Neither Equal nor Sovereign: The Politics of Fear

This editorial by José Romero, the Director of Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas, originally appeared in the July 27, 2025 edition of La Jornada, Mexico’s premier left wing daily newspaper. The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Mexico Solidarity Project.

One of the most persistent features of Mexican politics is the structural fear among its officials of contradicting, upsetting, or even misinterpreting the will of the United States. This is not an irrational fear or individual cowardice, but a learned and normalized behavior. It stems from history, is reinforced by economic dependence, and is reproduced in an elite trained under the logic of dominant power. What is said, left unsaid, or decided is frequently filtered according to what Washington can tolerate.

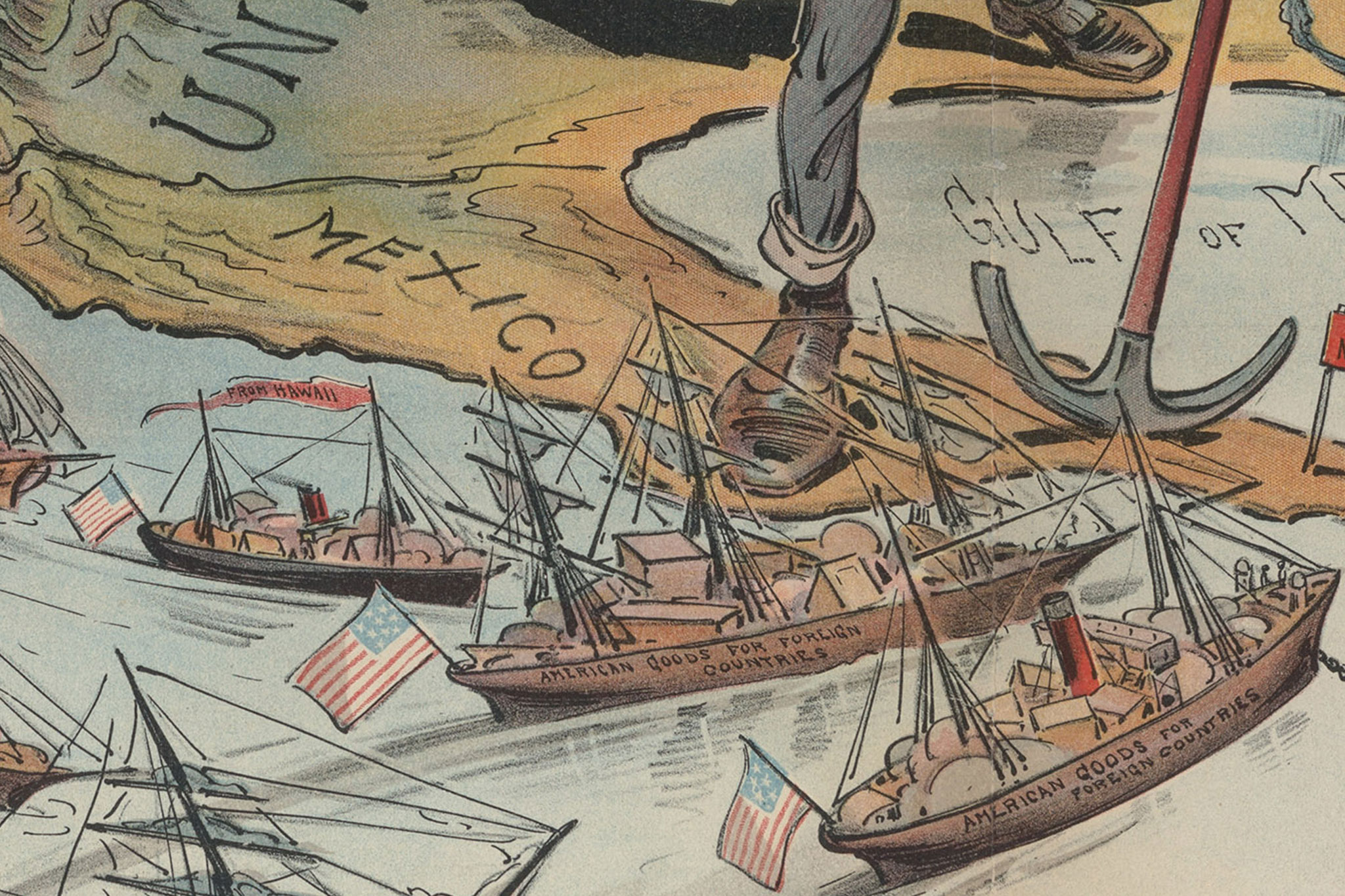

The roots run deep. After the 1846-1848 war, Mexico lost more than half of its territory and was marked by an unequal relationship with its northern neighbor. In the 20th century, this subordination was expressed from the occupation of Veracruz in 1914 to the pressures following oil expropriation of 1938. In the 1980s, the debt crisis placed the country under the tutelage of the US Treasury, the IMF, and the World Bank. It was the beginning of a sophisticated but limiting set of conditions.

Mexico anticipates and regulates itself: when it comes to the US, the country acts as if it has already been reprimanded, even before making a decision for itself.

NAFTA, signed in 1994, deepened this logic. Presented as an agreement between equals, in practice it inserted Mexico into North American value chains as a low-cost supplier. Today, more than 84 percent of our exports go to the United States, remittances reached $63.3 billion in 2023—4.1 percent of GDP—and 95 percent came from compatriots in the United States. More than 50 percent of foreign investment is American, and more than 70 percent of the banking system operates with foreign capital. This network of ties creates dependency: any gesture of autonomy is perceived as a threat.

In this context, trade or diplomatic retaliation doesn’t need to be implemented to be effective. Mexico anticipates and regulates itself. Expectation is enough. The country acts as if it has already been reprimanded, even before making a decision for itself.

But fear is not only economic. It is also expressed symbolically and culturally. A large part of the political and technical elite was trained in universities and multilateral organizations shaped by the United States, engendering an “academic colonialism” that imposes dominance not by force, but by intellectual legitimacy. Even those who studied in national institutions did so under the intellectual tutelage of professors trained abroad, heirs to foreign visions. If any official or analyst proposes a position that doesn’t fit with what Washington or the markets expect, they are considered naive or unprofessional. Alignment is no longer imposed from the outside: it is internalized, normalized, and becomes common sense. Thus emerges an elite that not only fears contradicting Washington, but cannot even imagine an alternative.

In this context, Mexican foreign policy has been reactive. It practices a “do not disturb” policy: neither to Washington nor to the markets, nor to international organizations. Decisions are not made for the good of Mexico, but rather to avoid inconveniencing external actors. And thus, sovereignty dissolves into the invisible margins of prudence.

A telling case in point was Trump’s 2019 threat to impose 5 percent tariffs if migration wasn’t curbed. In less than 48 hours, Mexico deployed the National Guard and effectively accepted “safe third country” status. There was no legal defense or consultation with Congress: just automatic compliance.

This logic persists. Today, the government faces new forms of coercion: tariff threats, security demands, pressure over fentanyl, agricultural restrictions, and international aviation rules. Under the USMCA, domestic decisions are evaluated externally based on presumed compliance. Cooperation is required, but negotiation almost never. Mexico continues to operate on the margins of fear, not self-interest.

However, there is room for greater autonomy. Mexico does not belong to military alliances or face sanctions, and it maintains diplomatic standing thanks to its neutrality. It has a geostrategic location, access to two oceans, a border with the world’s leading economy, and growing relations with Latin America, Asia, and Europe. The country has the capacity to diversify alliances and markets. What is lacking is not permission, but political will and institutions capable of sustaining its own strategy.

An industrial policy is needed as a genuine strategy for national productive transformation. This requires coordinating financial, exchange rate, fiscal, trade, technological, and capacity-building policies. Mexican companies must be at the center, with foreign investment in a peripheral and regulated position. The objective is to build a national productive apparatus with added value, skilled employment, and economic sovereignty. This requires a process of cumulative innovation through learning from the manufacturing sector itself. Mexican companies must learn to produce for themselves, master technology, and abandon external dependence. This is what has been missing for the last 43 years: a long-term strategy to strengthen our internal production, innovation, and technological autonomy capabilities.

A paralyzing fear persists: that of violating USMCA commitments or provoking temporary retaliation. Why continue to uphold the rules of a treaty that, in practice, is already dead? It was presented as a treaty between equals, but signed between deeply unequal countries. It has functioned as a legal architecture of subordination rather than a framework for cooperation. Today, it operates as an instrument of unilateral pressure. This fear inhibits any serious attempt to regulate or boost national capital.

That fear cannot be overcome with abstract discourse. It can be overcome with national banking, industry, and science; with universities committed to development and free from foreign tutelage. We need an elite that thinks from Mexico’s perspective, with a critical eye and commitment to the common good. Today, the political conditions, popular support, and institutional legitimacy exist to take that step. The change will not be immediate. It will require years, perhaps decades, but it must begin today. Today, facing a new political cycle, that decision cannot continue to be postponed. Sovereignty is not decreed: it is built step by step, with vision and will. Recovering it demands that we break the automatic reactions of fear and dare to think with our own voice.

-

People’s Mañanera February 9

President Sheinbaum’s daily press conference, with comments on scholarships, return of mining concessions, PRIAN exposed, Bad Bunny Super Bowl, and aid to Cuba.

-

8 Million App Users, TV Soap Opera Ad… & the PAN Still Can’t Find New Members

In Mexico, where political parties are currently publicly financed, the right wing PAN has spent a staggering amount during its lackluster recruitment drive.

-

Mexico’s National Film Archives Workers Demand Dignity

“Our struggle is legitimate; we are not asking for privileges or luxuries, only better working conditions and job security. We also seek dialogue. This situation has become unsustainable.”