Sovereignty is not Decreed, It is Manufactured

This editorial by José Romero, Director of Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas, appeared in the July 14, 2025 edition of La Jornada, Mexico’s premier leftist daily newspaper.

The global economy is undergoing a profound reconfiguration. The United States has taken a protectionist turn, dismantling the logic of regional integration built over decades. In this scenario, Mexico can no longer expect an avalanche of investment as a reward for its geographic proximity and its accommodation with Washington. That certainty no longer exists.

The Mexican government insists that US demands on migration and security have been met, and asks that we not be mistreated. But the USMCA is bankrupt. Trumpist spokespeople—like Steve Bannon and Tucker Carlson—make no secret of their agenda: close borders, expel migrants, repatriate industries, and break ties of dependency. Mexico has no place there, not even as a junior partner.

Trump clarified on July 3: “The tariffs we imposed will not be removed. We will expand them if necessary.” Days later, the White House sent an official letter to the President, announcing another 30 percent tariff, effective August 1. The argument: inaction against fentanyl and the cartels. It warns that any attempt at trade retaliation will be punished with additional measures.

On July 12, Mexico announced the dispatch of a delegation to the United States. Meetings with US agencies and the establishment of a supposed permanent binational forum were reported. The delegation expressed its rejection of Trump’s measures and a willingness to engage in dialogue. This was a symbolic gesture, with no prospect of concrete results or progress. This response not only failed diplomatically; it also revealed the fragility of a model that, for decades, relied on subordinate integration.

As long as Mexico remains weak, the discourse of sovereignty will be domestic rhetoric.

In Mexico’s economic arena, there persists an overly cautious approach, when decisiveness and leadership are required. The government has opted to manage inertia instead of charting its own course. The responses have been more defensive than strategic. The President enjoys broad and legitimate support and has charted a transformative course. This is not enough if those who must translate her vision into economic policy remain trapped in inertia, without direction or strategy.

This crisis reveals a structural change: the bilateral relationship is no longer strategic; it now depends on Mexico meeting US conditions, without reciprocity or real dialogue. The narrative of integration is over. The old dream of lasting cooperation with the US has died. Mexico must stop waiting and start building sovereignty.

But forging a path of its own doesn’t just mean breaking dependence on the US: it also demands reviewing the influence of large foreign corporations operating here. Many are pressuring the government to keep the USMCA rules intact, secure tax privileges, and avoid policies that strengthen domestic suppliers. As long as strategic decisions continue to be conditioned by external interests, talking about sovereignty will be a contradiction in terms.

Nearshoring has worked as a slogan, not a policy. In the first quarter of 2025, Mexico received more than $21 billion in foreign direct investment. But 78 percent was internal reinvestment between subsidiaries, and less than 10 percent was new investment. The supposed boom is not reflected in productive linkages or technology transfer.

The Mexican economy is showing clear signs of stagnation. In May, activity fell 0.3 percent, industry contracted 1.1 percent, and more than 93,000 formal jobs were lost. Industrial production fell 0.8 percent compared to 2024. Although there was a marginal monthly rebound, the trend remains negative.

The manufacturing PMI has been in contraction territory for over a year: 47.4 points in May. There’s no momentum.

Almost a year into the new administration, we still lack an economic growth strategy. As long as the economy doesn’t take off, social programs will be indispensable. Without growth, these programs will be financially unsustainable: social spending will increase without a productive base to support it, and the State will lose its scope for action.

With sustained growth, however, per capita income increases, employment is formalized, and well-being becomes structural. State support strengthens rights. Without a dynamic economy, we run the same risk faced by progressive governments in Latin America: spending without producing, distributing without creating wealth. The outcome: debt, inflation, capital flight, devaluation. And then, the return of the right with its chainsaw. It’s not enough to resist: we must transform. It’s not enough to distribute: we must build.

The world doesn’t respect poor countries. Only strong economies are listened to. As long as Mexico remains weak, the discourse of sovereignty will be domestic rhetoric. It’s fine that for the good of Mexico the poor come first, but for the good of the poor, the country must be strong. A country is not respected for its humility, but for its size, its dynamism, its technology, and its productive capacity. Without this, there is no possible dialogue in the world to come.

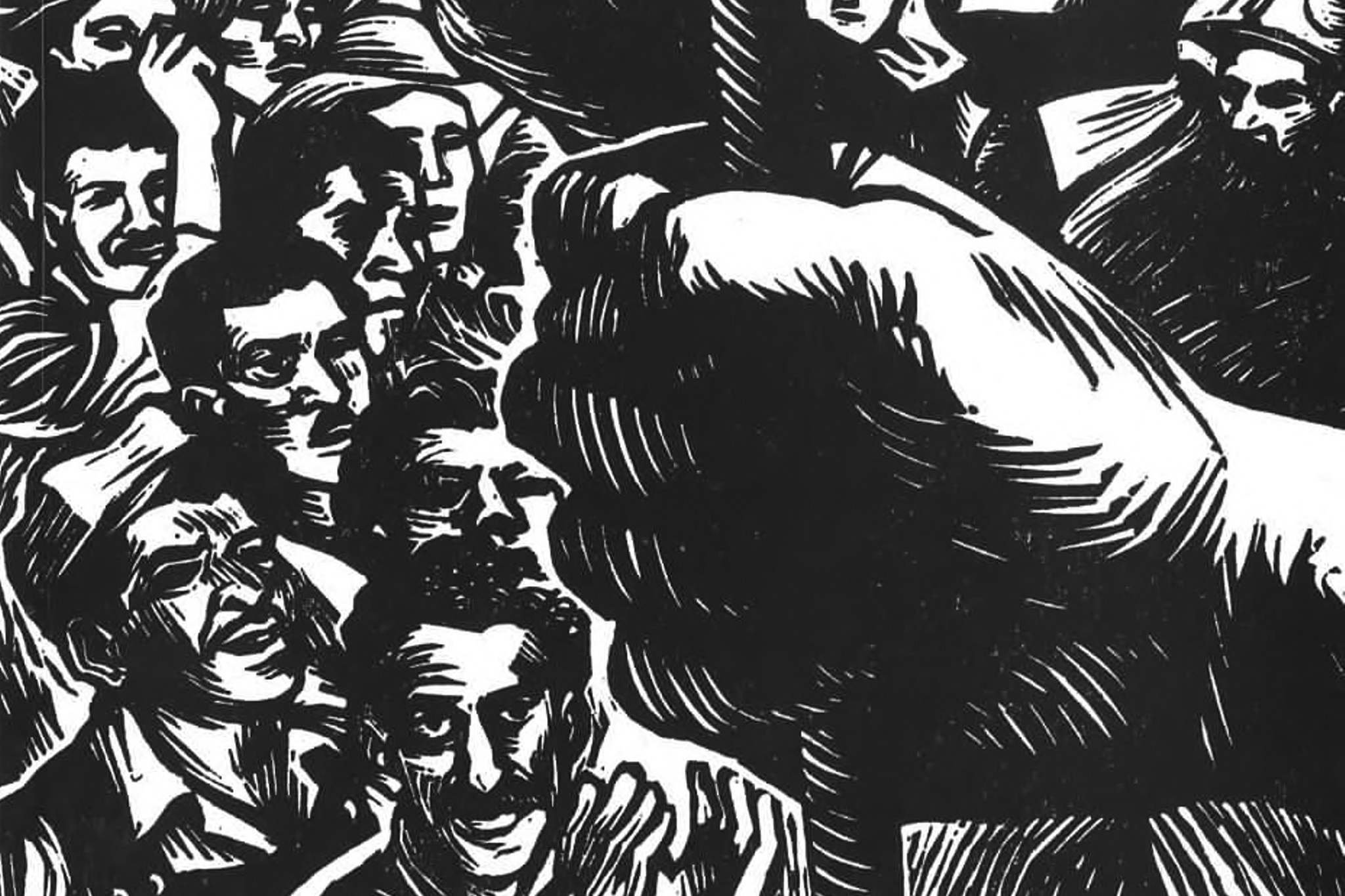

Without a productive apparatus, there is no sovereignty. The Fourth Transformation cannot advance unless it is anchored on a solid foundation, with a modern and autonomous industrialization strategy. Rebuilding the economy does not mean returning to the past, but rather recovering the state’s capacity to drive development. The transformative project must go beyond the symbolic: it must translate into strong institutions, national infrastructure, applied knowledge, and productive chains with domestic added value.

This requires a planning body with real power, constitutional support, and a long-term vision. Not a decorative office or a toothless council, but an operational institution that brings together the business community, public universities, and the science and technology system. A state-level body capable of strategically thinking about the country we want.

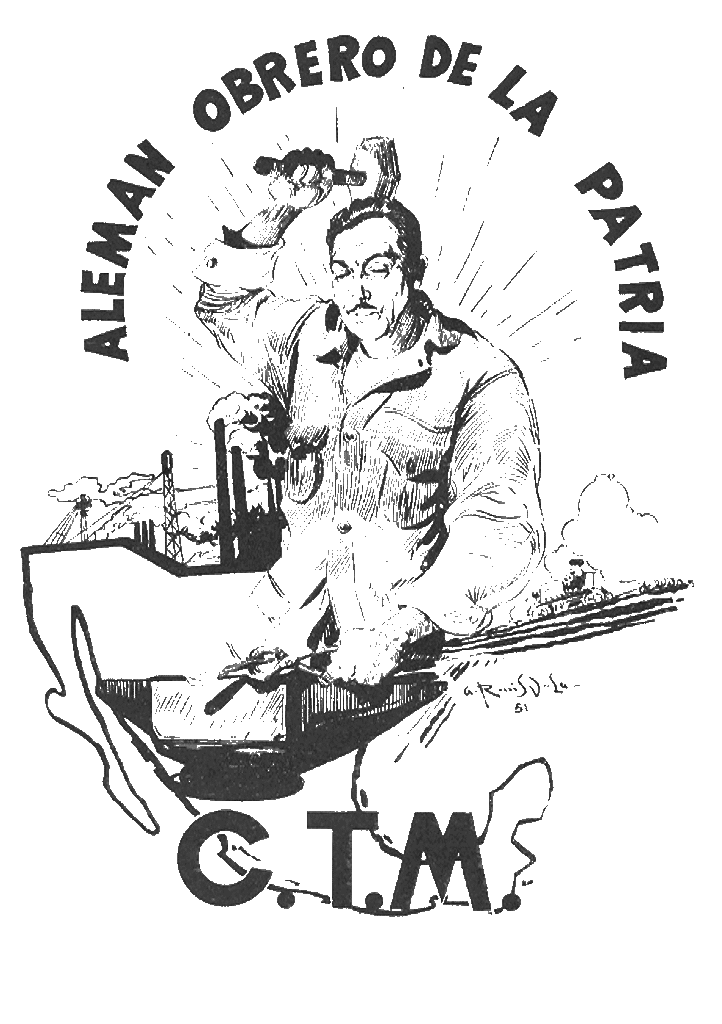

This isn’t technocracy. It’s a survival strategy. Ávila Camacho understood this in the midst of World War II, a very different but equally demanding time in terms of national definition. His government didn’t wait for external guidelines: it promoted a decisive industrialization process. Institutions like the National Finance Corporation—created years earlier—were strengthened, and public investment was expanded to lay the foundations for a modern economy. Key sectors were protected, and infrastructure was strengthened. It wasn’t about managing scarcity, but about building productive capacity. Rebuilding the state isn’t nostalgia: it’s the minimum condition for the country to have a future.

-

Predation & Neo-latifundismo

The government must be very cautious, as the neoliberal regime handed out mining concessions to its predatory cronies like candy, more than half of the national territory ended up in their hands in one way or another.

-

People’s Mañanera February 9

President Sheinbaum’s daily press conference, with comments on scholarships, return of mining concessions, PRIAN exposed, Bad Bunny Super Bowl, and aid to Cuba.

-

8 Million App Users, TV Soap Opera Ad… & the PAN Still Can’t Find New Members

In Mexico, where political parties are currently publicly financed, the right wing PAN has spent a staggering amount during its lackluster recruitment drive.