Health Care Where There Is No Doctor

Over Christmas vacation in 1965, my friend David Werner hitchhiked 1500 miles from California to Western Mexico. North of Mazatlán, he asked a truck driver, What’s in those mountains up there? Traveling up a dirt road for hours, he arrived at San Ignacio, a town above the Río Piaxtla. Hours beyond, the road ended at Ajoya, a stunning 400-year-old village at the base of the Sierra Madre. Ajoya had no electricity, the villagers drew water from a river below and, except for traditional healers, the village had no doctor.

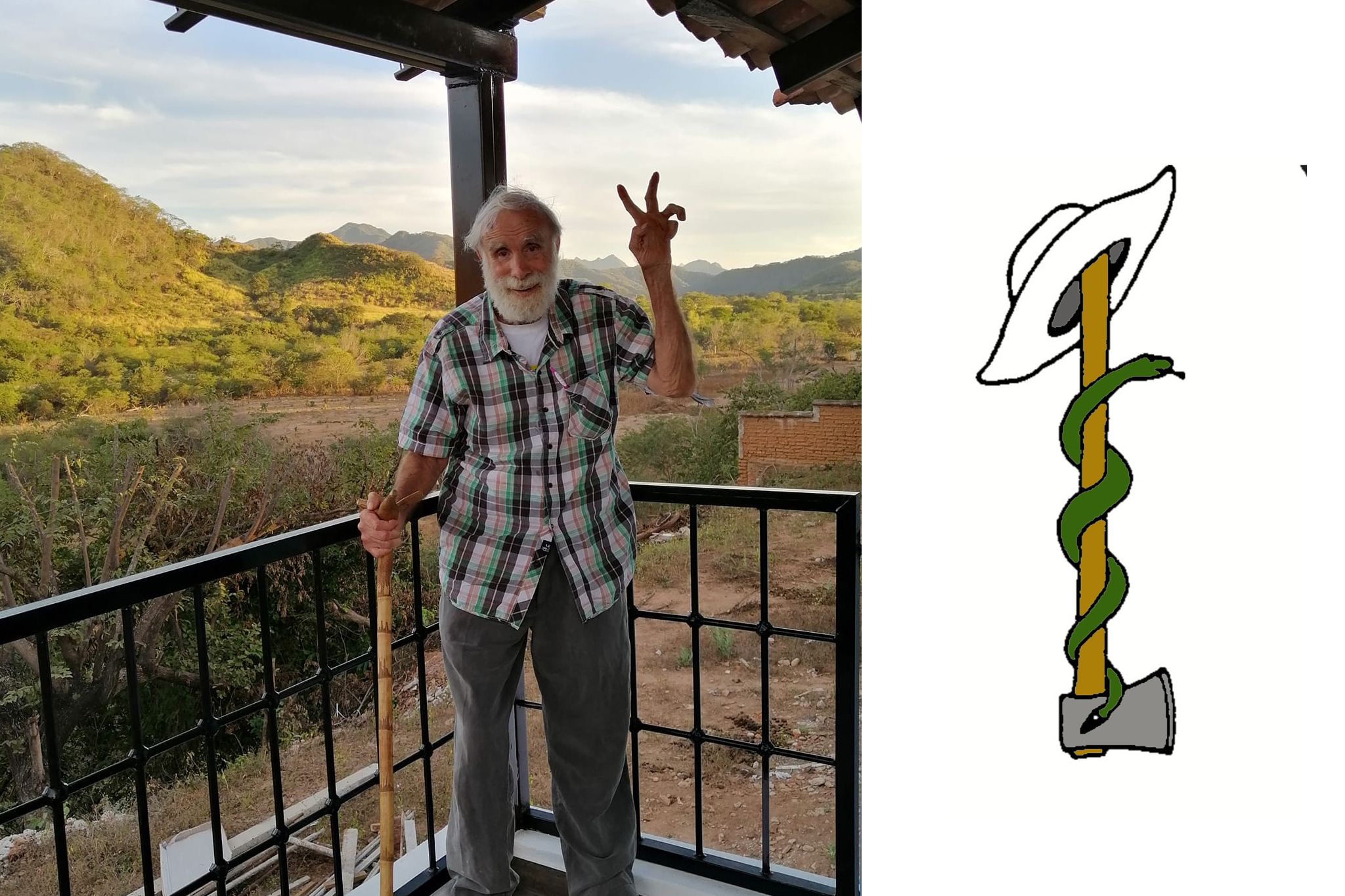

The following year, David quit teaching and returned to Ajoya. He intended to stay a year — he stayed over fifty. In the village, he and a team of promotores de salud (health promoters) organized Proyecto Piaxtla, the clinic and training program that created a network of health outposts throughout the mountain region.

In our interview with David, he told stories of his years in the Sierra Madre. Who would know that the collection of notes and illustrations he’d penciled as basic guides for the village health team was the genesis for the book Donde No Hay Doctor (Where There Is No Doctor)? Since 1973, David’s book has been translated into over 100 languages and is used by community-based health programs in poor communities throughout the world.

I met David in the early sixties, when he taught biology at an alternative high school in northern California. It offered college-level courses, promoted learning from direct experience in the natural world, and supported activism in the civil rights and anti-war movements.

Each year David took groups of students, including myself, to Mexico on ecological field studies. Our classroom was the Pacific Ocean, the Great Sonoran Desert, the Nayarit jungle, the mountains of the Sierra Madre. Based on intensive studies of a desert oasis in Sonora, three of us kids co-authored a cover story for Natural History magazine!

David Werner — who turned 90 in August — continues to write and comment on the struggles of the poor in rural Mexico, where he has lived since 1966.

David Werner, author and health and social justice activist, is co-founder and director of HealthWrights and was a visiting professor at Boston University’s International School of Public Health. A biologist and educator by training, he has worked for over 50 years in village health care, community-based rehabilitation, and Child-to-Child health initiatives in the global south, primarily in Mexico. From 1965 to the 1990s, he was an organizer and advisor to Project Piaxtla, a pioneering health program run by campesinos. This program contributed to the conceptualization and evolution of primary health care (PHC) globally.

You weren’t a doctor! What led you to work on health problems in rural Mexico?

No, I don’t have a medical background. I taught ecology in an alternative high school in California. Instead of starting with books, my classes started with field trips where students could observe for themselves and draw their own conclusions.

Looking for an ecologically diverse area to explore, I hitchhiked down to Mexico during Christmas vacation and hiked up into the mountains of the Sierra Madre toward villages reachable only on foot or horseback. With another school teacher, I hiked up into the high mountain area.

I returned down the mountain alone. The sun was setting, and I was still a long way from the next village. As I hurried by a simple stick-wall hut, a man came out and asked where I was going. I said “Bordontita.”

“Bordontita is too far to walk in the dark, and there are snakes and scorpions on the trail! Why don’t you stay with us!” For someone from the United States, such an offer was very unexpected, and I gladly accepted. He spoke to his young son, who limped out and came back with two eggs, which they cooked for me, while the family ate just boiled beans.

After eating, everyone bedded down for the night on the dirt floor. That night, even in my sleeping bag, I was cold. But the family slept on a deer skin with only three blankets for all seven of them. That night it was so cold that by 3 a.m., the family started a fire in the middle of the floor and sat around it with the young ones in their arms until dawn.

By the light of day, I noticed the limping boy had pus coming out the side of his foot. I asked him what happened. He said he’d stepped on a thorn — three months before!

I also noticed that two smaller children had large swellings on their throats, presumably goiters due to iodine deficiency, which can also cause deafness and mental slowness.

Back in California, I told my students about my experiences, and they were eager to learn more about the lives of the people I’d visited. The following spring, I took my first student group to the region.

We put together basic medical kits, and because most of the people couldn’t read, we made drawings about how to use the contents. We hiked for two weeks into the mountains, visiting many small villages.

On our hike, the villagers helped us as much or more than we helped them. In one remote village, we helped save the life of a little girl who had fallen into a fire pit. A few days later, high in the mountains, one of my students became ill with pleurisy and was almost unable to breathe. A local curandera (indigenous healer) taught us how to clear the phlegm from her lungs by having her breathe hot water vapors and likely saved her life. It was the villagers’ warmth and generosity that moved me to live with them — and perhaps contribute in some way.

I took a year off from teaching to go back to Mexico. My idea wasn’t to play doctor but to provide health information in the language of the local people. I got some basic training from a doctor in California and moved to the Sierra Madre.

What were the main causes for poor health? What treatments did they have?

The people had little or no money and almost no formal education. They had no access to antibiotics and other modern services, and although the government theoretically provided free TB treatment, it was unavailable in these villages. But the villagers did have a wealth of traditional healing skills and community spirit from which we could all learn.

A fundamental cause of poor health was the inequitable distribution of arable land. While a few wealthy families owned all the most fertile farmland, most of the poor used slash-and-burn farming to grow their corn and beans on the steep mountain sides. The poor and uncertain yield of their crops led to high levels of hunger and malnutrition, particularly of children.

What did the health program look like?

The village-run health program — Proyecto Piaxtla — developed in three basic stages. The first was the focus on curative treatment of poor health. The second was on preventative care. The third was on collective political action that focused on the root causes of poor health. We began with what the people wanted most, curative care. I didn’t treat many patients, but trained health workers, promotores de salud. The villagers themselves chose them and often selected local curanderas. The promotores charged little or nothing for the services, but the villagers often gave them food or helped with farming.

I began to write notes and make pencil drawings to help families in these remote areas diagnose and treat illness and injury. Those notes ultimately became the beginning of the handbook Where There Is No Doctor.

After about the first three years, we shifted our main focus to prevention. The government was supposed to provide vaccines against common diseases: polio, diphtheria, tetanus (the biggest killer of newborns), whooping cough and TB. But because vaccinations sometimes caused side effects, the villagers often rejected them.

So, we took action to inform the villagers about the importance of vaccinations. In one largely indigenous village, three sisters had had their ears pierced with the same thorn. Two had been vaccinated. The one who wasn’t died of tetanus a few weeks later. From this unfortunate incident, we developed a traveling theater skit to help the villagers understand the importance of vaccination. After that, people clamored for vaccinations.

The third stage was organizing political action to tackle the root causes of poor health. Through lively workshops, villagers analyzed that one of the biggest causes was inequitable land tenure.

A major issue — the rich people’s cattle were freed to eat the poor people’s crops planted on the steep hillsides. So the villagers began fencing their small farms. Then they banded together and built one fence around many plots.

As a result, Victor, one of the wealthy ranchers, went to a distant village and offered to pay someone to assassinate the organizers of the group protecting the crops. But those farmers not only refused, they told their neighbors about the plot. In response, a group ambushed Victor when he rode by on his horse and told him, “If any of us is killed, not even your dogs will survive!”

In the West, medical experts provide expensive services from the top down, which doesn’t work in rural Mexico. However, when the Sierra Madre villagers analyzed their needs and worked together, they greatly improved the health of their communities.

Within ten years after beginning the village health program, Proyecto Piaxtla, infant and maternal mortality dropped more than half.

The 2nd part of David Werner’s interview will focus on his work with the rehabilitation program in the Sierra Madre, Proyecto Projimo, organized by young disabled people.