Mexico & The Uncomfortable Proximity

This editorial by Edna Alcántara originally appeared in the August 5, 2025 edition of La Jornada, Mexico’s premier left wing daily newspaper. The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Mexico Solidarity Project.

Mexico is a free and independent country, where I was born and where I also learned that we don’t live in isolation, but under the constant watch of a vast neighbor with whom we have a long-standing relationship, one that over the years has become increasingly multifaceted and complex. It appears in street conversations, as well as in the highest spheres behind every major economic or political decision.

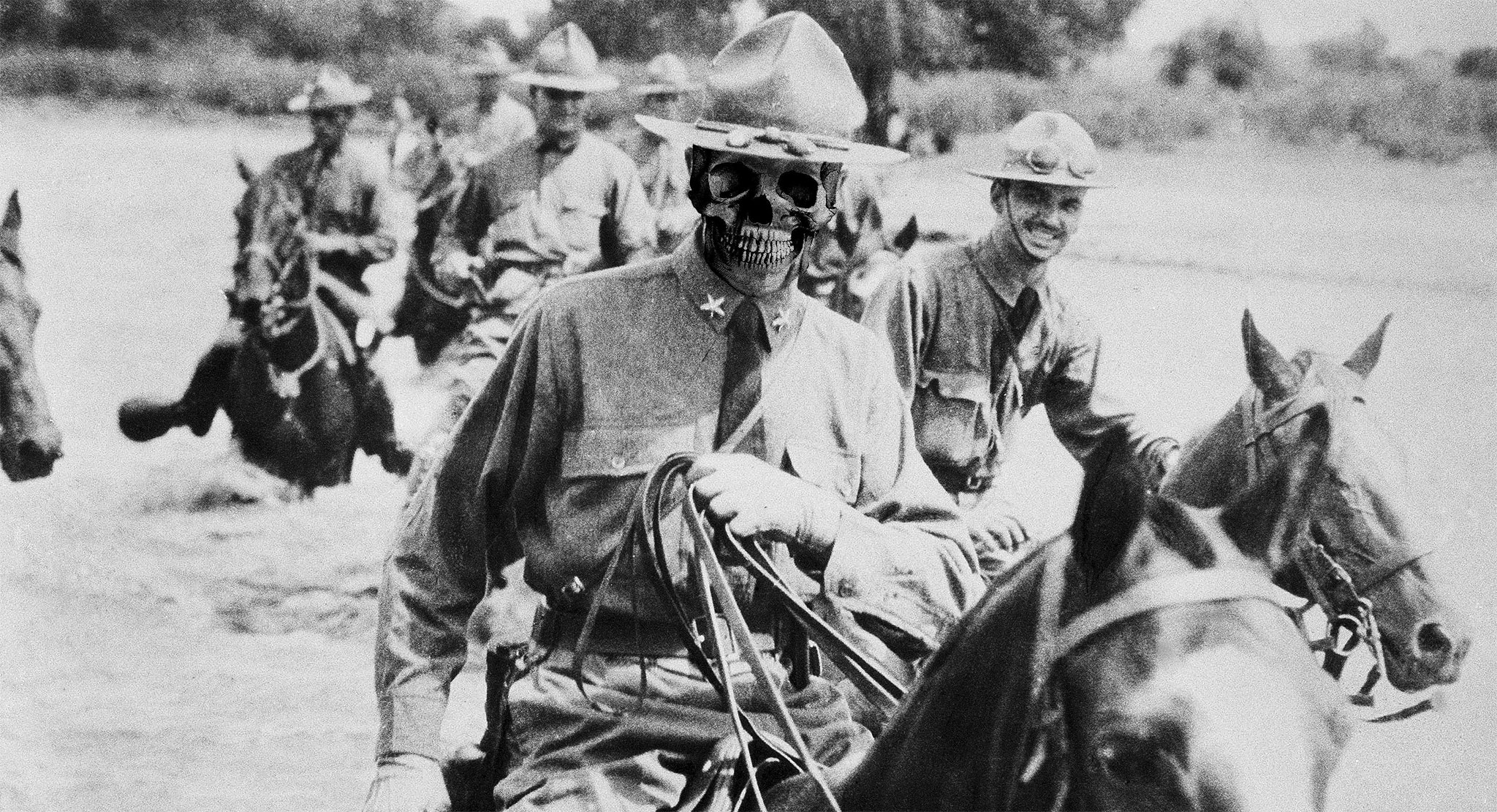

That reminds me of a phrase said by former President Porfirio Díaz Mori, who governed Mexico from 1876 to 1911: “Poor Mexico, so far from God and so close to the United States.”

Therefore, when our northern neighbor decides to implement important new measures, Mexico is always among those affected.

“Mexico is free, independent, and sovereign” is now a phrase repeated by Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum, echoing in every corner of the country. Mexico is a complex society, a miniature mirror of the entire world. But that doesn’t mean the world understands the problems we face, not even those of a single state, municipality, or small town.

The United States isn’t a distant country: it’s a constant presence. In everyday conversations, in newspaper headlines, in every public discussion, its shadow is always there, even attempting to interfere in Mexico’s internal affairs.

Gasoline theft is a major scourge facing Mexico, sometimes resulting in fatalities, such as the explosion at a Pemex pipeline in the state of Hidalgo in January 2019, which claimed more than 130 lives.

Even with the aggressive strategy to address this problem, hydrocarbon theft, according to experts, is prevalent in northern and central Mexico, surrounded by great speculation about the extent to where the criminal structures originate from in this crime.

Washington even hinted that “cooperation” is needed on this issue, as part of its agenda to address drug trafficking and organized crime, which the White House now labels as terrorist, and even offered to send troops to the border to combat cartels; but President Sheinbaum has been adamant: internal matters are resolved at home.

There are disputes not only underground. They also exist on maps. What in Mexico is proudly called the “Gulf of Mexico” has been renamed the “Gulf of America” in the United States. This is not just a linguistic detail: even in the sea we can see the shadow of hegemony and disrespect toward our southern neighbor.

If sovereignty reveals a historical tension, in economic terms that tension becomes transactional. In the reddish hills of Zacatecas, farmer Felipe Ruiz begins his day before dawn at the El Álamo ranch, where he painstakingly tends thousands of tomato plants. In the semi-desert of Fresnillo, his harvest is one of the most coveted on the continent.

This summer, I visited him with Adolfo Bonilla, his partner in the Agricola B15 Cooperative. His goal is clear: to export. But the fear of new US tariffs once again darkens the horizon. Hope and anxiety grow under the same sun.

The efficiency of the logistics chain is admirable: from the stem to the supermarket in less than 48 hours. In Texas, Arizona, and further north, the Mexican tomato is a daily fixture on many tables. But a single decree, a single signature, can shatter this delicate web woven over decades.

When the USMCA was signed, many, including American consumers, saw it as synonymous with stability and equity. Today, the reality is different: the agreement has become the starting point for negotiations; equity, a bargaining chip; the rules, tools of pressure. The bright red tomato has become trapped in the unbalanced logic of an increasingly transactional relationship.

On July 15, the U.S. Department of Commerce announced that imported tomatoes from Mexico will face a 17.09 percent tariff, because Mexicans offer the product at a lower price than U.S. producers, which affects the local market.

In international forums, Sheinbaum repeatedly emphasizes the importance of sovereignty and the need to build a multipolar world.

At the last G-20 summit, she bluntly stated that no country should impose itself on another. She proposed fairer cooperation mechanisms, where every country has the right to be heard. In the face of trade, diplomatic, and migrant pressures, Mexico does not seek confrontation, but rather asserts itself firmly to confront “with dignity, with pride, and knowing who we represent, which is our great people and this great nation we have,” the President emphasized.

August 1st marked the deadline for the US to impose new tariffs on its trading partners, including Mexico, which would further undermine the current international trade order.

Mexico and the US have been negotiating, but just as the deadline imposed by Washington for the new tariffs to take effect was about to expire, a 90-day extension was agreed upon with Washington.

Sheinbaum, who maintains that problems cannot be solved by imposing tariffs, is working on two fronts without going all out: she is proposing a strategy to her northern neighbor to reduce the US deficit with Mexico without affecting the Mexican economy, while on the other hand, she says she is focusing her efforts on strengthening the domestic market and trade with other countries with her Plan Mexico.

The current global geopolitical situation is undergoing profound and turbulent change, which in turn represents a historic opportunity to strongly consolidate integration. Against this backdrop, we saw the Mexican and Brazilian leaders hold telephone conversations last week to seek to strengthen and expand their cooperation in trade, science, and education.

We can’t choose our neighbors, but we can choose a new path of unity and strength with other Latin American and Global South countries that share our values to make us stronger.

-

People’s Mañanera February 9

President Sheinbaum’s daily press conference, with comments on scholarships, return of mining concessions, PRIAN exposed, Bad Bunny Super Bowl, and aid to Cuba.

-

8 Million App Users, TV Soap Opera Ad… & the PAN Still Can’t Find New Members

In Mexico, where political parties are currently publicly financed, the right wing PAN has spent a staggering amount during its lackluster recruitment drive.

-

Mexico’s National Film Archives Workers Demand Dignity

“Our struggle is legitimate; we are not asking for privileges or luxuries, only better working conditions and job security. We also seek dialogue. This situation has become unsustainable.”