Passing It Down

“I’m the proud daughter of a proud GM worker!” exclaims Esmeralda Jazmín Alonso Guevara, coordinator of Casa Obrera del Bajío. We don’t often hear this from young activists, even when they are already fighting the good fight for workers’ rights in their own workplaces.

In the third grade, my teacher asked us to write down what our fathers did for a living. My best friend, whose father worked in the same place as my father, looked at me doubtfully, but I was already writing down proudly, “mill worker.”

I never doubted then that as a worker in that loud, dirty lumber mill paying its employees minimum wage and no benefits, my father was as worthy as the farmers and ranchers and small business owners of my town. To be honest, more worthy! But I realized that later. I knew little then about his history before the mill job — his work as a labor organizer with the Communist Party, or the blacklists and McCarthyism.

My father once refused to participate in a so-called community improvement association, explaining to me that it consisted of ranchers and business owners. It was not in the interests of workers, and he wanted no part of it. He was clear about his allegiance, clear about theirs.

In the US, we may think we’re born with class consciousness and the will to fight, or that we only learn it in struggle. But when Esmeralda talks with such pride about her father at GM Silao, we’re reminded how powerful it is to also have family passing it down. In her daily work at Casa Obrera assisting workers build independent democratic unions able to negotiate better wages and benefits and working conditions, Esmeralda not only has the consciousness, she’s carrying on the work.

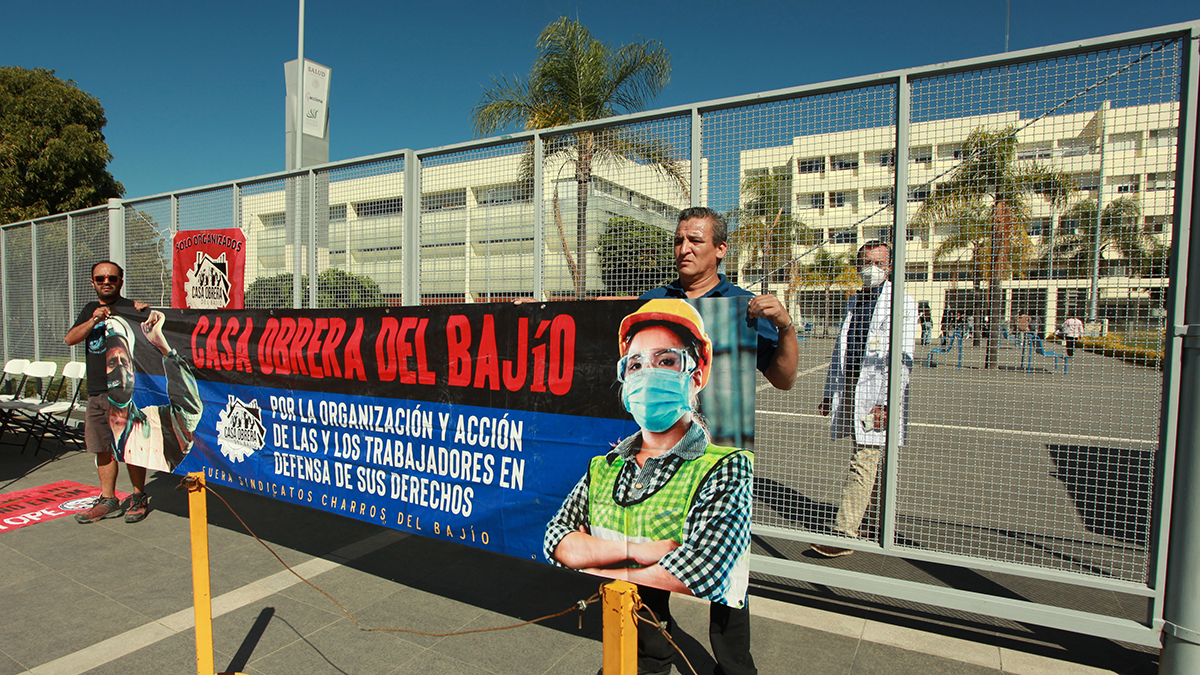

Esmeralda Jazmín Alonso Guevara currently serves as the coordinator of Casa Obrera del Bajío, where they organize to counter the historic attacks that capitalism has inflicted on Mexico. Born in the city of Silao, Guanajuato, Mexico, the proud daughter and granddaughter of farmworkers and factory workers, she has witnessed the transition of her home from farmlands to an industrial center. Alongside her father, a worker at GM Silao, she has joined the fight for authentic union representation and a society of equity, justice and collective good.

Did your father work at GM when you were a child? How did his work affect the family?

Before GM, he worked at a soft drink factory and then a shoe factory in León. His dream was to work at GM, which came to Silao in 1995, and he was proud when they hired him — that was 28 years ago. The salary was good; he had job security and health insurance. It improved our family’s life.

But since that time, things have changed. The CTM was the union from the beginning, and though the union representatives were workers, they were chosen by the union’s top brass, led by PRI representative Tereso Medina.

The CTM was and is known for its “protection contracts” — that is, it protects the company! The contracts prevent workers from protesting anything the company does. CTM delegates at GM became more and more corrupt as they came to understand how the union could benefit them individually, rather than all the workers collectively. They collaborated with GM — the CTM even had an office at the plant — and working conditions deteriorated radically. Benefits were cut; wages didn’t rise. Workers who didn’t go along were threatened.

So the workers began organizing to replace the CTM, right? They named their group Generating Movement, or “the other GM!” Was your father involved?

He wasn’t one of those who started the rebellion — GM fired the founders of Generating Movement. The company threatened and physically intimidated others; of course that frightened the rest of the workers. Alejandra Morales, who would become the future leader of the new union, was tracked down and got threatened at her home. If your children are in danger, it’s much harder to keep fighting. But Alejandra, a single mother, didn’t give up, and neither did other Movimiento members.

Even though we were all afraid, the organizing continued quietly, and my father joined the opposition to the CTM.

Fortunately for us, in 2019, the government passed new labor laws requiring workers to ratify their existing contracts. Also, the new USMCA trade agreement between Mexico, the United States and Canada took effect in 2020. It included a labor chapter that promised to enforce Mexican workers’ right to form independent unions.

It was still up to us to organize a “vote no” campaign and convince workers that a better union was possible. And with the company’s and CTM’s intimidation and dirty tricks, the fight continued to be tough. We lost the first election. But ballot boxes had been taken and “counted” by CTM. We had to file a complaint under the USMCA to get a new election. The second time, we won by a landslide!

Was that the most exciting moment of the campaign for you?

For me, it was when the Mexican government officially recognized SINTTIA as a legitimate union. We had to get 30% of the workers to join SINTTIA to register as a new union. When our union name and logo became official, it was a tremendously symbolic and motivating moment.

By the way, designing the logo wasn’t easy. From the beginning, equality between men and women at the plant was a really important principle. We wanted our logo to reflect that equality. Our first design showed a man’s and a woman’s raised fist. But the woman’s arm looked weaker! So we started designing again from scratch.

Although our commitment to gender equality was well known, it was still surprising that a woman, Alejandra Morales, was elected General Secretary. At first, it seemed incredible. But people voted for her because they saw her ability as a union representative. Over time, members — and the public and businesses! — are increasingly impressed with her leadership.

Casa Obrera del Bajío is a workers’ center linked to SINTTIA. Do GM workers go to SINTTIA or to Casa Obrera with a complaint?

SINTTIA has representatives on the factory floor. Workers can go to them for help, but with the intensity of production line work, they often don’t have time to stop and find a union representative. Instead, they can message the union with WhatsApp, and a union representative reads the message and reports the problem to the elected Executive Committee.

SINTTIA isn’t part of Casa Obrera, and Casa Obrera isn’t part of SINTTIA. We don’t interfere in SINTTIA’s internal affairs. However, both of us share the vision of authentic and democratic unions of, by, and for the workers.

At a key moment in SINTTIA’s struggle at GM Silao, CILAS, the labor research and advocacy center, formed Casa Obrera to provide support for workers without the resources to organize.

Since then, my team’s work has been to promote free and fair union elections, encourage workers to vote, and inform them of their rights. We support workers who wish to form independent unions. We don’t tell them which union to join, but we do encourage them to consider SINTTIA.

Currently, SINTTIA represents several factories in the automotive sector. What is its structure?

Each factory elects its own leaders. SINTTIA represents GM Silao, Frankische and Draxton, and we hope to add GM San Luis Potosi on June 27 when workers will vote on union representation. However, SINTTIA has open assemblies of its 6,400 members. We know that with this industrial structure, autoworkers have more power than if each factory has its own union. SINTTIA’s goal is to become a national union of autoworkers, like the UAW in the United States.

Are you hopeful that Mexico will eliminate the corrupt unions that work on behalf of the employers and for their own enrichment, and that the majority of workers will get to join democratic unions?

I’m the proud daughter of a proud GM worker! I’ve seen workers win and lose, but above all, I’ve witnessed their determination to fight for their dignity and rights. It remains an uphill battle. Even now, the CTM still has organizers inside the GM plant in Silao, causing trouble. It may not happen in my lifetime, but I have hope that one day the workers will triumph.

-

People’s Mañanera February 9

President Sheinbaum’s daily press conference, with comments on scholarships, return of mining concessions, PRIAN exposed, Bad Bunny Super Bowl, and aid to Cuba.

-

8 Million App Users, TV Soap Opera Ad… & the PAN Still Can’t Find New Members

In Mexico, where political parties are currently publicly financed, the right wing PAN has spent a staggering amount during its lackluster recruitment drive.

-

Mexico’s National Film Archives Workers Demand Dignity

“Our struggle is legitimate; we are not asking for privileges or luxuries, only better working conditions and job security. We also seek dialogue. This situation has become unsustainable.”