Geopolitics & Mexico’s Power

This editorial by Fabrizio Lorusso appeared in the July 24, 2025 edition of Sin Embargo. The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Mexico Solidarity Project.

Who’s afraid of Mexico? How do people in Europe view the emergence of the Aztec nation? What does the country’s geopolitical power projection entail, seen from across the Atlantic?

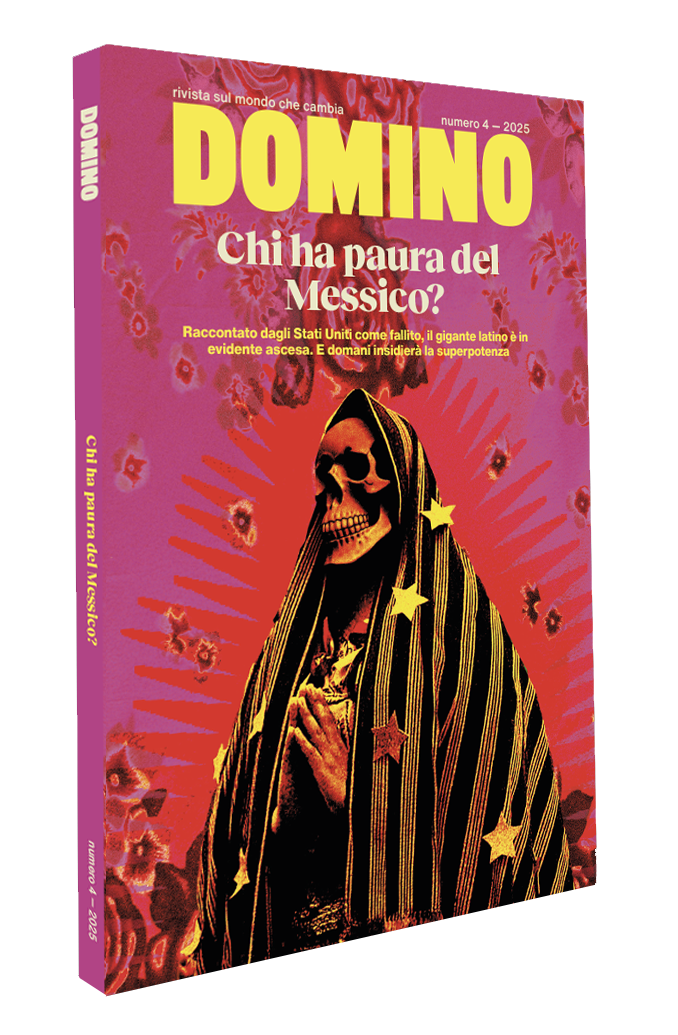

“The US narrative paints it as a failed state [or, in the sense of a “narco-state,” but the Latin giant is clearly on the rise. “And tomorrow it will threaten the superpower”: this was the subtitle of the April 2025 issue of Domino magazine, an Italian periodical of geopolitical analysis “on the changing world,” which proposes a vision, perhaps considered unorthodox in political and academic circles in the Global North, about the importance and destiny of Mexico.

With realism and without triumphalist tones, that is, recognizing the great challenges facing Mexico in the 21st century, its institutional failures, the gradual and physiological erosion of the demographic dividend, violence, inequalities, and the growth of economies and criminal groups, the volume emphasizes a series of interesting aspects, sometimes undervalued in these latitudes or out of focus in social and historical analyses, which are worth commenting on.

As a premise, I mention that back in 2017, the oldest Italian geopolitical magazine, Limes, had already dedicated a monographic dossier to the “power of Mexico,” highlighting how North America and the entire American continent have been dominated by a single, and in fact, almost unchallengeable, power. This status is a premise of US dominance over the planet, whether as a hegemon or as the predominant axis within a (today) relatively more multipolar world. The shielding of the northern continent, from Greenland to Panama, from Canada to the Caribbean, as a strategic objective of the Trump 2.0 administration, clashes with the possible emergence of rivals in this space.

First, and I’m removing the “s” from the plural of the word “rivals,” it’s clear that Mexico would be the only real antagonist or rival, in historical, cultural, even ideological, and perhaps economic terms, of the giant of the Stars & Stripes, and that it could compete, perhaps without displacing it, but certainly putting it into discussion, with part of the global power of the United States.

The US paints it as a failed state, but the Latin giant is clearly on the rise.

Not now, but tomorrow, or perhaps the day after. “The US elite and apparatus have firmly imprinted in their geopolitical memory the main thrust of the threats to US hegemony over North America: the southern flank, between Cuba and Mexico. And if the Caribbean archipelago appears strategically sterile after the end of the Cold War, the Mexican question is alive and well,” explained the back cover of Limes, using phrases that are still valid today.

But returning to Domino magazine and 2025, what scholars of Mexican-American relations highlight most are various factors that I will list, expand on, and comment on.

- The strong Mexican identity and “defensive nationalism,” as historian Lorenzo Meyer once conceptualized it, to survive American influence, undermining it from within;

- An active population boom with a median age still under 30 years old, which, while slowing its growth trajectory in Mexico, could also potentially be due to the huge Chicano and intergenerational demographic presence north of the Rio Grande.

- With the exception of the South and Southeast of Mexico, the spread of Protestant, Evangelical and Neo-Pentecostal religious denominations, vehicles of US influence and neoliberalism in the Latin American subcontinent, is still very limited in relation to the majority Catholic core which, despite fluctuations and criticism, maintains identity-based, historical, unifying and syncretic functions, even of assimilation and hybridization between Indigenous populations (which represents, of course, a process of origin, also violent, like all assimilation, and a legacy of colonial policies).

- The emergence of MAGA (the Make America Great Again movement), recharged by the second term of Trump and his company of radical supremacists, has had the effect of reinforcing certain forms of Latin and, above all, Chicano and Mexican nationalism and vindication in the United States, between protests against deportations and opposition to xenophobia, which can be exploited by the Sheinbaum Government: although, especially in the past, a part of the population in Mexico has considered expatriates as “traitors” or “outsiders”, before the United States finishes assimilating them, their reluctance to total fusion in the American melting pot and their roots in hybrid cultures “neither from here nor from there”, or based south of the Rio Grande, can constitute an important piece of the geopolitical chessboard in the future and a nightmare, which already exists in part, for gringos of Anglo-Saxon or Germanic stock.

- No other country has nearly 40 million fellow citizens or descendants in the heart of the United States, 12 percent of the US population and 60 percent of those considered “Latinos” (more than 65 million in total), among whom there are even, as minorities and latent, irredentist currents or, at least, distinctly identitarian and ideologically “mixed” movements.

- While Washington remains the main commercial and economic partner in the broadest sense, and Mexico continues to belong to the Western sphere under its threatening-protective “mantle”, the alternate geometries of rapprochement between Mexico City and Beijing, Moscow, the BRICS or Brazil itself and progressive Latin American governments represent a recurring headache among the apparatuses, agencies and executives north of the border: both Russia and China are respected powers in Mexico and, above all, are located far from its borders, and a basic geopolitical rule is that in times of difficulty or conflict, friction or excessive interference, the weaker “partner” or “client”, in this case Mexico vis-à-vis the United States, flirts and seeks diversification with more distant allied powers;

- The medium-term challenges identified are, on the one hand, the reconstruction of relations and partnership with Argentina, a key country, but one that has evidently succumbed in this phase to the IMF, Washington and israel since Macri and Milei took power, and on the other hand, the strengthening of the subcontinental link with Mesoamerica-Central America, beyond the South-South rhetoric, temporary projects or even security plans to control migratory flows and drug trafficking: Mexico City, typically in this 21st century, has looked less to the sister republics of the isthmus to configure zones of strategic cooperation or even influence, than to the nearby North.

In summary, the key factors for Mexico’s geopolitical rise, as seen from Europe, would be: its vibrant demographics; a certain homogeneity, not exempt from conflict and violence, of an identity-cultural nature; the idea-ideology of having moral, values, and spiritual superiority as a unifying narrative; the limited penetration of evangelical and “external” sects and denominations; moderate economic expansion, but with the recovery of strategic projects in energy, technology, resources, and commercial diversification, if achieved; the potential use of cross-border value chains, established after NAFTA-USMCA, and of nearshoring and access to the US market; the possibility, remote but noted by geopolitical analysts, of transforming or channeling internal violence and conflict into “other arenas,” such as the legal economy, defensive, or offensive potential; becoming a bridge or reference point for Latin America; and emphasizing the Mexican population at the heart of the superpower.

Beyond President Sheinbaum’s effective, thoughtful, and even sarcastic responses to Trump’s verbal attacks and bullying, and in the face of the “Gulf of America” versus “Mexican America” dialectic, current Mexican sovereignty, which receives internal criticism for its megaprojects or the “executive” concentration of powers, has, from an external perspective, seen from Italy, for example, managed to differentiate itself from that of Europe and the United States.

Here, it’s about reclaiming autonomy and resources, mutual respect, and the recovery of levers for the State and the national economy, not chauvinism, xenophobia, and the rejection of the “foreign other” and international rules. A text by Domino even comments that the reform of the judiciary can be read as a recovery of margins of autonomy and strategy based on this project, whose developments, however, we in Mexico must weigh, monitor, and criticize socially and politically, also in terms of expanding rights and deepening democracy.

Ultimately, Mexico could emerge as a regional and global benchmark for its balance, pragmatism, and results, in the face of the vast power asymmetries that will continue to prevail in the unstable environment of North America and the world for some time to come.

Fabrizio Lorusso is Professor and researcher at the Universidad Iberoamericana León on topics of violence, disappearances, and memory in the context of globalization and neoliberalism. He holds a Master’s and PhD in Latin American Studies (UNAM) and is a member of the Platform for Peace and Justice in Guanajuato, a project for the collective empowerment of victims.

-

Culture | Labor | News Briefs

Workers Occupy Culture Secretariat, Demand 13% Wage Increase

2,000 workers have been receiving incomes below Mexico’s minimum wage for over two years.

-

People’s Mañanera March 2

President Sheinbaum’s daily press conference, with comments on electoral reform, the gradual move to a 40 hour workweek, employment, national security strategy, and once again, the call for peace.

-

Mexican Delegation To Participate in April Global SUMUD Flotilla to Gaza

The aim is to work towards ending the genocide that the Israeli government—with the support of the governments of the EU & the fascist US government—is carrying out against the Palestinian people.