Plot of Complicity

This editorial by originally appeared in the January 19, 2026 edition of La Jornada de Oriente, the Puebla edition of Mexico’s premier left wing daily newspaper. The views expressed in this article are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect those of Mexico Solidarity Media or the Mexico Solidarity Project.

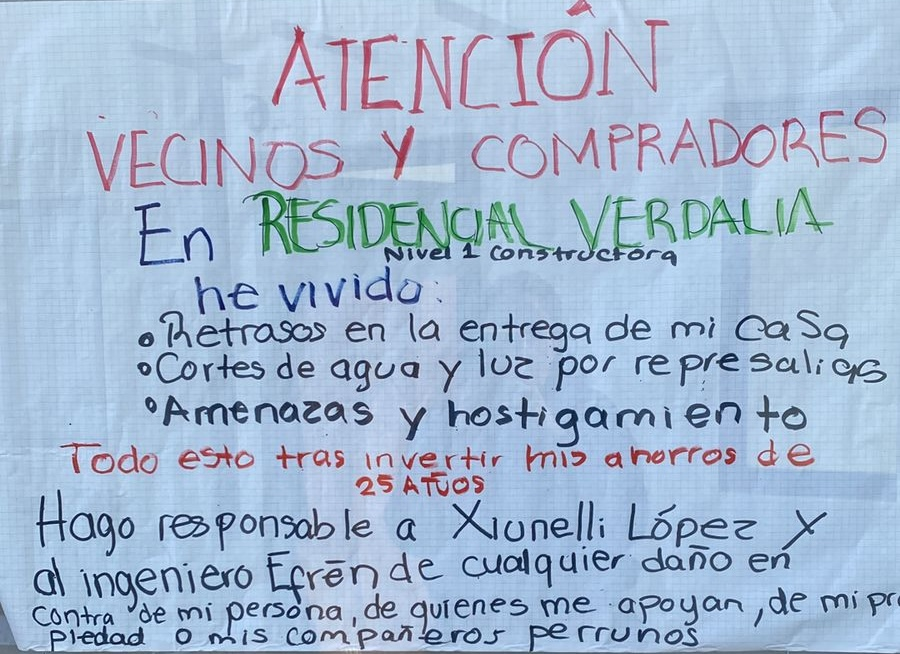

A problem has arisen in the Puebla real estate market that can no longer be explained as a series of isolated incidents, but rather as a sustained pattern of abuse met with inaction by the authorities. Industry associations readily acknowledge this: in urban areas, an average of five real estate frauds are committed every day. However, the institutional response remains minimal, fragmented, and, in practice, ineffective.

The Federal Consumer Protection Agency reports a mere 47 formal complaints for the past year, of which only 10 were substantiated. This figure is difficult to reconcile with the magnitude of the problem described by the victims themselves: breached contracts, homes not delivered despite verifiable payments, deposits not returned, construction halted without explanation, and unilateral cancellations without refunds. The discrepancy between social experience and official records is not accidental; it speaks to a system that discourages reporting and normalizes the suffering of those affected.

Those who go to the Public Prosecutor’s Office describe lengthy, confusing, and fruitless processes. The real estate companies’ systematic refusal to honor their agreements is met with prosecutors who move slowly or transfer the conflict to civil court without offering any real mechanisms for redress. In this bureaucratic labyrinth, time always works in favor of the fraudster.

There is no inter-institutional strategy to detect fraud patterns, warn consumers, or freeze operations of repeat offenders. Each case is handled—when it is handled at all—as if it were an isolated incident, without acknowledging that the damage is collective and systemic.

Even more serious is the official acknowledgment of inaction. In response to information requests, Profeco [Mexico’s consumer protection agency – editor] has admitted that it has not sanctioned any real estate company since 2020. Meanwhile, companies like Inmobiliaria Liguria, Promotora Sadasi, Ruba Desarrollos, Tertius, Ideas Aedificationem, and others accumulate files for fraudulent practices without any effective consequences. Having multiple open complaints doesn’t seem to be any impediment to continuing to operate.

The problem isn’t just the lack of punishment, but the absence of a preventative public policy. There is no inter-institutional strategy to detect fraud patterns, warn consumers, or freeze operations of repeat offenders. Each case is handled—when it is handled at all—as if it were an isolated incident, without acknowledging that the damage is collective and systemic.

Housing is not a minor asset: it represents assets, security, and a life project. As long as the State maintains only symbolic oversight and nonexistent sanctions, the message is clear: fraud is cheap. And in this vacuum, scams will continue to multiply, with total impunity, in plain sight.

-

Trump Will Not Take Our Oil

Venezuela’s oil belongs to the Bolivarian Republic. Mexican oil belongs to the people of Mexico. If the current administration decides to trade it with Cuba or any other country, it has every right to do so. Mexican oil does not belong to the US nor to Donald Trump.

-

Not By Bread Alone…

Returning to the Mesoamerican milpa agricutlural system could revitalize agriculture, while defending Mexicans and Mexico from a tangled, global necro-politics.

-

Socialism & Anti-imperialism in Mexico During the 1970s & 1980s

Widespread anti-imperialist mobilizations served as a pressure mechanism against the subservient and collaborationist policies of regional governments.