Mexico Rising: Under AMLO, a Sharp Left Turn

This interview originally appeared in our newsletter, México Solidarity Bulletin. We enocourage you to subscribe!

I must admit that I got teary-eyed and starry-eyed watching AMLO give his final El Grito, or battle cry, to defend Mexico’s independence and to honor its revolutionary heroes. From the palace balcony, he spoke to an enormous multitude of teary-eyed and starry-eyed citizens packed below in the zocalo. When he finished the traditional ringing of the bell and waving of the flag, he and his wife stood watching the fireworks display. Seeing them from behind in the video, framed by curtains, I wouldn’t have been surprised if they had flown off the balcony up to the moon!

AMLO’s six years will go down in history as a true “4th transformation,” a peaceful but decisive revolution that started a process of turning upside down Mexico’s social and economic pyramid. Who better than Edwin Ackerman to explain AMLO’s unprecedented accomplishments?

Over the last few years, we’ve interviewed activists who were not always happy with AMLO — feminists, families of the disappeared, independent labor organizers, Zapatistas. Their criticisms have basis in fact. AMLO had his shortcomings; he’s human — he can’t fly to the moon. He inherited a government with corruption baked in, and he had only six years to dismantle some of the structures that enabled it.

Now the responsibility falls to Claudia Sheinbaum. AMLO laid the foundation; she promises to build “the second floor.” And as AMLO says farewell, the Mexican people will shout his name, a well earned honor among the national heroes celebrated in El Grito.

Viva AMLO! Viva Mexico!

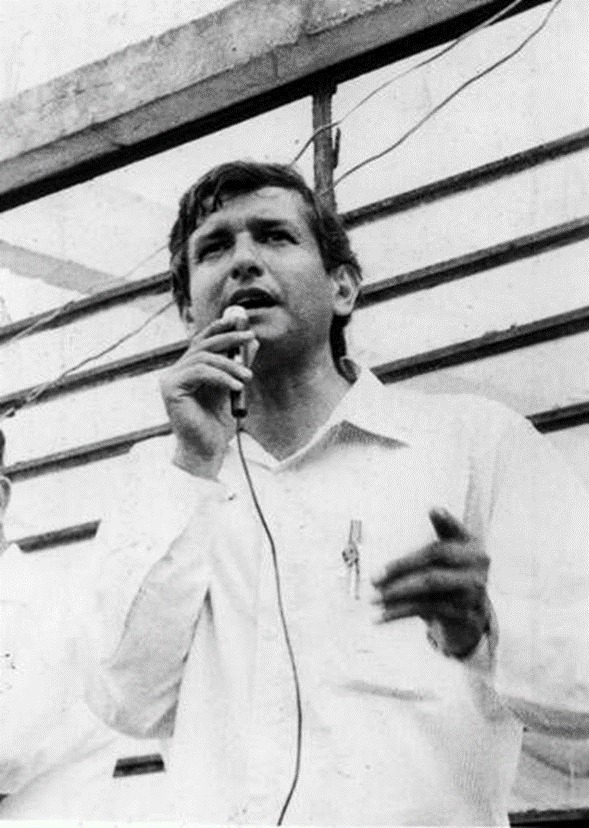

Tijuana born and raised, Edwin F. Ackerman is a historian who studies how political identities and parties are formed and how they work. Jacobin, NPR, Democracy Now, and other media outlets have sought his expertise. Now at the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at Syracuse University, he’s the author of Origins of the Mass Party: Dispossession and the Party-Form in Mexico and Bolivia. This analysis is expanded in his recent Catalyst article.

AMLO leaves office with an approval rating of almost 80%, and his successor and his party trounced the neoliberal opposition. What did AMLO want to achieve during his presidency?

AMLO envisioned his 2018 victory less as a change in government than as a transformative regime change. As he exits the political stage, is Morena’s growing electoral success due to the emergence of an entirely new social contract? Can the left consolidate the Fourth Transformation?

AMLO’s rise must be put in the context of the Mexican left’s trajectory during the neoliberal era. I want to make three broad points. The first is that the distinctive feature of AMLO’s project is how he reframed anti-corruption politics in a progressive direction. Second, he premised his actual policies and actions on a diagnosis of corruption as a specific neoliberal political economy — not as a series of isolated scandals or moral failings but a particular logic of capital accumulation that needed to be addressed as a system. Third, AMLO’s tenure is better understood as post-neoliberal rather than as a complete break from neoliberal policies — global free trade, for example — which are irreversible. He aimed to reshape the relationship between state and market in a society already deeply changed by decades of neoliberalism.

What were the failures of the electoral left during the neoliberal period, from the 1980’s to AMLO’s election in 2018?

AMLO’s administration is a late example of the “pink tide” governments that swept South America beginning in the early 2000s but had never reached Mexico. What was unique about Mexico that explains this?

The PRI ruled Mexico without interruption from 1929 to 2000. It didn’t maintain power only through fraud and repression. It also created a dense network of corporatist and clientelist relations, enabling it to co-opt emerging grassroots worker and peasant leaders. In other words, the sectors theoretically most prone to oppositional left-leaning mobilization were already organized under the PRI.

A Mexican Marxist thinker, José Revueltas, once explained that the PRI “can penetrate its organizational filaments all the way to the deepest layers of the population and thus impede the development of class politics.” As a consequence, Mexico’s left developed without a social base and without a coherent program.

The Left’s stunted development is perhaps best captured by AMLO’s own trajectory. His political path is entirely peculiar to twentieth-century Mexico. He doesn’t come from the socialist or social democratic left like his European counterparts. And he doesn’t come from militant union activism like Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva or Evo Morales in South America.

López Obrador was a PRI member and political appointee early in his career, when the party — the heir, after all, to an early twentieth-century agrarian revolution — still contained a strong progressive nationalist wing.

The PRI’s hard turn toward neoliberalism in the 1980s left the party’s nationalist wing isolated, eventually provoking a full break; those who left, including AMLO, then formed the center-left PRD party.

The PRI presided over a mixed state-market (public-private) economy. As the party consolidated power through corporatist arrangements, state enterprises and union leadership became synonymous with waste, mismanagement and corruption. Then in the 80s and 90s, the PAN party advocated for fighting corruption through dismantling public entities like the national oil company Pemex and opening up the economy to privatization and market competition. Those ideas propelled PAN to electoral victory between 2000 and 2012.

The PRD had limited electoral success; the most significant win was AMLO’s election as the mayor (governor) of Mexico City. When the PRD shifted right, collaborating with President Enrique Peña Nieto on major neoliberal reforms, AMLO left the PRD. He then led Morena, a coalition of social movements, to register as a political party In 2014.

So the Mexican people finally rejected the PRI in 2000 due to their disgust with state corruption; the private market seemed to be the answer. How did AMLO change the way that corruption was viewed?

PRI president Peña Nieto left office with the lowest approval rating on record — 24 percent. This dismal figure reflected, among other things, the widespread discontent stemming from a series of high-profile corruption scandals that came to define his administration.

Anti-corruption became the principal component of AMLO’s campaign and of his economic program. His campaign focused on three issues: ending corruption, regaining peace and using the state as an engine for redistributive economic policies. He saw these issues as fundamentally connected: corruption crippled the state’s capacity to energize the economy, and the growth of organized crime was a consequence of the abandonment of the redistributive role of the state.

Central to this understanding was his claim that neoliberalism was defined by corruption. As he put it in his inaugural speech, “I insist that the hallmark of neoliberalism is corruption. It sounds harsh, but privatization in Mexico has been synonymous with corruption. Political power and economic power have mutually fed and nurtured each other, and the theft of the people’s goods and the nation’s wealth has been established as the modus operandi.”

This view contrasts with the PRI/PAN neoliberal view, in which corruption was seen as synonymous with the large role of the public sector in the nation’s economy and the misdeeds of some bad actors there. But for López Obrador, corruption is not merely a series of individual crimes or isolated scandals; it is a consequence of the reconfiguration of the state-market relationship over the past decades. Corruption had become integral to a regime of private accumulation facilitated by the state.

Government officials siphoned off public funds through various mechanisms ranging from the outsourcing of government functions to the creation of parallel shell companies. A prime example was the sale of Telmex in 1990 to corporate magnate Carlos Slim, a close associate of then president Salinas de Gortari. These sorts of transactions turned state-owned entities into privately owned corporations, giving rise to an ultra-wealthy class.

Under the 2000 to 2012 PAN governments, even more boondoggle projects proliferated.

The independence bicentennial celebrations during Calderón’s administration are a notable example. The Estela de Luz, a hundred-meter-tall quartz monument, was inaugurated over a year late and cost three times its initial budget. A federal audit revealed overpriced construction materials and other irregularities.

AMLO’s linking of corruption and neoliberalism suggested that a solution required more than redesigning public institutions; it required reversing the state-market equation — in favor of the state. It is quite telling that AMLO’s cancellation of the Texcoco Airport project Peña Nieto had started differed from previous anti-corruption cases, in that it targeted a project symbolizing the systematic, large-scale transfer of public resources to private contractors.

So did AMLO replace neoliberalism with a new economic system?

A few months into his term, AMLO announced, “The neoliberal model, with its policies against the people, of stealing and giving away (public resources), is hereby abolished.” But in my view, the transition away from neoliberalism under AMLO — while significant — is moderate. His policies can best be described as “post-neoliberal.” That is, his reforms took place within neoliberalism, and they simply began to weaken or transform key tenets of neoliberal thought and politics. He began a process rather than instituting a new economic system.

AMLO reshaped the relationship between state and market in several ways. The flagship concept of AMLO’s government is “republican austerity” — a strategic adoption of neoliberal language used to combat neoliberalism itself.

This meant dismantling many private intermediaries between the state and the citizenry. Middlemen companies, NGOs, trusts (fideicomisos) and so on were awarded state contracts to deliver public services. AMLO saw these entities as opaque, redundant, expensive — bottlenecks for clawing back public dollars meant to be spent for the good of the people.

AMLO’s government also rejected privatization efforts. State-led infrastructure mega-projects like the Felipe Ángeles Airport, the Dos Bocas refinery, the Maya Train, a massive reforestation program, and more mark a break from PRI/PAN projects, which were often unnecessary and left unfinished. AMLO’s projects emphasize the importance of generating public-works jobs and economic development that strengthens local communities rather than displacing them.

AMLO’s administration has moved decisively to bolster the public sector’s relative power, particularly in the energy industry. It has increased tax collection from the wealthiest citizens by more than 200 percent. Conglomerates like Grupo Modelo, Elektra, Walmart and billionaire Carlos Slim’s companies are now under pressure to fulfill their tax obligations. The Financial Times described Raquel Buenrostro, then economic secretary, as an “iron lady” cracking a “whip on multinationals’ taxes.” These efforts yielded the financial means to expand the social benefit programs for Mexico’s people, “and first, the poor,” without raising taxes, which would risk alienating Mexico’s still important business sector.

Has AMLO set the stage for the growth of a new left based in the working class?

Working-class advances over the past six years have been startling. Real wages have surged by approximately 30 percent. The earnings of the bottom 10 percent of income earners have soared by 98.8 percent. Inequality has decreased. Over five million people were lifted out of poverty — the largest reduction in twenty-two years. But a rising standard of living alone is not enough to build a left.

AMLO restored the language of class in the political arena. His pride in his own modest rural background far from the urban elite and his jabs at fifis during his morning conferences contributed to his popularity. Among other things, it caused the electorate to become increasingly polarized along clear class lines. In the 2018 election, working-class support was dispersed across various parties, including those in the neoliberal bloc, while AMLO had significant support from middle-class professionals. But then, while in 2018, 48 percent of college-educated voters supported Morena’s congressional candidates, only 33 percent did in 2021. Conversely, support from voters with only elementary education rose from 42 percent in 2018 to 55 percent in 2021.

The loss of middle-class people’s support for AMLO is partly due to their symbolic demotion in his narrative.

While previous administrations valued cabinets of experts trained at elite universities, AMLO criticizes such technocratic expertise as political marketing and instead praises administrators for their closeness to the people.

Unlike AMLO, Claudia Sheinbaum is of the left. Compared to her, AMLO said, he’s bourgeois! What are the challenges to the left in power?

The neoliberal period in Mexico, as elsewhere, caused the growth of the informal sector, now between 40 to 60 percent of the Mexican workforce, and also increased its precarity. This has hampered the working classes from generating their own demands and elevating them to the political sphere, leading to a shortage of organized pressure from below to push the government leftward.

AMLO’s administration took over after a prolonged period of hollowing out the state, which impaired the actual implementation of new government plans. Without fully functioning governmental departments and public servants with sufficient experience and expertise, without state capacity, we can expect continued dependence on public-private partnerships and reliance on the military’s administrative apparatus to build and operate many infrastructure projects.

What are the dilemmas inherent in transitioning away from neoliberalism? Some include attempting to revive a welfare state with a deteriorated administrative apparatus, the contradictions of neo-developmentalist projects amid the looming climate crisis, the complexities of implementing progressive taxation during periods of stagnant growth, and the challenges of shifting away from a foreign investment–driven growth model. Consequently, the left’s story in twenty-first-century Mexico holds broad relevance, as these structural contradictions mirror the dilemmas the contemporary left worldwide faces.