Let’s Talk About Migration

This editorial by Diego Torres appears as the introduction to the September 2025 issue of Hablemos de Migración, a newsletter on migration issues published by the Frente Amplio de Mexicanos y Migrantes. We encourage you to subscribe. The English version of the September 2025 issue is available for download.

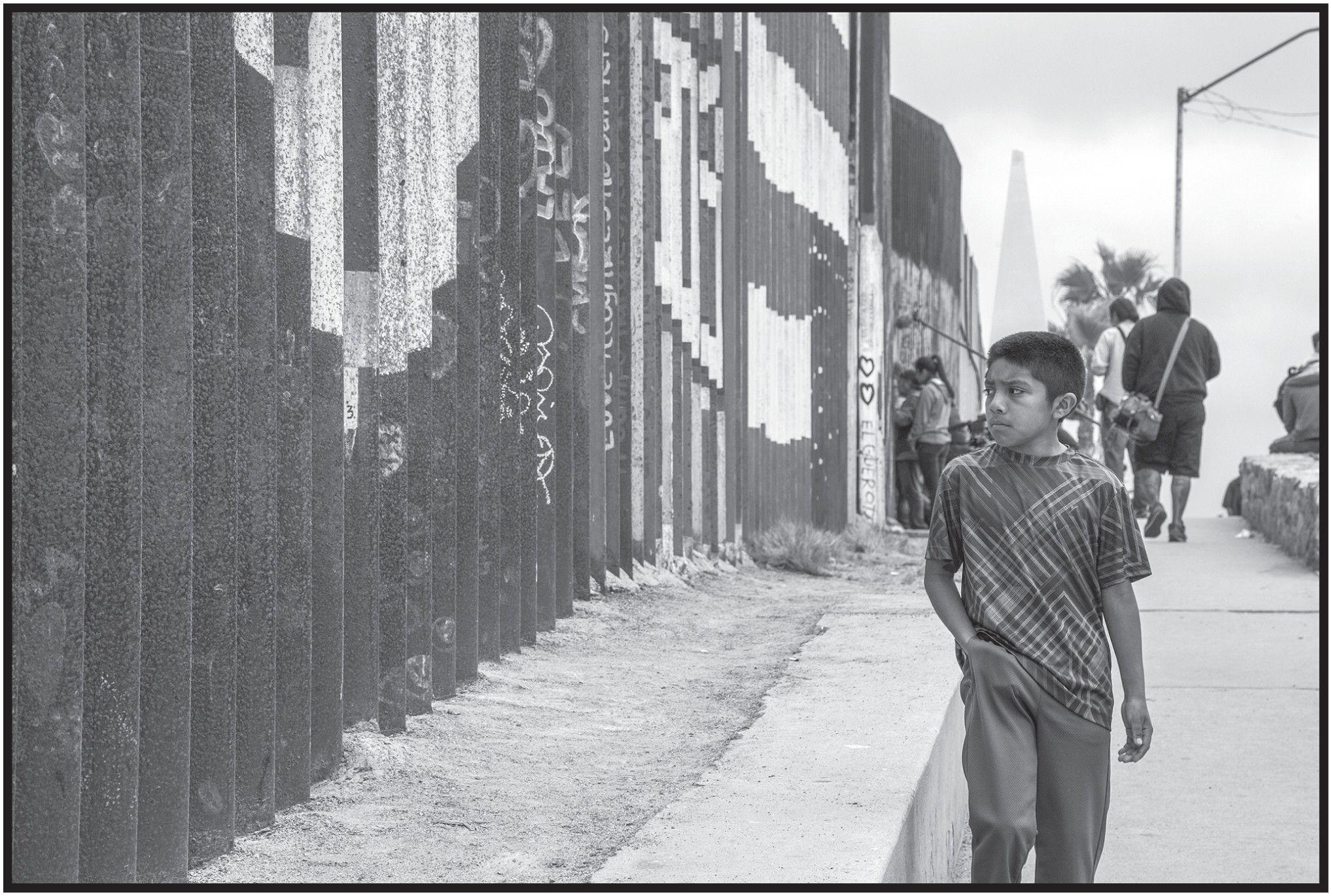

Talking about migration, at a time when the United States is implementing absurd actions—such as painting the border wall black—forces us to analyze the role of this wall and the logic of control that has guided US immigration policy. These policies have never sought to completely stop flows, but rather to make them increasingly difficult in order to maintain greater control over them.

Talking about migration means remembering that even before the physical wall began in 1992, an ideological wall already existed. This originated in 1848, with the establishment of the current 3,143 km border. Although at first it was an imaginary line, it already represented a symbolic barrier. The American conquistador displaced thousands of Mexicans, forcing them to choose between staying and becoming citizens of a country that did not respect them or returning to Mexico to retain their nationality. Many who stayed did so with the promise of being recognized as U.S. citizens; something that, in most cases, never happened. Since then, this invisible wall has been one of white

superiority, an ideology that has even contaminated people of Mexican descent, who deny their history and become as xenophobic as Trump.

To talk about migration is to recognize that this ideological wall deepened during the Bracero Program (1942-1964). Many Mexicans who worked legally began to feel superior to those who migrated without documents. This division among our fellow citizens sowed a wound that remains present in our communities, preventing unity in the face of a common enemy. Instead of uniting to confront racism, they divide, giving more power not only to Trump’s actions, but to an entire system of government that has always exploited them.

To talk about migration is to understand that the ideological wall was soon joined by a human wall. Immigration agents, with ever-increasing budgets and personnel, did not stop the crossings; rather, they regulated the flow of migrants to create the illusion of border protection. The role of these agents has never been to defend American society from a threat, but rather to ensure that citizens themselves do not become a threat to the government. They divert attention from the nation’s important problems and blame everything on the opposition and migrants, lulling the electorate into a false sense of security provided by the state, unaware that the state itself is the source

of their insecurity.

To talk about migration is also to note that, starting in the 1990s, construction of the physical wall began, beginning at the border between San Diego and Tijuana and later extending to a large part of the border. The goal was to facilitate the work of immigration personnel in detaining migrants, since in sections where there is no physical wall, the most lethal obstacle was left: the desert and nature. This wall of nature has claimed thousands of migrant lives, forcing them to cross through the most dangerous places, which in turn makes it easier for the Border Patrol to detain them.

To talk about migration is to understand that this physical wall has also moved south. In 2019, under pressure from the United States, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador deployed the National Guard to contain the caravans entering through Chiapas. Migrants were pushed to more dangerous routes within Mexico, leaving them at the mercy of organized crime, where they could be raped, kidnapped, extorted, and even murdered. And at the end of that terrible journey, upon reaching the north, they must face new risks before attempting the final crossing.

We cannot speak of full social justice while the debt to Mexican migrants remains outstanding, while migrants are not taken into account in the national debate and the country’s agenda.

To talk about migration is to note that during Joe Biden’s administration, the wall was extended even further south, reaching the Darien jungle on the border between Panama and Colombia. A barbed wire fence was placed on the least dangerous part of that border, forcing thousands of migrants to cross through much more deadly routes. Thus, the wall is no longer just between Mexico and the United States: it has become a continental policy of containment.

To talk about migration is to denounce that today Donald Trump continues his xenophobic rhetoric, using migrants as a scapegoat to sow fear in American society. While demanding the Nobel Peace Prize, he supports genocides like that of the Palestinian people, threatens to declare war on Venezuela, and fuels violence in Mexico and other countries, strengthening organized crime. We must not forget that the United States is the world’s leading consumer of drugs, and thanks to this, the cartels make unimaginable profits. This illicit money, in turn, enriches sectors of politics and the arms industry in the United States. Cartels invest millions of dollars in weapons purchases to defend their lucrative business and the Mexican military; while the gun companies, in turn, lobby and invest in politicians to defend their businesses.

To talk about migration is to realize that the biggest wall of all is the wall of indifference. Governments around the world have only paid attention to the migration issue during Trump’s second term, when he has used migrants as a political weapon. This visibility is not due to genuine humanism, but to pressure exerted from Washington. For them, migrants remain a bargaining chip: they take the hits, are discriminated against, never represented, and despite everything, they continue to send millions of dollars in remittances each year.

To talk about migration is to recognize that, thanks to Trump’s offensive, migrants now have the opportunity to demand that governments stop hiding behind empty rhetoric and take action. It is not enough to denounce Trump: it is necessary to point the finger at the global system, led by the United States, which has historically exploited the

poorest peoples.

To talk about migration is also a criticism of the Mexican government. Although poverty has decreased to unprecedented levels, the debt owed to migrants is just as large and important as that owed to Indigenous, LGBTQ+, women, and children—communities already served by the government. We cannot speak of full social justice while this debt remains outstanding, while migrants are not taken into account in the national

debate and the country’s agenda. The issue of return migration must be incorporated to prevent those migrants who return from returning to the place and situation that forced them to emigrate; rather, to return to a better Mexico, a place where people migrate out of choice and not necessity.

-

Let’s Talk About Migration: Trumpist Persection

Millions of women who have endured unspeakable violence on their migration journey are now being persecuted in the United States by an extremely xenophobic and misogynistic government, led by Donald Trump,

-

Culture | Labor | News Briefs

Workers Occupy Culture Secretariat, Demand 13% Wage Increase

2,000 workers have been receiving incomes below Mexico’s minimum wage for over two years.

-

People’s Mañanera March 2

President Sheinbaum’s daily press conference, with comments on electoral reform, the gradual move to a 40 hour workweek, employment, national security strategy, and once again, the call for peace.