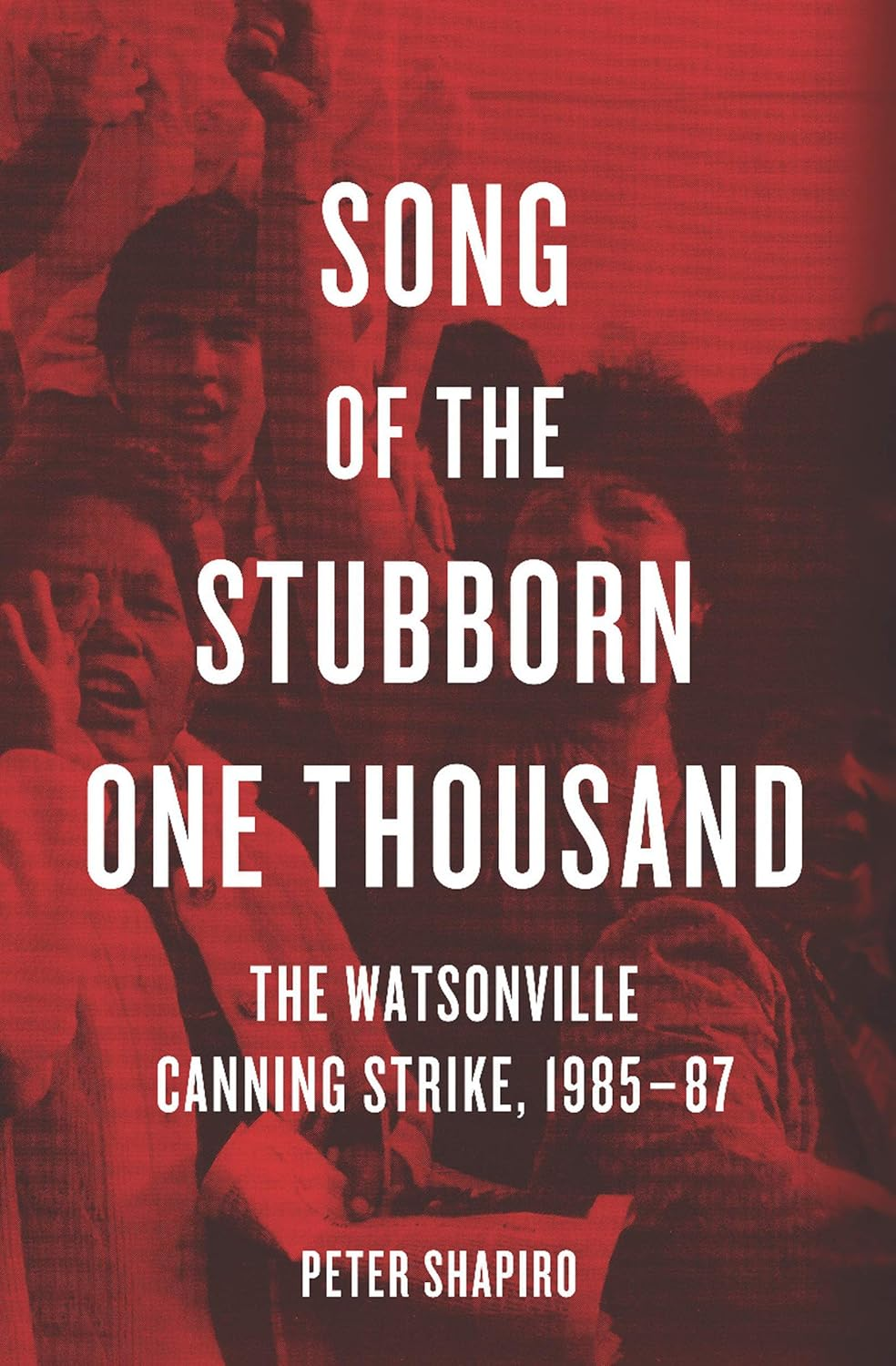

Song of the Stubborn One Thousand

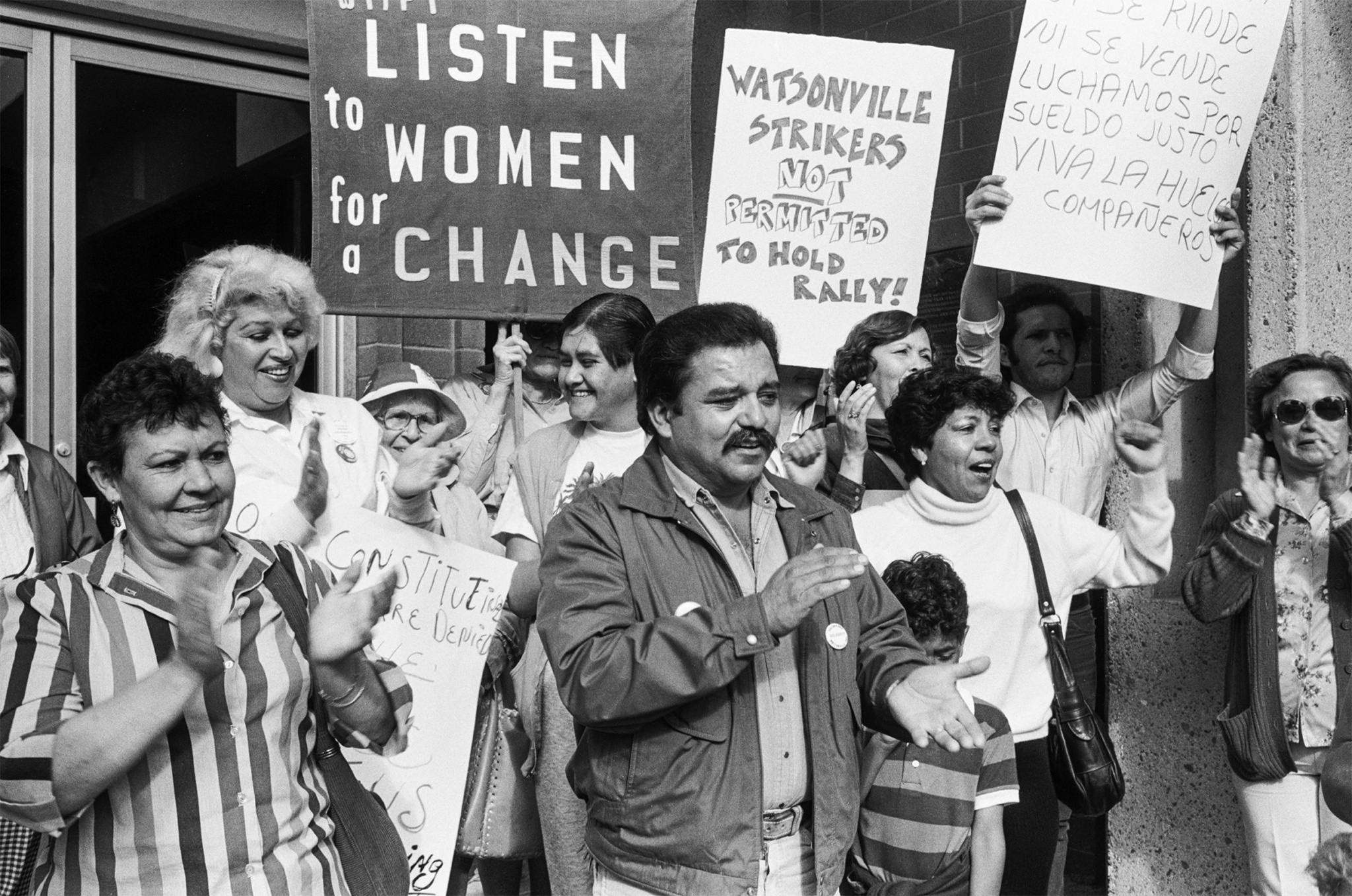

President Ronald Reagan in the 1980s ushered in a frontal attack on labor. It was an era of outright union busting and lost strikes. But the story of the one thousand mainly Mexicana workers of Watsonville Canning, the largest plant in what was then the “frozen food capital of the world,” had a surprisingly different ending.

When I got involved in the Watsonville strike, I was editing the labor section for Unity newspaper, published by the now-defunct socialist organization, the League of Revolutionary Struggle. The League had organized a statewide cannery workers network, and Watsonville’s Teamsters for a Democratic Union chapter affiliated with it. Several League organizers were on the scene and developed close ties with the strikers, so I got on-the-spot reports and went down to Watsonville for the big support rallies.

It was a long shot that low-paid women workers, some of whom were Spanish-speaking only, could win a strike. The media ignored it, uninterested or unconcerned about the fate of Mexican women workers. I was happy to at least be covering it for our newspaper. Their story stayed in the back of my mind, and I knew its lessons were important for the labor movement to hear.

Thirty years later I finally got a chance to write about it in depth. It wasn’t until researching my book Song of the Stubborn One Thousand and interviewing the strikers that I began to truly appreciate what the strikers had to do to win. The hardships they endured, the difficult choices they had to make, the incredible strength they demonstrated — they were just too stubborn to lose.

Peter Shapiro is the author of Song of the Stubborn One Thousand: The Watsonville Canning Strike, 1985-87, published by by Haymarket Books. As a long-time labor activist, Peter was a union officer in the Portland-based National Association of Letter Carriers from 2002-2008 and currently serves as a delegate to the Alameda Labor Council.

What precipitated the Watsonville Canning Strike?

It was an industry problem. By the early 80s, the frozen food industry suffered from overcapacity. Watsonville Canning’s owner decided he could get a leg up on the competition by driving the union out of his plant. He hired a union-busting law firm, got an $18 million line of credit from Wells Fargo Bank and demanded a 40% pay cut from workers. That did it. They struck!

He planned to run the plant with scabs for 12 months and then petition the National Labor Relations Board for a decertification election, because after 12 months, only the scabs would be entitled to vote. Outrageous as it sounds, many employers used that strategy in the 80s.

These workers were overwhelmingly Mexican women. In one village in the state of Jalisco, 80% of the villagers had relatives in Watsonville. For example, Gloria Betancourt, a rank-and-file strike leader, came to Watsonville in her early teens. Her father, a bracero, was able to get citizenship and send for his family. But years of hard labor in the fields had affected his health, so Gloria lied about her age and got hired at Watsonville Canning, the oldest and largest of the local frozen food plants. I asked her how she got away with it. She said, “You just slap a little makeup on your face, it makes you look older.”

The frozen food industry was still new and had expanded rapidly in the 50s and 60s. The pay was better and the work was steadier than farm labor — no traveling around following the harvests. Workers even had union-negotiated health benefits, which was a big deal.

What role did the Teamsters Union play?

A tough old merchant seaman with a fondness for booze ran the Teamsters local in Watsonville. He didn’t speak a word of Spanish and ran the local with what’s called “the padrone system” — “I take care of my people, no need for anyone else to get involved.” The union contract covered all the town’s frozen food plants. He drank with all the plant owners, and, while the industry was expanding, he got pretty good contracts from them. But one owner broke ranks, and the whole thing fell apart. He went off on a binge and then flat-out quit.

The Watsonville Canning workers were mistrustful of the union. As members, they were more or less invisible. Margarita Paramo, one of the strikers, said they were expected to just “pay our dues and be happy.” When the strike began, the union was barely functioning, and the strikers pretty much had to run the strike themselves.

But the Teamsters higher-ups knew that losing this strike would drive them out of the industry, so they were willing to spend money to win. Aside from strike benefits and legal fees, they put $20,000 a month into an economic sanctions campaign against the owner. They hoped to force the owner out of business by negotiating quick settlements with his competitors, even though it meant making concessions that would also apply to the Watsonville strikers.

The Teamsters needed the strikers too. Ten months into the strike, they realized that if the strikers petitioned for a labor board election before the twelve months were up, they could vote along with the scabs and maybe prevent the union from getting decertified. Winning the vote required a close to 100% turnout.

But the strikers had scattered. Some had been evicted and were living in cars or doubling up with other strikers. Some had left town to follow the harvests and earn enough to tide them over. Several dozen went back to Mexico to wait out the strike.

Yet every one of them came back to town for the day of the vote. And the Teamsters won!

That was the strike’s turning point. The strikers made it happen, and the Teamsters knew it.

One thousand workers went out for 18 months, and not one person crossed the picket line. What was responsible for that amazing mass commitment?

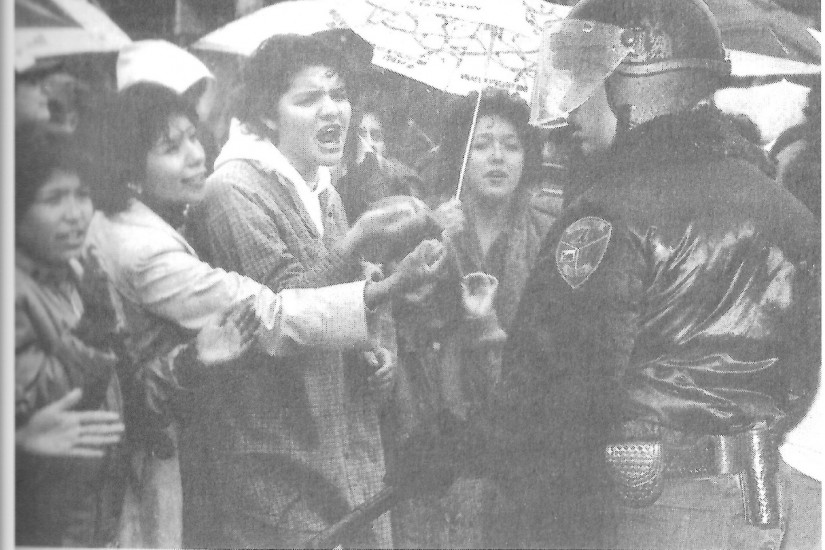

They took care of each other the way you do for family — some were family. The women were uncomfortable in the union hall because the men resented their presence, so they met in each other’s homes to talk strike strategy. The rank-and-file strike committee kept tabs on strikers who left town.

If someone’s kid needed watching, or if someone was pregnant or having trouble with her husband, her fellow strikers were there for her. Everyone knew everyone else’s business. No one thought about scabbing. If they did, they knew they’d have to face their neighbors.

And they were tough. Gloria Betancourt said, “Just because you’re Catholic doesn’t mean you can’t throw rocks at scabs!”

Maybe it helped that the strikers had to organize themselves independently from the union — an enormous responsibility but a shared one, forcing them to rely on each other. Even before the strike, they faced race and gender discrimination on and off the job and confronted it together. They called themselves “stubborn Mexican women.”

How did the strike end?

The owner owed a $5 million debt for broccoli to a local grower who knew that, with the company in foreclosure, he was unlikely to get his money back. He realized the only option for him was to buy the plant, settle with the union, hire back the strikers, operate it at a profit and recoup his losses. Unlike the old owner, he knew he needed experienced workers to make it pay.

Against all odds, these thousand Mexican women workers won!

How did the strike affect the Mexican community in Watsonville?

When the strike broke out, Mexicans were close to a majority in Watsonville but largely invisible. During the strike, the workers went to the City Council to protest police action against them, but the chair refused to allow Spanish translation, saying it would waste the council’s time.

The struggle to be heard started at their workplace, but these women didn’t stop there. After the strike, a successful voting rights lawsuit resulted in district elections, and the workers were able to elect allies to the City Council. City business was conducted in Spanish and English. As for the Teamsters, former strikers were elected to union office, and the local was rejuvenated. The women, their families, their union and Watsonville were forever changed.

-

People’s Mañanera February 9

President Sheinbaum’s daily press conference, with comments on scholarships, return of mining concessions, PRIAN exposed, Bad Bunny Super Bowl, and aid to Cuba.

-

8 Million App Users, TV Soap Opera Ad… & the PAN Still Can’t Find New Members

In Mexico, where political parties are currently publicly financed, the right wing PAN has spent a staggering amount during its lackluster recruitment drive.

-

Mexico’s National Film Archives Workers Demand Dignity

“Our struggle is legitimate; we are not asking for privileges or luxuries, only better working conditions and job security. We also seek dialogue. This situation has become unsustainable.”