Mexico City Public Works for 2026 World Cup Contradicts Needs of the Majority

This article by Eliana Gilet originally appeared in the January 26, 2026 edition of Desinformémonos.

With less than 140 days until the opening match of the 2026 World Cup in Mexico City, construction has taken over the city. All the spaces deemed “necessary” for the event are undergoing a cosmetic transformation, far removed from the needs of the majority of the population and, in particular, neglecting the long-standing urgent needs of the metro system. Faced with projects implemented without consultation and secret agreements between FIFA and the Mexican government, organized residents are demanding their right to “live with dignity in a city that welcomes and protects the people who have cared for it for decades.”

The area most affected by the intervention is the vicinity of Azteca Stadium. Vendors who had their stalls in front of the stadium bus stop were completely removed before the start of the year. Residents of the Acción Pedregales Cooperative—which, along with various organizations from the indigenous communities of Mexico City, San Lorenzo Huipulco, and Santa Úrsula Coapa, as well as Xochimilco and Milpa Alta, has consistently denounced the negative effects of the World Cup in Mexico—told Desinformémonos that when they resumed their actions under the overpass on January 4, the vendors were no longer there.

Furthermore, the construction of the bike path on Tlalpan Avenue, which links the Historic Center with the Stadium—covering 17 kilometers of the city, making it the main and most visible urban modification— has added to the protest the demands of various groups of sex workers from the Calzada.

“It’s the biggest project they’ve ever undertaken, and with so little planning. You can see how they make mistakes and correct them along the way. For example, when they first built the bike path, they realized there was no possibility of a bus stop at the stadium and had to redesign everything. So they removed the large planters because people had to stand on them to get onto the bike path. Since they’re constantly working on mistakes, we have even more uncertainty about what’s happening and what they’re going to do,” explained Natalia Lara in an interview with Desinformémonos during the assembly at the underpass on January 18.

“It’s been a dispute over public space in recent weeks, as the entire Santa Úrsula Coapa area is impassable,” Lara said. Rubén Ramírez, a traditional authority from the town of Santa Úrsula, emphasizes another key aspect of these projects: the lack of public consultation. “The construction being carried out around the Azteca Stadium is causing traffic and environmental chaos—in other words, general chaos—because there was no consultation. We, the people who live here, are the ones who know which areas are most affected and who are living with the consequences every day, but the authorities don’t care,” he asserted.

Contrary to this extractivism, the area surrounding the stadium has been developing into a meeting place where urban struggles against dispossession and the over-tourism of Mexico City are woven together. “Many comrades arrive every week, and their solidarity is the tool that allows us to continue, to keep going, and to see that results are emerging,” Natalia stated.

World Cup is just a Pretext

On Sunday the 18th, amidst the dust from the new construction at the stadium bus stop and trucks from the Federal Electricity Commission (CFE) claiming to be “laying cables for hospitals”—though neighbors suspect they were actually calibrating a new transformer recently installed on one of the stadium’s corners for the event—they had to negotiate the space. The first argument was early, to avoid leaving as the construction workers demanded; then, after 11 a.m., to ask them to temporarily stop making noise where the assembly was taking place.

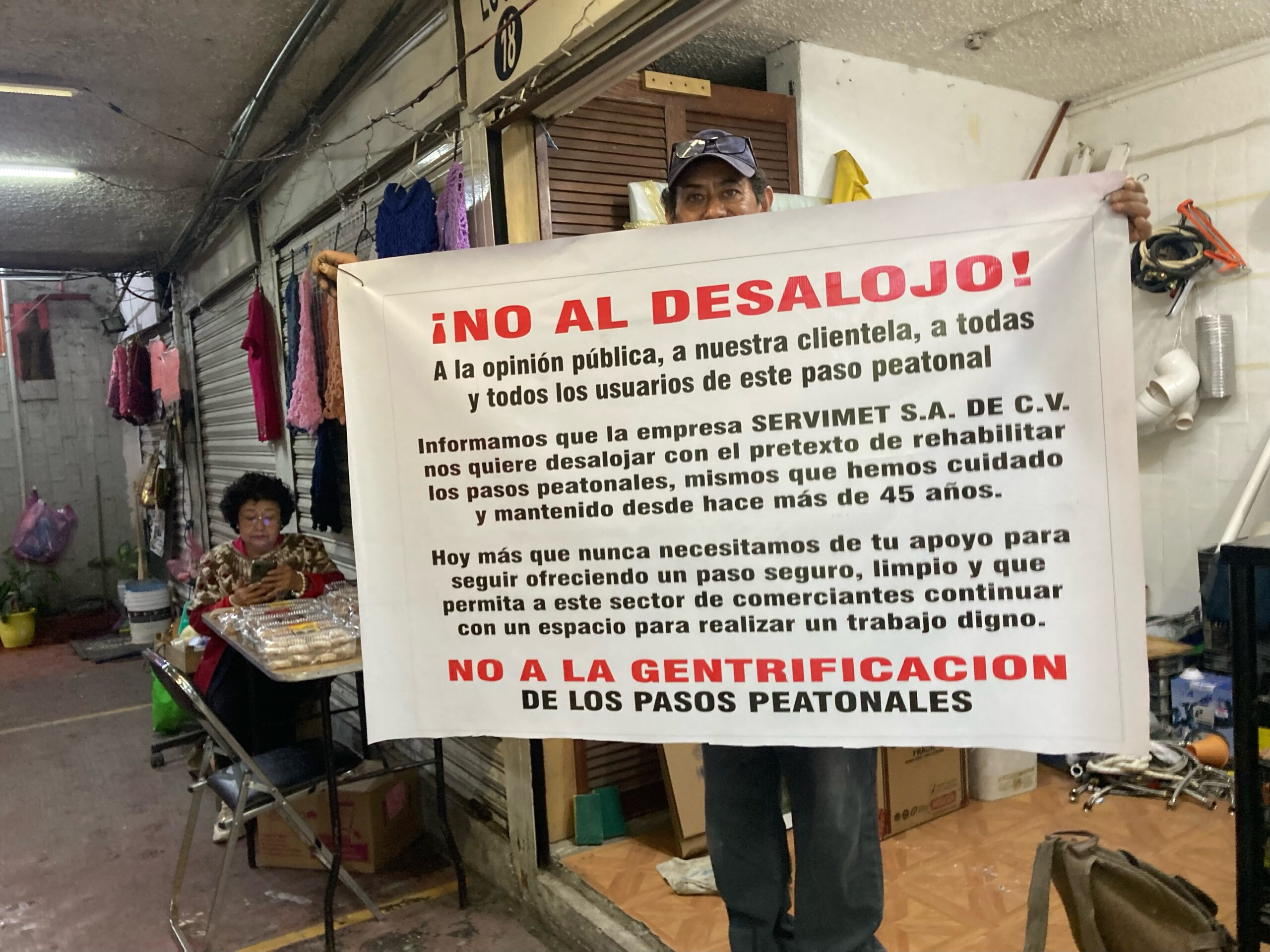

That morning, vendors from other underpasses arrived: the pedestrian walkways of Tlalpan who have been living under the threat of eviction for six months. “The government’s priority is the World Cup, but the consequences are serious, because it leaves many people without jobs. They try to make the avenue look really cool, but they don’t leave anything good behind. We approached the neighbors today to ask for their support, to ask for their help, because this isn’t right,” explained Mr. Ricardo Gutiérrez, who has been cutting hair for twenty years in one of the shops at the Tlalpan and Santiago pedestrian crossing.

The news reached them through Servimet, the metropolitan services office headed by Carlos Mackinlay, the former Mexico City tourism secretary, whom they directly accuse of trying to intimidate them into signing over their spaces. “He was very rude. In the meetings he held, because we are senior citizens, he treated us as if we were no longer capable of reasoning. He told us he would pay us 16,000 pesos for the space we have, in 16 monthly installments of 1,000 pesos! And with that, he would become the owner of the pedestrian walkways. It’s a ridiculous amount. Doesn’t he have any idea how expensive life is these days? There are people there with jobs,” the hairdresser complained.

There is indeed a whole world beneath Tlalpan Avenue in these pedestrian underpasses. Don Gutiérrez describes a situation similar to that experienced by the residents near the stadium: they took care of the area without the authorities paying them any attention, until the eviction notice arrived. “We’ve been a no-man’s land, but we took care of the place. We installed a submersible pump, electricity, and paint. We were the ones who provided services to the pedestrian underpasses so they would have lighting and people could pass through, interact with the businesses, and give us work. But when we suggest any ideas to the central government or the Benito Juárez borough, they don’t do anything. They’ll never do anything we need,” he complained.

The other members of Santiago 22 told Desinformémonos that only the pedestrian crossings in the Benito Juárez borough are still fighting, because those located in the Cuauhtémoc borough have already signed in favor of Servimet.

José Alberto Íñiguez, 65, who has worked as a tailor since he was 14, offers an important perspective on how the World Cup pressure affects local conflicts: “The World Cup is just a pretext, nothing more. They say the Koreans and Argentinians are going to be here… of course not! If they want to improve the uneven terrain, they can work at night, but the eviction is unfair,” he told Desinformémonos in an interview.

Since that Sunday, they have joined the neighborhood resistance that has been brewing under the Azteca bridge: “It’s unfair because we’re not taking advantage of this place, we’re simply surviving. But we’re not going to leave, we’re going to defend what our way of life means, nothing more,” said Don Alberto.

According to information provided to the press, the Mexico City government allocated 6 billion pesos (approximately 350 million dollars) for the “beautification” of Mexico City. This is the only fully known figure for how much public investment the World Cup has required for “its” venues. After the Azteca Stadium, the subway system has been the most heavily renovated, but far from addressing complaints about serious and obvious problems (the most recent, for example, on Line 4), public funds have flowed in other directions, such as the renovation of the Taxqueña bus terminal and the Auditorio station on Line 7, which has its entrance on Reforma Avenue, near the World Cup clock. Mexico City International Airport has also undergone extensive renovations to “improve” its everyday appearance.

The first light rail stations, those closest to Taxqueña, have also been closed for several months, forcing people to waste time accepting free bus rides to the first open station, Ciudad Jardín. “There are conflicts, internalized and normalized violence that we Chilangos (Mexico City residents) are already used to. What we have seen are complaints about the fare increase, because we see that all this infrastructure is being built to change public transportation, but they raise the fare, and FIFA isn’t going to pay anything,” Natalia pointed out.

According to journalistic work by Cuban reporter Penyley Ramírez, Mexico negotiated a complete tax exemption for FIFA during Enrique Peña Nieto’s presidency (unlike the agreements reached by Canada and the United States) and a substantial commitment of public investment to meet the needs of the private event. However, all official bodies have denied providing or even knowing about these agreements in response to public information requests submitted by the Acción Pedregales Cooperative.

“Last year, we requested the collaboration agreement with BBVA for financing the infrastructure projects through transparency laws, but the head of government responded that the agreement did not exist. Then we requested the general collaboration agreement from every agency we could think of, but each institution responded that they were not competent to provide it, and that is curious,” Lara noted.

While the World Cup and FIFA reaped abundant public investment for their private business, local residents complain that the environmental damage will remain on this side of the city once the tourists leave. They point out that flights will multiply in the city to facilitate connectivity between venues and host countries (10 percent more than the current 1,200 flights per day, according to Mayor Clara Brugada) in a highly polluted area like the Valley of Mexico. Around the stadium, construction dust has already caused respiratory problems for residents.

“We’re paying for all this infrastructure that’s being built, because FIFA isn’t going to pay a single penny to put on their show here. We’re the ones who always end up paying for this problem, because this isn’t the first World Cup we’ve experienced. We had the 1970 and 1986 World Cups here, and the local population, the indigenous communities of Santa Úrsula Coapa and San Lorenzo Huipulco, and the surrounding neighborhoods, never received any benefit. We’re still dealing with traffic chaos, environmental problems, and security issues, and now these events are going to add to that. They’re going to leave us with a mess,” Rubén declared.

-

People’s Mañanera March 9

President Sheinbaum’s daily press conference, with comments on US “anti-drug” militarization, new oncology hospital, International Women’s Day, electoral reform, and screwworm.

-

Mexican Politics & Gender Parity

Since 2019 constitutionally, and since 2025 in practice, Mexico is the only country in the world with parity of women and men in the three branches of government, writes Martí Batres.

-

Somos México: Old Salinas Supporters, Claudio X Supporters, TV Azteca Supporters, & PRIAN supporters

Neither left nor right so actually right, Mexico’s newest party Somos MX gathers together the neoliberal political detritus of other parties for one more kick at the can.