Let’s Talk About Migration

This editorial by Diego Torres appears as the introduction to the November 2025 issue of Hablemos de Migración, a newsletter on migration issues published by the Frente Amplio de Mexicanos y Migrantes. We encourage you to subscribe. The English version of the November 2025 issue is available for download.

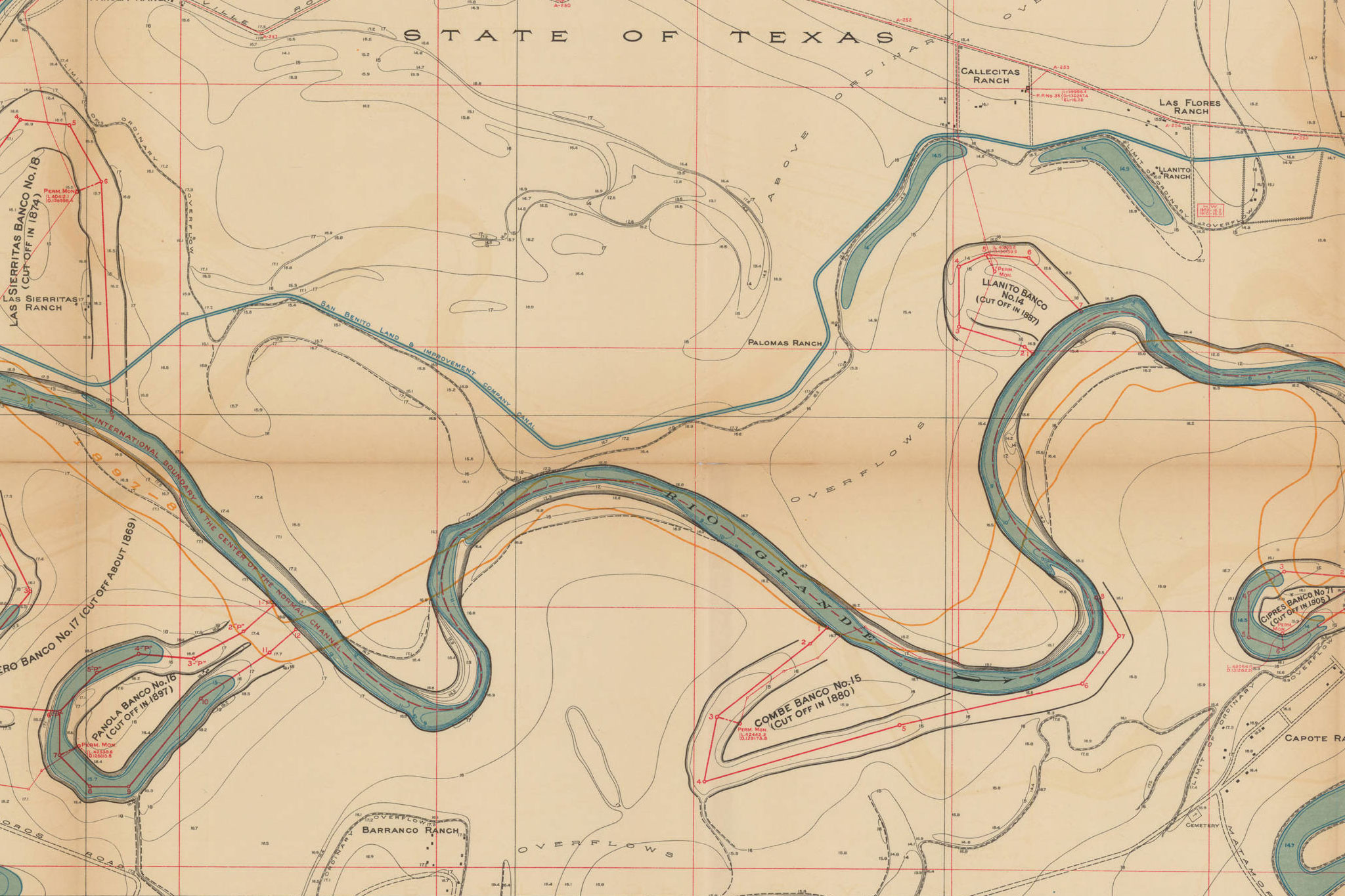

To talk about migration in November —the month in which Mexico remembers its departed— is also to reflect on the millions of men and women who have lost their lives in the pursuit of a dignified existence. Many died before even reaching the border, victims of organized crime; others perished in the desert or while attempting to cross the Rio Grande; and still others, already in U.S. territory, lost their lives working tirelessly, never attaining the dream that had driven them to migrate.

To talk about migration is to remember those who, through their labor, helped lay the foundations of the United States—receiving as their only reward the fate of dying far from the land that saw them born. The greatness of the United States did not come from its walls or its increasingly repressive immigration laws, but from the millions of migrants whose work was essential to its development. Yet that same country that profited from their effort refuses to acknowledge it, out of fear of losing votes to a misinformed electorate manipulated by an elite that exploits both migrants and citizens alike. The sweat of migrants has sustained the most powerful nation in the world, and still they are persecuted, despised, and criminalized.

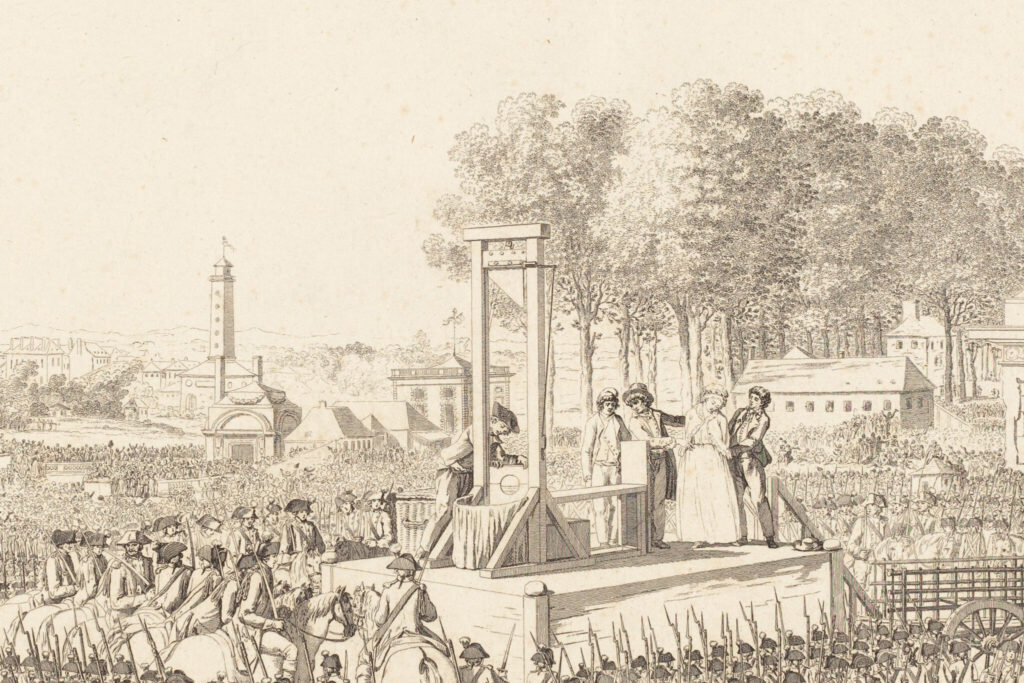

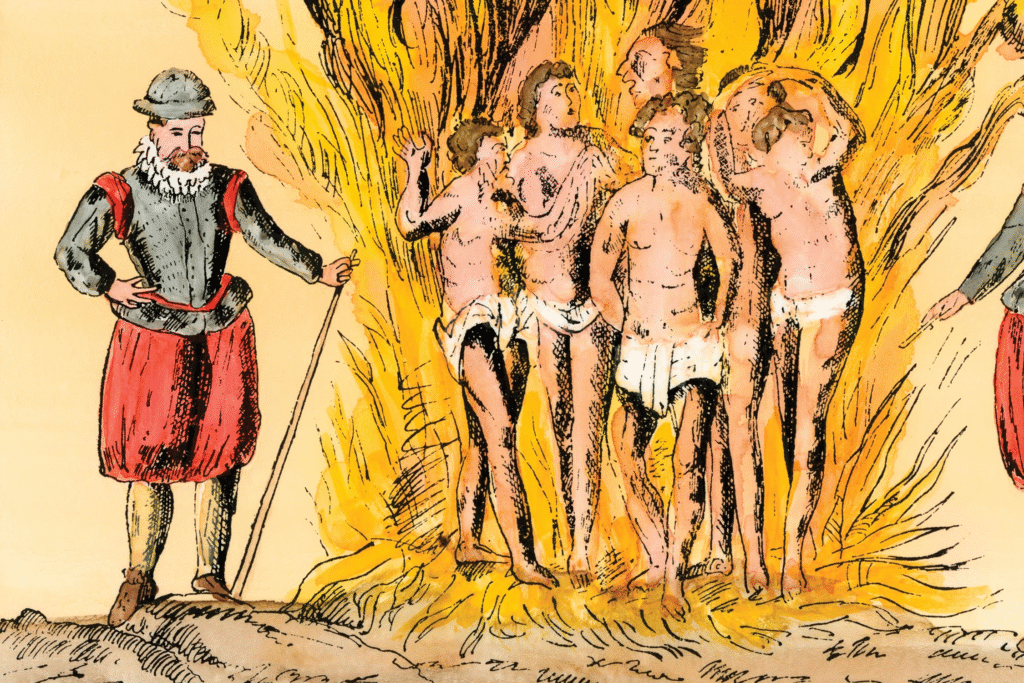

To talk about migration is to examine history: from the arrival of the first European colonizers— especially the Spanish and English—who violently seized foreign lands. Migration has always been marked by inequality. Those who invaded and plundered now call themselves “natives” and despise migrants, forgetting that their very presence was born of violent displacement, and that the growth of their nation has always depended on new waves of migration.

To talk about migration is to remember the hundreds of thousands of enslaved Africans who, against their will, became forced migrants. Torn from their homes, they were transported under inhuman conditions and forced to work without pay, rights, or freedom until death claimed many of them. Their labor, culture, and resistance are also fundamental pillars of the United States. Yet, centuries later, they continue to face the structural racism of a system that refuses to fully acknowledge their humanity and their legacy.

To talk about migration is to evoke the Chinese workers who arrived in the United States in the mid-19th century. Their labor was decisive in mining, agriculture, industry, and above all, in the construction of the railroads that united the country and made its economic expansion possible. In addition to being persecuted and humiliated by other migrants who called themselves “Americans,” thousands of them died as a result of the abuses inflicted upon them. That hostility was codified in the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, the first law to prohibit the entry of a specific ethnic group—a racist policy that still echoes through the U.S. immigration system today and has claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands of migrants throughout history.

To talk about migration is to recognize the thousands of migrants—many of them Mexican— who have died trying to reach the United States, from the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and the Bracero Program to the present day. They continue to be victims of organized crime, whether in the Darién jungle or on Mexican soil, as well as to the racism of armed groups such as the Minutemen or the Proud Boys, who patrol the border under the pretext of “defending” their country while turning the hunt for migrants into an act of hate. Added to these are those who die in agricultural fields, in factories or on the streets of the United States, lives that the authorities of both nations make invisible by pretending not to see the problem or even its existence.

To talk about migration is to recognize that these deaths do not belong only to the past. As long as poverty, inequality, and violence continue to force millions of people to leave their communities, the list of missing, abused, and dead will continue to grow. The tragedy lies not only in the journey but in the system that compels it—in the structural injustice that drives millions to seek elsewhere what they have been denied in their own land.

As long as poverty, inequality, and violence continue to force millions of people to leave their communities, the list of missing, abused, and dead will continue to grow.

To talk about migration is to denounce the lukewarm response of many governments to the xenophobic policies promoted by Donald Trump. During his administration, dozens of migrants died while in custody or while attempting to flee ICE agents. These deaths were not accidents or mere statistics—they were the direct result of a policy of hatred, indifference, and institutionalized dehumanization that still persists within large sectors of the U.S. government and society.

To talk about migration is to acknowledge that those who lost their lives seeking a better future may have found in death the peace that life denied them. Millions of migrants still live exploited, marginalized, or persecuted—and the most painful part is that many of those who persecute them forget that they, too, or their ancestors, were once migrants. The memory of those who are gone must serve not to repeat the mistakes of the past but to transform the reality in which migrants continue to die.

To talk about migration in this month of November, when we honor our dead and celebrate their memory, is also to renew hope. While many governments remain silent, millions of people— migrants and non-migrants alike—organize, march, and protest against authoritarianism and hatred. Their voices remind us that as long as there are those who fight for human dignity, the memory of migrants will remain alive.

-

Concessions, Concessions, Concessions

The yet-to-be-disclosed 200 mining concessions voluntarily returned to the Mexican state represent less than 1% of the 22,000 currently active, while questions remain about the government’s new strategy.

-

People’s Mañanera February 27

President Sheinbaum’s daily press conference, with comments on electoral reform, labour poverty, 80% of weapons seized originate in US, Sinaloa homicide reduction, and addressing root causes of crime.

-

Mexico’s Filthy Rich

Less than 8 pesos out of every 100 that the rich earn thanks to our collective effort returns to the economy in the form of investment. They are rentiers, clinging to their inherited fortunes, their connections to political & academic power & they extort the State when it threatens even the crumbs they refuse to give us.