Protests Against AMLO’s Reforms Reveal the Strongholds of Mexico’s Ancien Régime

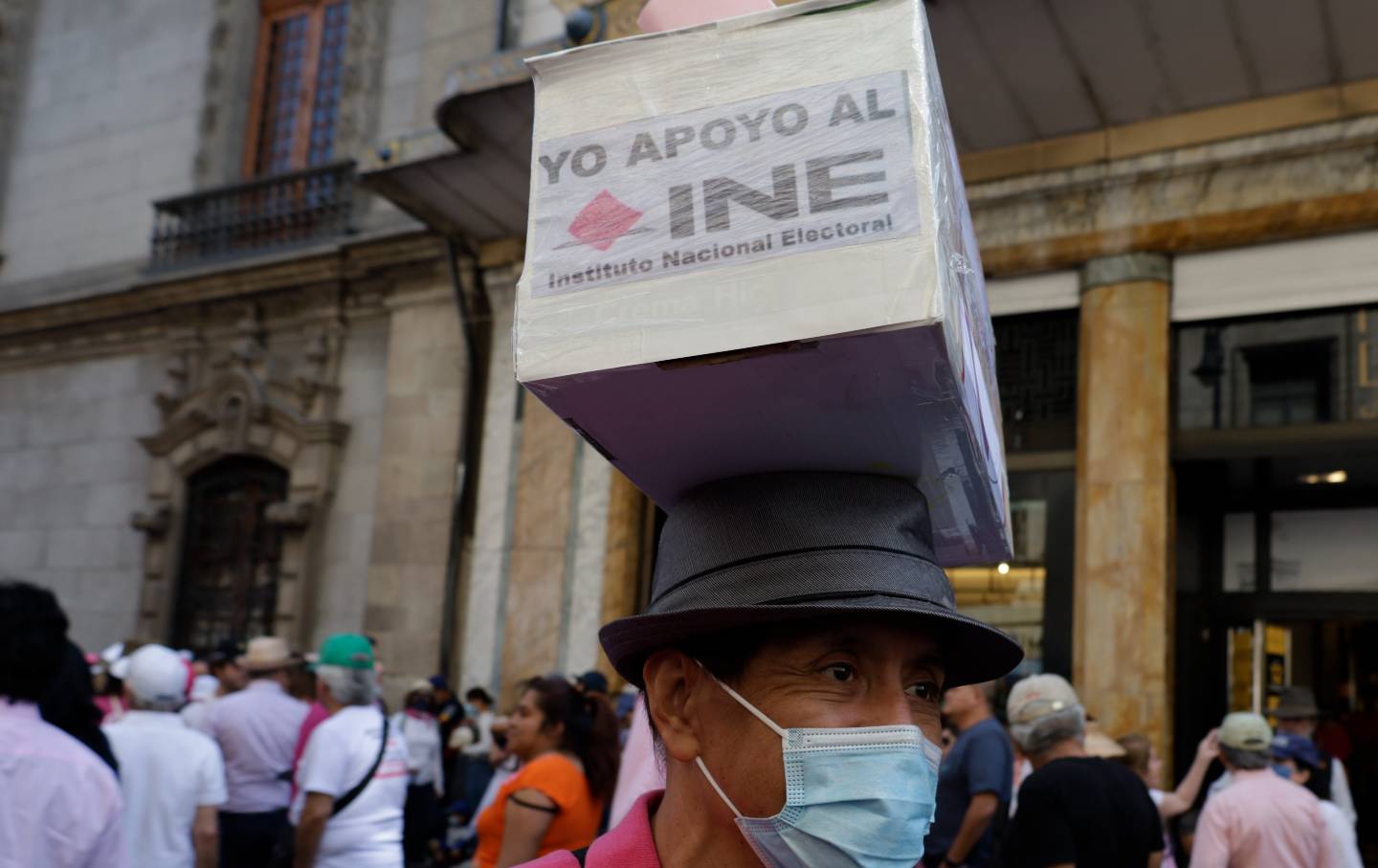

MEXICO CITY—The ongoing protests against Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s reforms to the National Electoral Institute, or INE by its Spanish acronym, must be understood in the context of the opposition’s declining sway.

During Mexico’s neoliberal period, the government was fully at the disposal of the country’s ruling class. With the election of López Obrador in 2018, that changed. Gone were the days where a small elite could count on controlling all the levers of the state to enrich themselves.

AMLO, as the Mexican president is often called, and his party, MORENA, not only won the presidency with a landslide victory. They also gained a majority in Congress and secured formidable political power, forming the first leftist government in the country’s modern history. Since 2018, MORENA has expanded its territorial reach, winning 12 of the 15 governor races in Mexico to control a total of 20 of the country’s 32 states.

Mexico’s political opposition—made up primarily of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) and the National Action Party (PAN), which alternatingly ruled the country for over 100 years—has seemingly been incapable of articulating a coherent response to this new political reality. Faced with an electorate that continues to show strong support for AMLO and his party, the opposition and the class forces behind it have taken refuge inside their strongholds within the Mexican state.

Unable to win over the population, the opposition is seeking to assert power and influence via other means—namely the INE, one of the country’s so-called autonomous institutions.

Under its previous iteration, the IFE, Mexico’s electoral authority allowed Felipe Calderón, the PAN’s candidate, to usurp the presidency in a 2006 election that was widely viewed as fraudulent by Mexican society. Despite strong evidence of vote manipulation and weeks of protest by AMLO’s supporters who contended that he had won, the country’s institutions allowed the fraud to be consummated.

Nonetheless, in the early years of AMLO’s presidency, he did not seek to reform the body. It was not until 202—when the INE canceled the registration of two of MORENA’s candidates for governorships—that the president turned his attention to the organization. Félix Salgado Macedonio in Guerrero and Raúl Morón Orozco in Michoacán were denied the ability to represent their party over relatively minor violations of electoral law. Inside MORENA, the decision was widely viewed as politically motivated, engineered to affect the party’s chances. The INE’s decision was viewed by the president’s supporters as disproportionate, especially in light of the INE’s tepid response to widespread illegal acts during the PRI’s victory in the State of Mexico in 2017.

The Mexican president and key figures in his party responded to this perceived slight by stepping up their criticisms of the INE—and in particular of Lorenzo Córdova, the head of the institute. One of the pillars of AMLO’s government has been what he deems “republican austerity,” and on the campaign trail he often repeated the slogan, “You cannot have a wealthy government and a poor people.”

Mexico’s electoral authority is among the most expensive in the region. Members of the governing council earn fabulous salaries—an average of US $14,500 a month, when most Mexican workers earn between $200 and $400 a month—with handsome benefits. AMLO has taken to calling it a gilded bureaucracy, with Córdova earning twice the salary of the country’s president. The original proposal called for a constitutional reform that would have changed many fundamental aspects of the body. However, MORENA was unable to secure the two-thirds majority required to pass the constitutional amendment in Congress. In light of that setback, the president and his party then moved on a reform that would only require a simple majority to pass, what has been deemed “Plan B.” This second proposal, which largely focuses on the reduction of spending through personnel cuts and some reorganization, was passed in quick fashion in both houses of Congress earlier this year. Contrary to the doom and gloom scenario painted by the opposition and some of the international press, nothing in the reform would undermine elections in the country or the INE’s autonomy.

The so-called “defense of the INE” has become the rallying cry of the opposition and its astroturf civil society organizations such as Mexicans Against Corruption and Alternatives for Mexico—led, respectively, by Claudio X. González and Gustavo de Hoyos, each of whom greatly benefited from his closeness with the country’s political representatives during Mexico’s ancien régime and now finds himself on the outside looking in.

Following the introduction of the constitutional reform, the opposition mobilized a sizable march in Mexico City on November 13, 2022. The march’s organizers worked to bill their event as a nonpartisan affair, having only one speaker address the crowd, former IFE president José Woldenberg. In response, López Obrador called for his own demonstration in the country’s capital.

If the opposition was feeling high after holding a successful rally, the pro-government demonstration shortly after surely dampened its spirits. An estimated 1 million people responded to the call to show support for the president. They waited along Mexico City’s Reforma Avenue under the hot sun for hours just to get a quick glimpse of the president, who walked the entire route before addressing the crowd assembled in the city’s Zócalo.

The opposition held a second rally to reject the president’s Plan B this Sunday, in the very same public square. This time, they rallied under the shadow of the recent drug trafficking conspiracy conviction of Genaro García Luna, a key figure in both PAN governments (2000–12). On Sunday, demonstrators quite literally gathered under a giant banner with García Luna’s face and the PAN logo, which was likely placed there by MORENA supporters ahead of the demonstration.

The PAN leadership has tried to distance itself from him, but since García Luna served as the public security secretary during Calderón’s term, which was defined by a security strategy that saw violent crime spike dramatically, it is unlikely that the public will believe that top officials did not know about his crimes. A recent poll found that 84 percent of the country want to see Calderón himself investigated for his alleged ties to organized crime.

Organizers also took less care to appear nonpartisan on this occasion, with figures such as the PRI’s Beatriz Pagés taking the stage and giving a highly one-sided speech. But despite successfully filling the city center, its unlikely that the opposition will be able to translate its mobilization around the “defense of the INE” into electoral victories.

The labeling of a leftist leader as a threat to the country and its democracy is a classic strategy in Latin America. The speedy approval of Plan B does open MORENA to allegations that future votes will not be “free and fair” or that results will be “unreliable.” In a worst-case scenario, fraud claims could lead to the application of sanctions by Washington, as it has done elsewhere in the hemisphere, especially with polls indicating that MORENA’s candidate will win the next election in 2024.

In his regular morning press conference on Monday, AMLO went to great lengths to link Sunday’s rally with business and political leaders from the country’s recent political past, alleging they were part of what he called a “narco-state” brimming with corruption. In the view of AMLO and his supporters, the real threat to the country’s democracy is represented by the opposition and the ruling-class forces who back it. As the country’s political transformation advances, political forces representing Mexico’s working-class majority must continue to drive the country’s political economic elites from the strongholds where they have taken refuge in order to move toward a more authentic democracy—where the country’s institutions reflect the majority and its priorities.