Solidarity, Greed & the State

This column by Alejandro Páez Varela appeared in the July 7, 2025 edition of Sin Embargo.

In addition to education and healthcare (and energy, in the Mexican case), societies will increasingly decommodify more sectors in the future. I believe public services should follow suit. Water shouldn’t be a commodity, but neither should energy, the internet, or public safety. Services shouldn’t be subject to market forces, just look at what happened in the United States or Spain with electricity during times of climate stress. That’s what this article is about. And it touches on the case of three social predators: Diego Fernández, Salinas Pliego, and Germán Larrea.

In October 2019, the mayor of Colón, Querétaro, Alejandro Ochoa Valencia, announced that he was attempting to collect one billion pesos that Diego Fernández de Cevallos owed the municipality because he had failed to pay the corresponding taxes, just as the PAN made him a presidential candidate.

I can guess what happened next: Diego picked up the phone, yelled at the mayor, and intimidated him with a storm of legal jargon that sounded like the fury of hell itself. Of course, he made the poor president of a rarely mentioned town regret even being born and granted him a 971.8 million peso property tax discount. The former senator paid a mere 12 million 763 thousand pesos for 16 years without meeting his obligations for Villas del Estanco, a 220-hectare ranch. Any of us would have lost our property and our freedom. Fernández de Cevallos, on the other hand, the personification of total political power, overcame the episode in secret and with multimillion-dollar profits.

I imagine the former PAN presidential candidate must have thought about countersuing the taxpayers; forcing them to pay him the billion pesos they were trying to charge him, and something extra for his trouble. Lawyers close to the PAN and the PRI have done just that; they’ve extracted billions of pesos from the Mexican state in this way. Besides, “‘El Jefe’ Diego” (as they call him) would think that since he met every Monday and Tuesday with Carlos Salinas and was at the pinnacle of power, he was immune to tax obligations. I don’t know. I suspect we’ll never know. But it’s an interesting fact for anyone studying the ethical behavior of the Mexican political and business classes.

It seems to me that the Diego Fernández case is not at all different from the Ricardo Salinas Pliego or Germán Larrea cases. In fact, the evolution of the fortune of the owner of Grupo Elektra is very similar to that of the owner of Grupo México. Both have done extraordinarily well since Andrés Manuel López Obrador came to power due to a combination of factors, including responsible management of the Mexican economy, undeniable negotiating skills with the United States (Donald Trump or Joe Biden), and even luck. All of this combined has made Mexico, in recent years, the largest trading partner of the world’s largest economic power. No more, no less.

Salinas Pliego’s fortune, as I explained in a previous post, is declining, while Larrea’s is growing slowly but remains very high. According to Forbes, it was worth $13.8 billion in 2017; by 2022, it had reached $30.8 billion—double that amount. Right now, Larrea and his family have $28.6 billion.

The big question, in all three cases, is what makes them so mean; why are Diego, Salinas Pliego, and Larrea incapable of doing even the smallest of citizen-to-citizen efforts (paying their tax obligations) when they’ve made a fortune at the expense of the state, through concessions, or through power relations? All three have received tax write-offs, and of course, the case of the owner of Grupo Azteca is the most dramatic (due to greed) because it will end in tragedy for his companies, but it’s no different from the previous ones.

Since so-called “social democracies” have often been a complete failure, people are suggesting that it may be time to go further, talking about decommodifying economic sectors that directly impact social life and contribute directly to inequality

What drives a man as rich as Germán Larrea to refuse to pay for the cleanup of a river he polluted while extracting wealth that belongs primarily to the people he’s harming? Is it simply greed? What drives him not to donate a meager, well-equipped hospital when he has millions of dollars to spare, should he so choose? The Fourth Transformation has allowed him and other big businessmen to strengthen their fortunes without evading their taxes. Why not be socially supportive? What’s stopping them?

Since so-called “social democracies” have often been a complete failure, a group of philosophers, historians, and economists is suggesting that it may be time to go further. They are talking about decommodifying more economic sectors that directly impact social life and contribute directly to inequality.

Let me explain a little further.

During the 20th century, many societies shifted toward the center from the right, and even toward the center-left, when they realized that public policies could be enough to eliminate inequalities without having to resort to the “communism” that so frightened the West. The United States had Franklin Delano Roosevelt, for example, who, incidentally, spent more than a decade in the White House; Labour took power in Great Britain, and throughout Europe, governments that listened to unions and labor unions grew. We ourselves experienced a social uprising (the 1910 Revolution) that became a government, and we had my General Lázaro Cárdenas del Río.

This trend led to the decommodification of two sectors in particular: education and health. We Mexicans can fully confirm, as can Americans and Europeans, that taking schools and hospitals away from corporations and entrepreneurs and placing them in the hands of the state works. Millions of citizens have benefited for generations from having public institutions that took care of our health and provided us with free education.

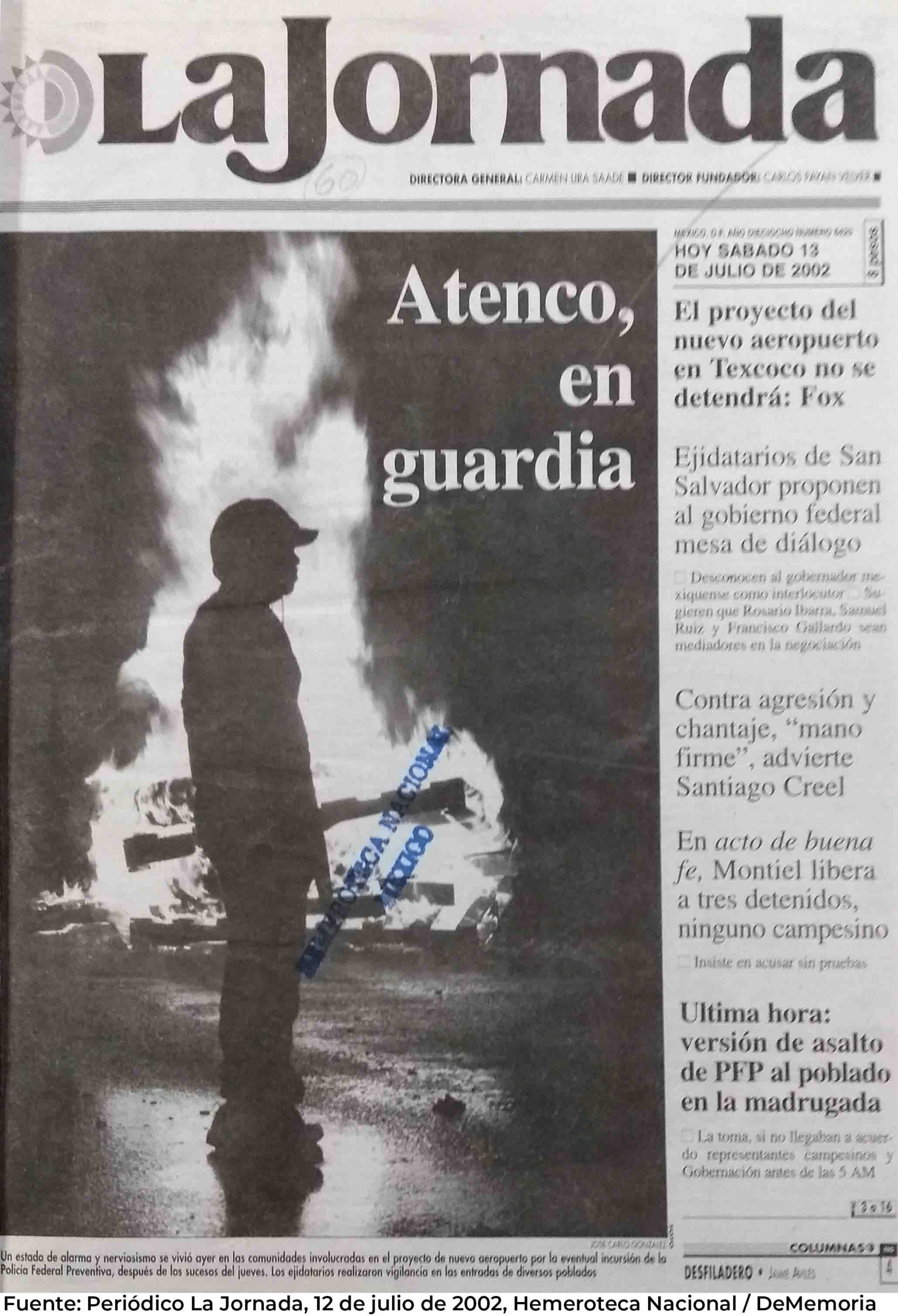

Then came Carlos Salinas de Gortari, Margaret Thatcher, and Ronald Reagan, and a social counter-reform, called “neoliberalism,” was launched to strip the middle and lower classes of their achievements. Education and healthcare were opened to private interests to the extent possible, and politicians only stopped when there was popular resistance. I’ll give an extreme example that speaks volumes and reveals its importance today: Atenco.

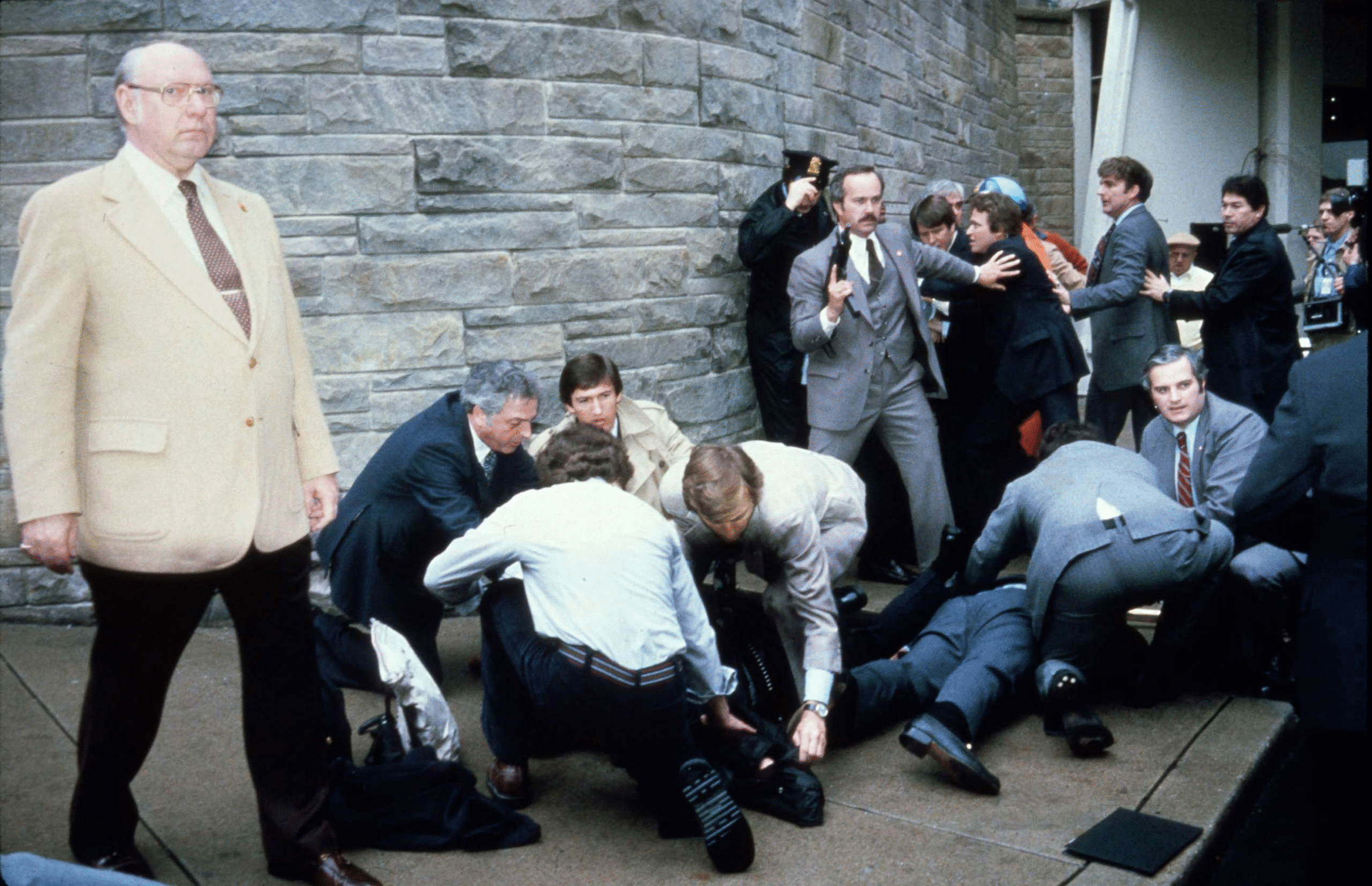

A people oppose the seizure of their ancestral lands to build an airport, and the state rapes their women and tortures and imprisons their men, children, and the elderly. It was Vicente Fox and Enrique Peña Nieto, let us not forget. Those small but significant resistances were what prevented the right-wing counter-reform from privatizing everything. Here, and around the world. There are similar examples in Great Britain and the United States.

Neoliberalism didn’t just want to commodify education and health: it wanted to commodify everything, including energy, water, ancestral lands, the sky, the air—everything—despite the fact that one of the most effective ways to guarantee social mobilization (basically, escaping poverty) has been by guaranteeing education and health to vulnerable populations.

Social counter-reform continues (the Donald Trump case will be a subject of analysis for a century) and has been carried out in a wide variety of ways; sometimes it was brutal, as in Atenco or the mining towns of Great Britain; other times it was belated, such as the recent mistreatment of the elderly by the clown Javier Milei in Argentina; and often it was barely perceptible, such as handing over small pieces of Pemex to private companies while simultaneously draining it of fresh resources.

However, hundreds of millions of people around the world now understand more than ever before in history that sectors like education and health care must not be commodified and always depend on the state. This is a tremendous achievement. It’s a huge social advance that people understand that there are sectors that simply cannot be handed over to businessmen because the Larreas or Salinas Pliegos will always be there to extract profits from the people, even if there aren’t even any people left.

Now think about this: what would happen if we decommodified other sectors besides education and health (and, in the Mexican case, energy as well)? I believe that, in the future, this will happen; that societies will realize that it’s the best course of action, and then it won’t be as frightening as it is now. With which other sectors do we begin a deeper process of decommodification? That’s the big question.

Some believe that, naturally, culture should be a right of citizens and an obligation of the state. And it can and should provide resources and jobs, as is the case in Italy, where it has become one of the main drivers of the economy and the anchor of another powerful sector: services (hotels, restaurants, tourism, etc.). Which sectors should be decommodified?

I believe we must immediately decommodify public services. Water shouldn’t be a commodity, but neither should energy, the internet, or public safety. Services shouldn’t be subject to market forces, because look at what happened in the United States or Spain with electricity, during times of climate stress. Almost all companies are companies: if you climb on their backs, like scorpions, they’ll sting you.

And then, I feel, both urban and rural mobility must be completely decommodified. As I say, people are much more aware today than they were a hundred years ago, when free healthcare and education are the minimum a state should provide to ensure a fairer distribution of national income. This trend should expand to other sectors. We should, at the very least, encourage this debate.

Salinas Pliego, Germán Larrea, and many others equally or more selfish leave important lessons for Mexico’s recent collective experience. One of them is that they are petty, period. They have no social dimension, and it’s difficult for them to acquire it. It may even be the opposite: after obtaining enormous benefits from the state, they demand more, no matter the conditions. They are slaves to money.

Both of them, like many others, are bad employers. The first claims the jobs he creates as if he didn’t get any benefits from each worker, and the second is simply an exploiter who doesn’t share any profits. And if anyone wants to debate that with me, just tell me how many miners they know who live well.

However, the State should do nothing against them. They should only comply with the law, and if they don’t, correct it. I think President Claudia Sheinbaum’s response is the correct one: you don’t pay taxes, you don’t have contracts. Shout all you want because you have the right to do so, but you won’t have any of the perks you demand from the government; the ones you’re used to.

Salinas Pliego has taken his rudeness toward the President so far that I, perhaps, would have acted very differently. Comparing a woman of Jewish descent to a Nazi criminal isn’t something you see every day, and her response with such calmness and maturity elevates her to another level.

Claudia shares lessons that many should learn, starting with Diego Fernández de Cevallos, an overrated, conceited, rotten-hearted little fellow; with political offspring scattered across the country and with fewer and fewer opportunities to return to power, thank God.

-

A Circus at Mexico’s Education Secretariat

The dispute is not a fight for the defense of public education, but a brawl between rival power groups for control and the collection of political rents from a pedagogical project that has not yet been born.

-

A Bigger Plan

López Obrador’s fear of Mexico’s abrupt return to the right still applies today. The Brazilian case is instructive.

-

Mexico Needs a Macroeconomic Policy for Growth, not the Finance Sector

While the Mexican government attempts to curry favour to receive preferential treatment in USMCA negotiations, it ignores the fact that the Trump administration violates all established international norms and makes decisions only based on US interests.