Campesinos Ride Again

This editorial by Victor M. Quintana S. originally appeared in the October 22, 2025 edition of La Jornada, Mexico’s premier left wing daily newspaper. The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Mexico Solidarity Media, or the Mexico Solidarity Project.

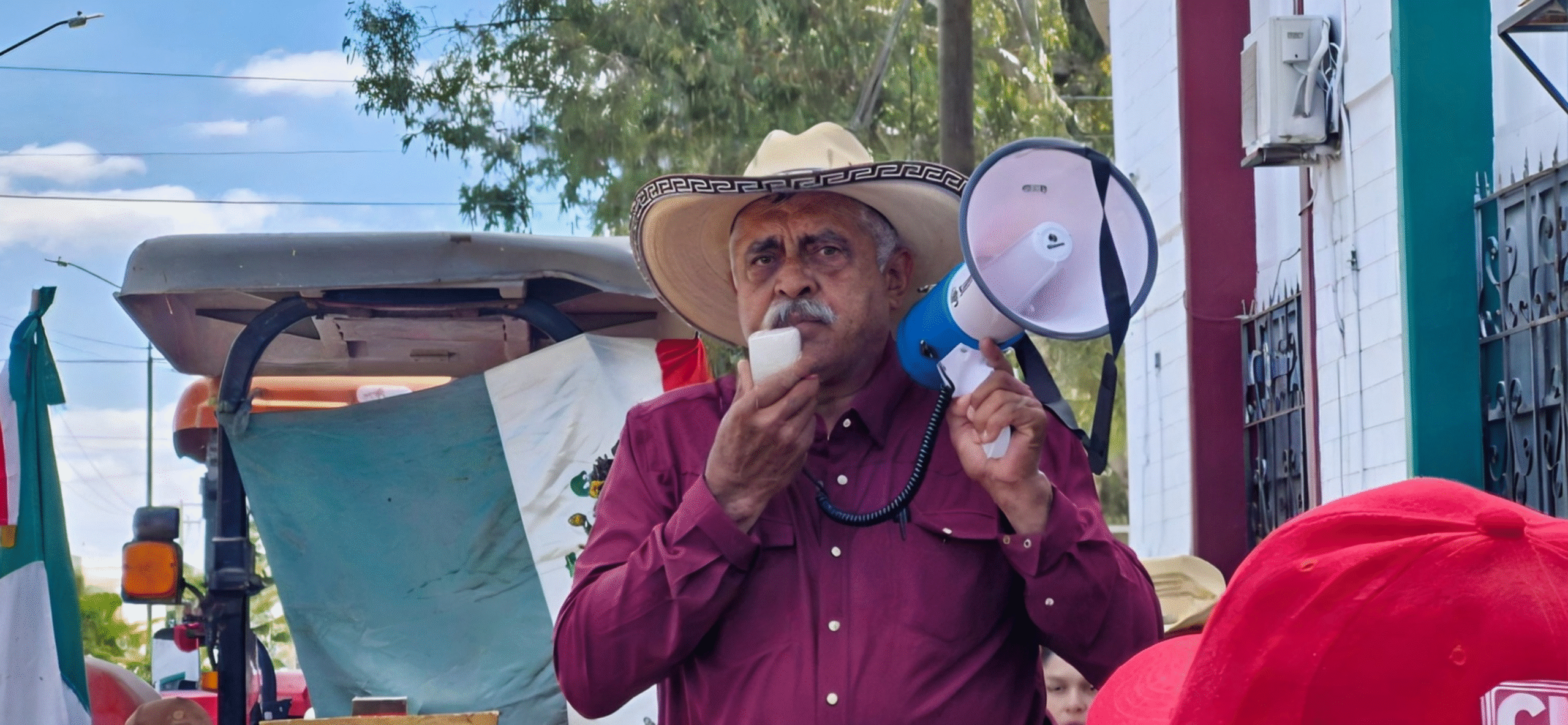

Medium-sized commercial agricultural producers are riding high again. Last Tuesday the 14th, they organized the National Agricultural Strike, which spread to at least 15 states in the country, especially in the north, center, and west, the main grain-producing regions.

They recall the great movement they led in the 1990s, against the first neoliberal onslaught that stripped them of a large portion of their productive assets and wealth in just a few months at the hands of banks under the pretext of overdue loans. Back then, they organized in El Barzón to defend their right to continue producing and living with dignity. Now, the National Front for the Rescue of the Mexican Countryside (FNRCM) is blocking roads, toll booths, and railroads with producers and machinery. Their main demands: the removal of basic grains from the USMCA and the Chicago Stock Exchange, guaranteed fair prices, and financing for their crops.

The current crisis differs from that of 30 years ago, although it is also a result of neoliberal agricultural policies. The governments of 1982-2018 and the entry into NAFTA in 1994 favored the growth of large agro-exporting companies, and Mexican state subsidies deepened rural inequality, concentrating it among large producers and marketers.

The first administration of the Fourth Transformation decided to redistribute support to those most neglected by neoliberal governments and implement programs such as Production for Well-being, Fertilizers for Well-being, Guaranteed Prices, and Sowing Life, which benefit more than 2 million producers living in poverty. However, medium-sized commercial producers have been left out, either completely or partially, although 90,000 of them are supported by the Special Electricity Program for Agricultural Irrigation (PEUA).

But this hasn’t been enough to raise basic grain production to the required levels, nor to keep this important segment of products and producers afloat. They themselves state this: they cannot compete with the uncontrolled entry of basic grains from the United States, heavily subsidized by that government, with prices set by the Chicago Stock Exchange. Furthermore, the costs of inputs, spare parts, machinery, and equipment consistently rise above the prices of grains. Rural financing is scarce and very expensive: they cite as an example the much higher interest rates charged for a tractor than for a luxury car.

Large monopolists, traders, and industrialists continue to obtain obscene profit margins to the detriment of producers and consumers.

The federal and state governments’ ability to acquire staple grain crops at guaranteed prices that are profitable for producers is very limited, and they alone cannot regulate the market. As a result, large monopolists, traders, and industrialists continue to obtain obscene profit margins to the detriment of producers and consumers. All of this could lead to the bankruptcy of thousands of medium-sized producers, the increase in rentism and the concentration of land among large producers and the monopolization of oligopolies and oligopsonies, the loss of the already deteriorating food sovereignty, and the invasion of genetically modified seeds, with the usual damage to biodiversity and national sovereignty.

The Secretariat of Agriculture and Rural Developmen (SADER) has acted responsibly and listened to the mobilized farmers on the ground. It has not dismissed the protests and has begun dialogue with some groups, such as corn farmers in the Bajío and western states.

Dialogue is always welcome, but it will soon dry up if it doesn’t translate into changes in policies and programs, which isn’t easy at this juncture: How can we exclude basic grains when there are fears that, in the renegotiation of the USMCA, Trump will seek to open markets for its grains when China and other countries have closed them off due to their aggressive tariffs? How can we maintain sufficient guaranteed prices with sufficient coverage of volumes and producers to reorganize the market when the federal government has such a tight budget? How, and above all, where, can we subsidize interest rates, equipment, machinery, agrochemicals, and energy so that commercial producers remain viable and domestic production of basic grains increases?

In dialogue, the government and producers must find solutions, even partial ones, and implement them. For example, one way to lower production costs is the one Colombia has used for the pharmaceutical sector and Mexico for textiles in the import market: a law establishing maximum reference prices for inputs and minimum purchase prices for producers. No one would be allowed to sell inputs or charge interest above X percentage of the reference price, nor would it be able to import grains below the reference production cost. This would not require a direct government outlay, but it would require significant capacity to coordinate the efforts of very diverse sectors.

You may or may not agree with some of the organizations or leaders of the domestic producers now protesting, but they deserve the full attention of the government and society.

It’s not just about their income; many public goods are at stake: food sovereignty, the country’s genetic heritage, and the strengthening and well-being of rural society.

-

People’s Mañanera February 9

President Sheinbaum’s daily press conference, with comments on scholarships, return of mining concessions, PRIAN exposed, Bad Bunny Super Bowl, and aid to Cuba.

-

8 Million App Users, TV Soap Opera Ad… & the PAN Still Can’t Find New Members

In Mexico, where political parties are currently publicly financed, the right wing PAN has spent a staggering amount during its lackluster recruitment drive.

-

Mexico’s National Film Archives Workers Demand Dignity

“Our struggle is legitimate; we are not asking for privileges or luxuries, only better working conditions and job security. We also seek dialogue. This situation has become unsustainable.”