SPINACH IN THE SPAGHETTI

This interview appeared in the May 27th, 2025 edition of the México Solidarity Bulletin, our weekly newsletter. We encourage you to subscribe!

If kids don’t like vegetables, some parents find ways to disguise them in something the child likes to eat, like spaghetti sauce. For left organizers, a basic question is how to incorporate political education into the spaghetti. Those who are not interested in politics have to ingest the vitamin-filled perspectives that get them off their phones and into the street.

For multimedia artist Einnar Espinosa, his veggies came in the form of DC Comics. Some left fuddy-duddies — we all know them! — might harrumph that Einnar’s uncle should have given his young nephew an author like Eduardo Galeano to read and thrown out the comic books, or that such easy-to-read entertainment dumbs down young minds. But for Einnar, that old Batman comic was his gateway to analyzing the way the world works. It opened his eyes to the injustices of capitalism.

Today, we’re being forced to live within what feels like a terrifying comic book, where reality and fiction are hard to distinguish. Trump is the new Joker, bent on authoritarian world domination, with his trademark red baseball cap replacing the Joker’s purple suit. But he goes one further, by marketing that cap to replicate himself like a 3D printer gone haywire.

No individual superheroes like Batman are going to fly in to take down the Joker and his minions. Remember the cartoon character Popeye the Sailor Man, who would down a whole can of spinach to give him strength to fight the bad guys? It’s people like Popeye-Pinche-Einnar who will be able to fortify people with spinach in the form of illustrations, graphic novels, films and more. Visualize the Joker/Trump taken down by an army of Popeyes!

We need to use every form of resistance we can. Eat your veggies! Read — and write — your comics!

Einnar Dante Espinosa is a writer, filmmaker, illustrator, reading promoter, workshop facilitator, and roommate to two dogs and a kitten. He currently directs “El Pharo: Books, Records & Strips.” He won the FONCA, or Mexican National Fund for Culture and the Arts, award and the National Journalism Award for his 2023 collective investigation “It’s Not Collateral Damage, It’s Our Threatened Future.” His two graphic novels, Stanley and Biombo Negro, will be published in 2026.

Did you start drawing cartoons when you were a kid?

My first drawing — and it was pretty good, if I may say so! — was of a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle; Donatello was my favorite. I was four. And as I kept drawing, people said I had talent. But that became more of a burden than a blessing. It’s difficult to have expectations put on you.

My childhood was very hard. My mom dragged me to Cozumel from Mexico City to “live a family life,” but that certainly wasn’t happening — it was a hard time at my house.

And to top it off, the kids at school born and raised in Cozumel hated folks from Chilangoland. They beat me up and made fun of me, not only for being a Chilango — an insulting name for people from Mexico City — but also because I couldn’t pronounce “R.” But I learned that humor is a defense mechanism against pain. Being funny and entertaining became my shield from the bullies.

What kind of graphics influenced you? Mexican or from the US?

When I was little, I watched cartoons on TV, but I didn’t know about comic books or other graphic material until I was nine. At that time, Cozumel had no libraries or internet. It’s a city geared to English-speaking tourists. I read my first book in English; it was hard to know my Mexican identity then.

By luck, my uncle was a photojournalist for Excelsior, a newspaper in the 1990s. He came back from Mexico City’s first comic book convention with four comic books, including Batman: A Death in the Family. He didn’t read them but gave them to me, because I was into superhero stuff. The Batman story was so amazingly complex — it changed my world!

And not only because of Batman’s comic book form. It also introduced me to politics. In one episode, the bad guy, the Joker, kills Batman’s buddy Robin. Where? In Iran! Batman wants revenge, but then the story revealed that the Joker is the new US ambassador to Iran and a representative at the United Nations, or UN. Then Superman gets involved, representing the US government. It was the first time I’d even heard of the UN!

Superheroes can be right-wing or left-wing. Many fans feel that Batman and the Green Arrow are leftists, and Superman and Green Lantern are conservatives.

So, when did you discover Mexico’s graphic artists, and did they show you a path forward?

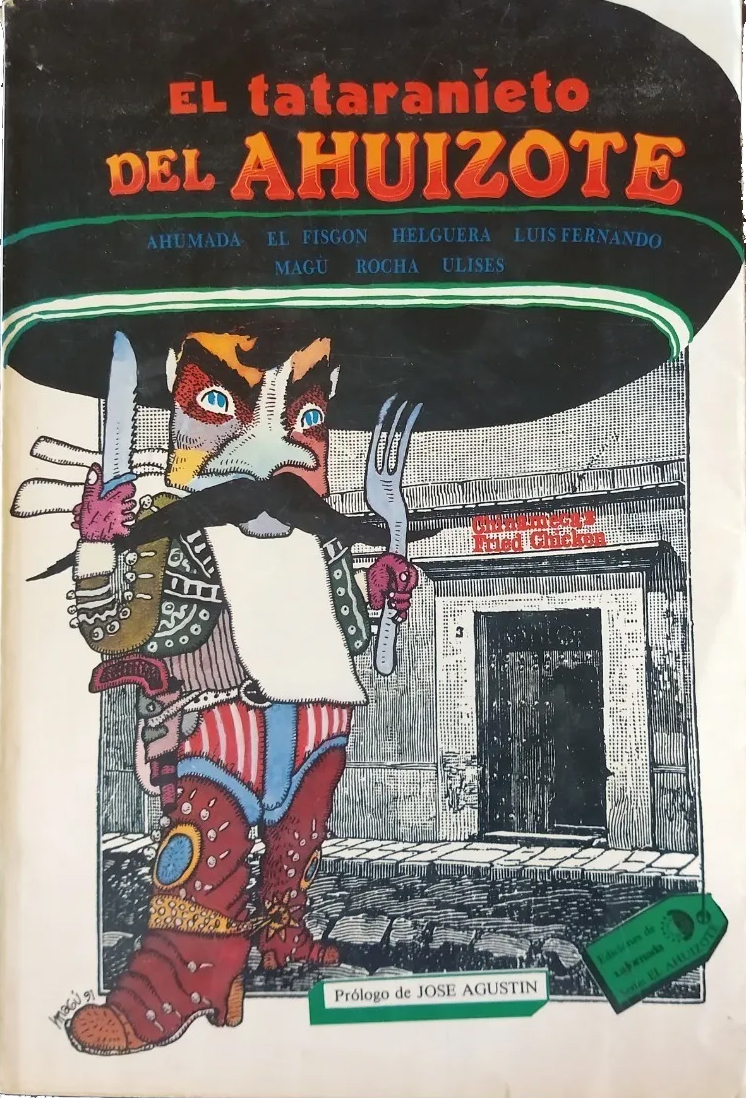

Back in Mexico City, I continued my studies in the 70s and 80s. But before that, my grandpa gave me a great book, El tataranieto del Ahuizote. I became a fan of Magú, pen name for Bulmaro Castellanos Loza, Gonzalo Rocha and Rogelio Naranjo — my trinity, if I must say.

I love these artists, but no, they didn’t influence me. I wanted to be an illustrator, not a cartoonist, and a communicator, not an artist.

I feel you don’t have to be an “artist.” You need a great idea. In fact, when drawing an illustration or cartoon, you have permission to draw badly! What’s important is the spoken words in the “bubble” that help the viewer understand what’s going on. For me, that’s it.

The words come first, the story, and the images illustrate the thoughts.

How did you become a critic of our capitalist world order?

I never read Marx or anything like that when I was young. I didn’t think about the right or the left; I just hated injustice.

In the early 2000s, I had a rock band. I wasn’t political, but then I heard about the desafuera of AMLO. That was when the PRI/PAN wanted to stop AMLO from being eligible to run for President. They cooked up a plan to accuse him of criminal activities, and attempted to strip him of immunity from criminal prosecution. What AMLO said made sense to me, and so I wrote and performed a song called “El Poder” or “The Power.” Audiences loved it; they asked for it whenever we performed. That put me on a political track.

So, my understanding of capitalism started with Batman! In school, you don’t learn anything about how the world works. I learned later that with music, literature, comic books, a great joke — you can get people to look at things in a different light. That happened to me.

Does Mexico have a unique history of making political art?

We owe a lot to José Guadalupe Posada. Without him, we’d have no Taller de Gráfica Popular. The founders used graphics to teach the population about injustice and motivate them to act. People from all over the world came to make political art together in this little workshop in Mexico City.

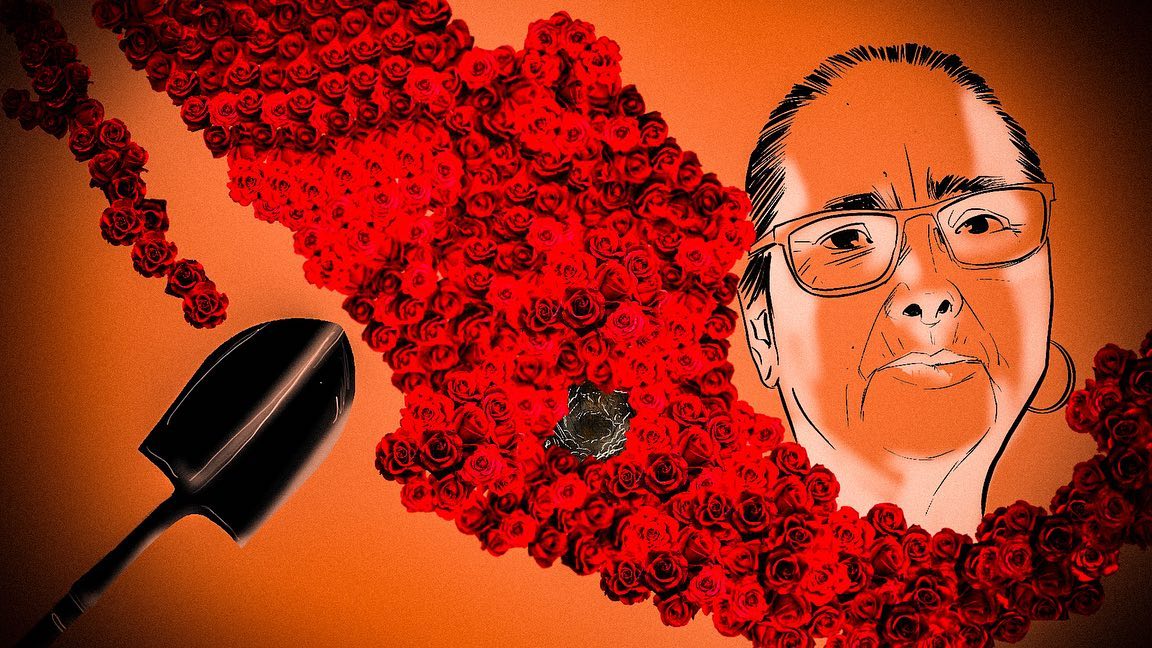

A huge collection of drawings, caricatures, photographs, paintings and more is at the Museo del Estanquillo in Mexico City, which opened in 2006. It was fitting that its first director was El Fisgón!

Speaking of El Fisgón, it says something about Mexico that one of the most important people in Morena — their director of political education — is a cartoonist!

You’ve been a political cartoonist in Guanajuato, one of the most conservative places in Mexico. How has that been?

I moved to Guanajuato when I was 26 to study art, dreaming of being a political cartoonist. I became one, founding and working for the online magazine, POPLab, producing a cartoon every day and illustrating almost every article and investigation. In five years, I made around 3,000 cartoons and illustrations. As a kid, I was called “Pinche,” an inferior, unworthy person. But it’s also used almost endearingly, like “pinche, you funny little devil!” So, I took the pseudonym Pinche Einnar with that double meaning.

Given how corrupt our politicians were, it was easy to satirize them. Journalists are often close to people in the political world, people who tell us the dirt on other politicians. But I came to the hard realization that exposing one politician’s wrongdoing didn’t create positive change. A politician informing me about another one’s corruption was just their way of taking down a rival, and they used me to help them. This realization was depressing, and I decided to stop making political cartoons in Guanajuato.

I just found a music video that I directed and produced. It was released a year after the disappearance of the 43 students of Ayotzinapa (September 26, 2014): 43/Presos Politicos, Libertad — de Botellita de Jerez editado, producido, y dirigado por Pinche Einnar.

Now, I’m having to rethink how to use my drawing. I’m 40, and it’s time to get rid of Pinche Einnar. Cartoonists use graphics to resist injustice. That’s been their role throughout Mexican history. And I will find my place in it.

-

People’s Mañanera February 9

President Sheinbaum’s daily press conference, with comments on scholarships, return of mining concessions, PRIAN exposed, Bad Bunny Super Bowl, and aid to Cuba.

-

8 Million App Users, TV Soap Opera Ad… & the PAN Still Can’t Find New Members

In Mexico, where political parties are currently publicly financed, the right wing PAN has spent a staggering amount during its lackluster recruitment drive.

-

Mexico’s National Film Archives Workers Demand Dignity

“Our struggle is legitimate; we are not asking for privileges or luxuries, only better working conditions and job security. We also seek dialogue. This situation has become unsustainable.”