Leftist Claudia Sheinbaum Wins Landslide Victory in Mexico Presidential Election

A nervous but hopeful energy filled the air on Sunday night at the Morena party’s election headquarters in downtown Mexico City. After a long and dirty campaign filled with sexist smears and antisemitic dog whistles aimed at the left-wing party’s presidential candidate Claudia Sheinbaum, supporters of the party, founded by outgoing Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, knew they had won — but given the risk of electoral subterfuge by the political opposition, they were not ready to celebrate yet.

Exit polls and the party’s own internal numbers indicated that Sheinbaum had not only beaten her opponent Xóchitl Gálvez, who ran on behalf of a hodgepodge opposition coalition that brought together historical rivals the National Action Party (PAN) and the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), but had won by an overwhelming 2:1 margin. However, in the weeks leading up to the June 2 vote, voices sympathetic to the opposition had suggested that in the event of a Gálvez defeat, she should challenge the results or even push to have courts annul them.

These political pundits have claimed — without evidence — that the government was running what in Mexico is known as a state election, rigging the process in favor of Sheinbaum. President López Obrador did attempt to reform the country’s electoral authority but his efforts were stymied by the opposition and the Supreme Court, meaning that the election was run under the same rules as 2018. Some critics also alleged that Morena was benefiting from support from recipients of social programs, claiming that voters were being coerced to vote for the ruling party under threat of losing access to social programs. However, the most popular of the social programs, the universal pension for seniors, was elevated to a constitutional right, meaning any effort to use them for a competitive edge had no basis in reality.

In May, commentator Denise Dresser alleged in Foreign Affairs that López Obrador and his Morena party, also known as the National Regeneration Movement, have presided over a democratic regression in the country. Ever since the 2018 election of López Obrador, members of Mexico’s liberal intelligentsia had been predicting that the president and Morena were seeking to return the country to the type of one-party authoritarian pseudo-democracy that dominated Mexico during the PRI’s 71-year rule.

Rafael Barajas Durán, one of Mexico’s most famous political cartoonists and the head of Morena’s political training institute, bristled at the notion that the movement was anything but democratic.

“The National Regeneration Movement was born fighting against state elections. It is a deeply democratic movement,” Barajas, also known as El Fisgón, told Truthout. “To accuse us of running a state election borders on the offensive.”

Indeed, the voices charging López Obrador with electoral misconduct, such as writer Héctor Aguilar Camín, were the same people calling on the population to vote for the PRI candidate in this election, Xóchitl Gálvez.

Barajas said their allegations do not hold up even to the slightest bit of scrutiny.

“In these last six years we have had several electoral processes, and the opposition has never been able to say that the government has perpetrated a fraud or that it has meddled in favor of a candidate,” he said.

While the electoral season was marred by political violence, it was mostly targeted at local candidates, with candidates from both the pro-government bloc and opposition coalition impacted by the violence.

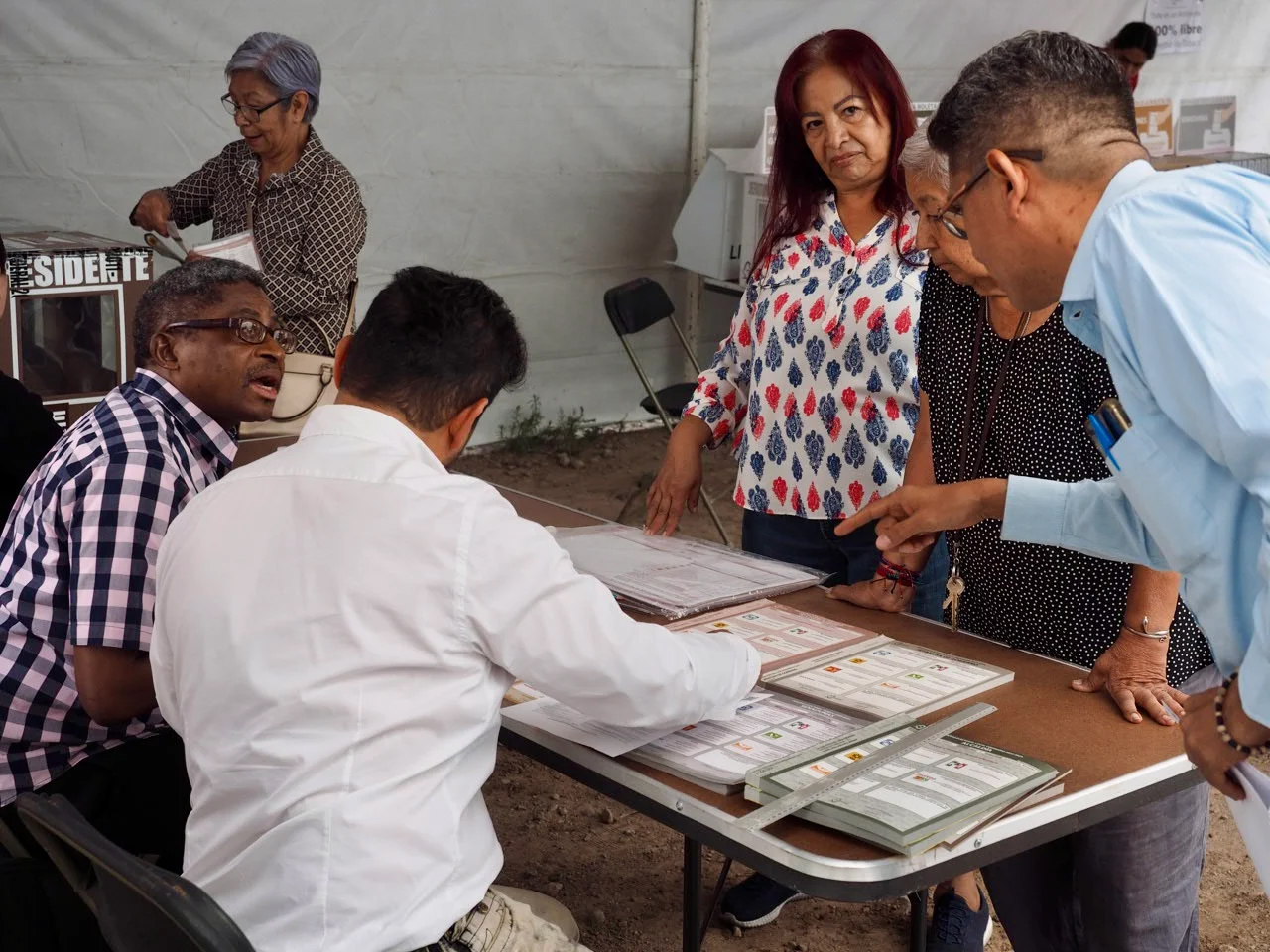

Nonetheless, in anticipation of the opposition’s expected fraud allegations, Morena invited a group of international election observers to monitor the electoral process, in addition to other observation delegations. Political leaders and organizers from throughout Latin America and beyond descended on Mexico City to supervise the vote, with permission from the country’s electoral authority.

Clara López Obregón, a Colombian senator representing the Historic Pact coalition that backs President Gustavo Petro and a member of the observation delegation, told Truthout that, based on what she saw, the vote was free and fair.

López Obregón, who has observed various other elections throughout the region, praised the democratic commitment of the Mexican population, who turned out early to vote in Sunday’s election.

“Many of the voters I spoke to at the voting centers and in the queues said that what was needed was a strong turnout so that there would be zero doubt of the electoral triumph because of a potentially close result,” said López.

Official figures from Mexico’s electoral authority put voter turnout at over 60 percent, in line with participation rates from previous presidential elections. López Obregón did observe some irregularities. Some polling locations opened late, and she suggested that the poll workers should receive better training to ensure a smoother process. However, none of the irregularities López witnessed would suggest that the end result was not an accurate reflection of the electorate’s wishes.

“Here they are respecting the [constitutional] guarantees of each and every one, and I would seriously object as an international observer if a fraud allegation was made,” López told Truthout.

Despite the overwhelming evidence that the election was free and fair, at one point early on in the night, before official results were released, Gálvez and her team appeared to seriously entertain the possibility that they would not recognize Sheinbaum’s victory.

In a press conference after polls had closed, Gálvez claimed she had won the election. The social media account of the parties backing her bid similarly shared since-deleted images claiming they had triumphed.

The uncertainty was not helped by the fact that the National Electoral Institute (INE) inexplicably delayed the publication of the so-called quick count. Mexico still largely relies on paper voting. While the official tally takes several days to be published, the quick count offers a projection of the likely results.

The quick count was expected at approximately 10 pm but ultimately was not shared by the head of the INE until shortly before midnight. The delay allowed Gálvez to feed speculation that something was amiss. In a series of posts to social media, she called on supporters to stay awake and vigilant. Her coalition’s candidate for head of government, Santiago Taboada, similarly refused to concede before the publication of the quick count, even dispatching workers to set up a stage at Mexico City’s Angel of Independence for his victory rally.

In the end, when the quick count was published, the narrative that the election was “stolen” was unsustainable. Both Gálvez and Taboada reluctantly conceded defeat, despite cries of fraud from supporters.

The quick count, which provides a small range of the expected result, showed that Sheinbaum had received between 58.3 and 60.7 percent of the vote, outperforming most polls, which had her around 55 percent. Gálvez received between 26 and 28.6 percent of the vote. A third candidate, Jorge Alvarez Máynez, came in a distant third with 9.9 to 10.8 percent of the vote.

With the release of the data, the tension that hung over supporters inside the Morena headquarters broke and those in attendance erupted into cheers. Sheinbaum addressed supporters well past midnight. At the start of her speech, she recognized the historical significance of her victory.

“For the first time in 200 years of the Republic, I will become the first woman president of Mexico,” declared Sheinbaum.

The landslide victory actually means Sheinbaum has received the highest vote percentage in Mexico’s democratic history, outpacing even her predecessor and mentor, López Obrador, who similarly won by a large margin in 2018.

“We are honoring the conscience of our great-grandmothers, of our grandmothers, today we can say that not only can women vote, but we are also being voted into office, and not only in the legislature, but to the highest office, the presidency of the republic,” National Coordinator of Young Women for Sheinbaum’s campaign Gracia Alzaga told Truthout.

Alzaga also pointed out that Sheinbaum’s dramatic victory also gives Morena and its allies much more room to operate in the national Congress. Morena had set out the lofty goal of not only winning a majority in the Congress but a supermajority that would allow them to carry out constitutional reforms without the need to negotiate with opposition parties. Results indicate that Morena and its allies have met that threshold in the lower house and are very close to a two-thirds majority in the Senate as well. In February, López Obrador proposed 20 wide-ranging reforms that the president says are aimed at restoring the “public, social and humanistic character” of the 1917 Constitution and will likely be considered by the new Congress before his term finishes at the end of September.

In her victory speech, Sheinbaum promised to carry out the legacy of López Obrador. On the campaign trail, she talked often about building the “second floor” of the political transformation started by her predecessor. Sheinbaum has committed to maintaining the fiscal discipline that characterized López Obrador’s government but also said she would expand the widely popular social programs and follow through on the major infrastructure projects already underway.

One area where Sheinbaum might differ from López Obrador is on climate change. She was a member of the United Nations panel of climate scientists that was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize and is expected to promote more green energy initiatives.

Sheinbaum nonetheless faces a tall order — her political adversaries will seek to exert their influence despite their reduced power in elected offices.

“What we are facing, what all the governments of Latin America are facing, are the de facto powers. What we are facing is the fact that winning the presidency, controlling congress, winning the governorships does not mean having power, power is a complex framework, so obviously there are things that we do not have control over,” Barajas told Truthout.

He warned that conservative forces have found refuge in the country’s private media outlets and count on allies in the judicial branch of government, and he predicts they will use these spaces to attack Sheinbaum’s government once in office. Barajas called on the U.S. public to “break the media blockade” and learn about the political transformation happening in Mexico.

“Processes of transformation have a peculiarity; in that they are very contagious. So, of course, what they are looking for is to isolate the information available and say that nothing happened here, to pretend that this did not happen,” said Barajas.

But something did happen in Mexico on June 2: true to Sheinbaum’s campaign slogan, history was made.

Copyright, Truthout.org. Reprinted with permission.

Source: Truthout.