces more mineral resources than anywhere else in the country. Last year, 97% of what workers mined was gold, and 3% was silver. At first, they predicted that the ground had enough to keep the mine open for ten years, producing 94,000 oz of gold and 597,000 oz of silver annually.

But now, after finding new veins of lead, zinc and manganese, they say they can keep the mine operating for another 30 or 40 years. This past year was a lot more profitable than they expected.

The mine opened in 2021, and I started working there in May. Los Mineros was officially recognized by the state as the workers’ representative in September of that year. I was elected Secretary. There are 300 employees, 160 in the union, the others in management or working as administrative employees.

The company boasts that they are a “socially responsible” business that supports workers and the community. They have some programs for kids that are good publicity — they like to take a lot of photos! But the cost to them compared to what they make is like a few pesos in your pocket.

What was the issue between the union and the company?

In Mexico, we have a law that large companies must share their profits with their workers. The Employee Participation in Company Profits, or PTU, requires companies to distribute 10% of their profits to their workers. Camino Rojo made 10 billion dollars. They were supposed to pay us union workers 500,000 pesos each. They wouldn’t pay.

Mexican workers have the right to strike if they file a strike notice with the Department of Labor. We filed when the company refused to pay us what we were due. But instead, the company decided to replace our union with an outside charro union, one that would cooperate with the company against the workers. They wanted workers to sign cards for that other union and to ask for a new representation election, which requires 10% of the workers to sign. To make sure they got enough signatures, they hired criminals to drive to workers’ houses. Under threat, many signed.

In August, through the labor section of the USMCA, we filed a petition with the US Department of Labor to intervene since our rights were being violated. Our long-time president, Napoleón Gómez Urrutia — who once had his home invaded too and had to move to Canada — helped us with this. The US agreed that our complaint was valid. So then Camino Rojo offered us 70,000 pesos — far less than the 500,000 that we were entitled to.

A new representation election was scheduled for Friday, Nov. 22. Before that, the Canadian Steelworkers Union filed their own complaint under the USMCA, only the second time Canada has filed a complaint. As a result, the Mexican army was sent to protect the vote, and it went ahead as scheduled.

What was the result of the union representation election to replace Los Mineros with a charro union?

Before the election, once again, the criminals showed up at the homes of Los Mineros activists and told them to stay home; 90% of the workers live in three small villages near the mine. So the whole area was blanketed in fear.

At 6:00 AM, the sympathizers of the charro union showed up to push for a vote in their favor. I also went at 6:00 AM and stayed until noon. Six men inside a gray Silverado truck were watching me; they know my car. Three army trucks protected me when I went in to vote. They accompanied me on the 40-minute drive to the border of Zacatecas and Coahuila. At the border, a group of my friends was waiting for me.

Once I got to Coahuila, I was safe because the criminal gangs don’t go into Coahuila. They don’t work for the Coahuila government as they do in Zacatecas — and yet the governor of Zacatecas, David Monreal, is with Morena! It’s not surprising that Los Mineros lost the election, and probably the vote was corrupted.

Will you go back to work? What next?

Camino Rojo told me to come back, and they would “work things out,” but I know if I go back, I’ll be dead. I’m not going to file a complaint for myself; the judge is bought. Canada is looking the other way. We workers held a press conference in front of the Canadian embassy, but we didn’t get past the guard at the door. They wouldn’t let us in. They even called the police on us!

The Mexican, US and Canadian departments of labor — none of them has shown the willingness to pressure the company to fulfill their legal obligations to the workers, to guarantee our right to choose our own union representatives and to protect us from violence.

Breaking news: On December 12, the US Trade Representative asked for a new panel to discuss the denial of labor rights of Los Mineros activists; the US disagrees with the Mexican labor department that the issues have been resolved.