The CIA & Corrupt Mexican Agents Created the Big Capos Era

This article by Obed Rosas first appeared in the August 27, 2025 edition of Sin Embargo. The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Mexico Solidarity Project.

Mexico City. From Mexico and Honduras to Panama and Peru, the CIA helped establish or consolidate intelligence agencies that became forces of political repression while simultaneously enabling and protecting drug cartels. This has been documented in court reports, journalistic and academic investigations, as well as testimony from former intelligence agents.

In fact, Peter Dale Scott and Jonathan Marshall, in their book Cocaine Politics: Drugs, Armies, and the CIA in Central America, argue that since World War II, one of the most crucial sources of institutional protection for drug trafficking has been the CIA, which, together with the feared Federal Security Directorate, allowed the rise of the Guadalajara Cartel in Mexico in the 1970s.

The first evidence of how the CIA fueled drug trafficking was published in the San Jose Mercury News in August 1996, when it published a series of reports by Gary Webb, who linked the origin of crack cocaine in California to the Contras, the US-backed guerrilla force then led by Ronald Reagan, who attacked the revolutionary Sandinista government of Nicaragua during the 1980s, with the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

“The Dark Alliance,” as the series of reports was called, doesn’t mention him directly, but weaves a web between the Nicaraguan guerrilla opposition, the drug trafficking gangs that sold drugs on the streets of California, and the CIA. The text reveals that the DEA’s own investigations were allegedly abandoned without cause or set aside for unexplained reasons. Webb, the author, committed suicide almost a decade later, in 2004, after the intense pressure he received after revealing the cesspool.

In Mexico, reports indicate how Operation Condor officially consisted of the “eradication of marijuana and poppy crops” through the massive use of herbicides delivered by aircraft in the Golden Triangle of the states of Sinaloa, Durango, and Chihuahua. However, Peter Dale Scott and Jonathan Marshall documented how the plan was used by drug traffickers who, in collusion with security agencies, exploited the operation to eliminate the competition. From there, they maintain, Sinaloa’s main drug traffickers moved to Guadalajara and strengthened their control over the drug trade.

Similarly, there was another key factor: The DFS, then headed by Miguel Nazar Haro, implemented a comprehensive protection process for the leaders of the Guadalajara cartel. In 1985, shortly after the murder of DEA agent Kiki Camarena, a senior US investigator complained that the DFS was “a very serious problem. Every time we arrest someone, they have a DFS card. Many people have been issued plates that aren’t actually on the payroll,” journalist Elaine Shannon recounts in her book, Desperados.

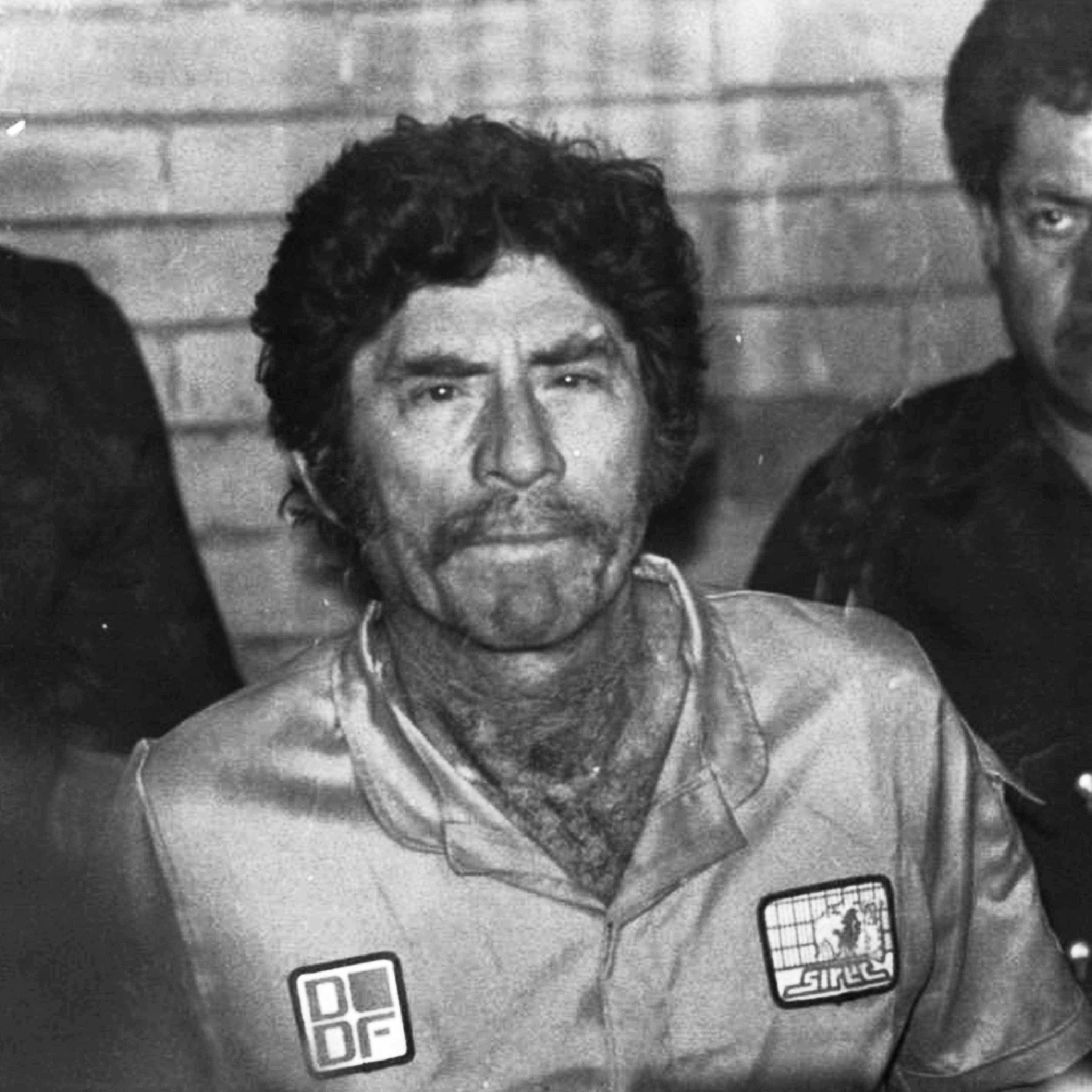

The same report indicates that DFS agents “served as security for traffickers’ truck convoys of marijuana, used the Mexican police radio system to check border crossings for signs of U.S. police surveillance, and transported contraband across the Rio Grande by boat.” Ernesto Fonseca even employed DFS agents as his driver and bodyguard, and in the months following Camarena’s murder, under U.S. pressure, Mexican authorities fired one-fifth of the organization’s 2,200 agents and replaced nineteen of its thirty-one state directors.

The DEA has always blamed drug trafficker Rafael Caro Quintero for Kiki Camarena’s death. Quintero was handed over to the U.S. justice system months ago for this crime and his role in drug trafficking.

Camarena, along with Alfredo Zavala Avelar, an officer and pilot from the now-defunct Ministry of Agriculture and Water Resources, were kidnapped by a group of armed men on February 7, 1985, in Jalisco. A month later, their bodies were found on a ranch in the state of Michoacán, showing signs of torture.

The agent had managed to infiltrate the Guadalajara Cartel and, with his information, allowed authorities to destroy a marijuana plantation valued at millions of dollars. Retaliation was swift.

Both were taken to a farm owned by Rubén Zuno Arce –son of José Guadalupe Zuno, former governor of Jalisco from 1923 to 1926, as well as former brother-in-law of former president Luis Echeverría Álvarez, where they were tortured for several days, until they were murdered.

The DEA reacted with Operation Leyenda, the largest investigation in its history, which identified those responsible: Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo, Ernesto Fonseca Carrillo, and Rafael Caro Quintero. However, in 2013, three former U.S. agents (Phil Jordan; Héctor Berrellez, a former DEA agent; and Tosh Plumlee, a former CIA pilot) revealed their own version of events on Fox News: that Camarena was not killed by Caro Quintero but by a CIA agent.

According to the testimony of the three former federal officials, the DEA discovered that the US was collaborating with Mexican drug traffickers. The case involves Cuban Félix Ismael “El Gato” Rodríguez, who allegedly smuggled Honduran Juan Matta into Mexico: the link between Colombian drug traffickers and the Guadalajara Cartel at the time.

Matta was a CIA operative and trafficked cocaine and marijuana. The money from these illegal operations, which were protected by authorities on both sides of the border, went to the CIA, which used this money, like the crack deal, to finance the Nicaraguan contras. This is what Camarena allegedly discovered at the time, and for which he was tortured and killed, according to the testimony of the three former agents. Authorities later attempted to pin it on the kingpin.

Protected by the DFS & CIA

Peter Dale Scott and Jonathan Marshall point out how the DFS did much more than simply protect the most notorious traffickers. “It united them as a cartel, centralized and streamlined their operations, eliminated their competitors, and, through its connections with the CIA, provided them with the international protection necessary to ensure their success.”

A former DFS consultant revealed the existence of a vast smuggling operation called La Pipa orchestrated by the DFS. According to this informant, in the late 1970s, the DFS acquired around 600 tanker trucks, ostensibly to transport natural gas from the United States for sale in Mexico. On the northern leg of the journey, DFS agents filled the empty trucks with marijuana supplied by Mexican traffickers and transported 10 to 12 trucks a day toward Phoenix and Los Angeles. At the border, several Mexican officials and U.S. customs personnel received bribes of $50,000 per load to allow the trucks to pass, investigators say.

“The relationship between drug traffickers and the Mexican government agency began in the mid-1970s. Two DFS commanders persuaded major drug trafficking families to resolve a bloody dispute over control of drug production in the Sierra Madre Mountains and unite against the anti-drug campaign waged by Mexico and the United States. The DFS helped the families relocate to Guadalajara, introduced them to local officials, and assigned them bodyguards. Meanwhile, the agency, which, among other functions, monitors political subversives and works closely with the CIA, pursued small-time drug traffickers, reducing competition for the new Guadalajara Cartel,” the authors state.

In return, the cartel handed over 25 percent of all its profits to the DFS, Shannon revealed in Desperados. In fact, the Mexican agency also oversaw the $5 billion marijuana plantation in Chihuahua, whose dismantling by federal police in 1984 led to Camarena’s murder.

“This collaboration between the DFS and drug traffickers continued after Nazar Haro left the agency in 1982 with the change in Mexican government; as did the collaboration between the DFS and the CIA. The CIA station in Mexico City maintained close contact with Nazar’s successor, José Antonio Zorrilla Pérez, despite overwhelming evidence of his agency’s involvement in drug trafficking. ‘They don’t give a damn,’ one DEA agent said of the CIA. ‘They turn a blind eye. They consider their job to be much more important than ours,’” Peter Dale Scott and Jonathan Marshall explain.

In Mexico, the murder of journalist Manuel Buendía also occurred at that time in 1984, under the orders of the then head of the now-defunct Federal Security Directorate, José Antonio Zorrilla Pérez, according to Mexican federal courts.

Buendía was the author of the column “Red Privada,” in which he examined the first steps of collusion between the political establishment and drug trafficking in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The central themes were based on exposing the Mexican and international far right and its ties to the CIA. He was one of the first to expose the Agency’s work in Mexico.

For this murder, Zorrilla Pérez was sentenced in 1989 to 35 years in prison, which he did not serve because a judge granted him parole in 2009, 15 years before the end of his sentence.

The Role of the DEA

The DEA itself, at least at the highest levels in Mexico City and Washington, contributed to the cover-up of information obtained by brave field agents in dangerous field offices like Guadalajara, argue Peter Dale Scott and Jonathan Marshall.

“(The DEA) followed embassy orders not to brief congressional missions on the true state of drug trafficking in Mexico in the early 1980s. Even as late as 1984, when the Guadalajara Cartel’s power and reach were evident to field agents, ‘their superiors in Mexico City and Washington seemed oblivious. Cables to the Embassy or DEA headquarters went unanswered, requests for reinforcements were ignored, calls for diplomatic intervention were ignored… The prevailing attitude among many diplomats, and some DEA officials as well, was that corruption and duplicity had to be tolerated to preserve the ‘special relationship’ between the United States and Mexico,’” Shannon noted in Desperados.

It is in this sense that Scott and Marshall point out how Miguel Félix Gallardo, responsible for transporting four tons of cocaine monthly to the United States, was also a great supporter of the Contras, according to his pilot, Werner Lotz, who told the DEA that his boss had advanced him more than $150,000 to deliver to the Contras.

Lawyers for another Mexican trafficker who was tried in the United States stated, according to the authors, that “analysis of all available evidence shows that several federal government agencies, including the CIA, were aware of Felix Gallardo’s cocaine smuggling activities and deliberately ignored them due to his ‘charitable contributions’ to the Contras.”

An Assistant U.S. Attorney did not refute Lotz’s claim, arguing only that it had no bearing on the government’s failure to charge Félix Gallardo with Camarena’s murder. In turn, Scott and Marshall note, a prosecution witness in a subsequent trial for Camarena’s murder stated that Félix Gallardo had boasted about supplying arms to the Contras and rounding up other traffickers to finance his cause during 1983 and 1984, in exchange for protection.

In fact, the Central Intelligence Agency trained Guatemalan death-squads in the early 1980s at a ranch near Veracruz, Mexico, owned by Rafael Caro Quintero, according to a DEA report published by the Los Angeles Times in July 1990.

The report was based on an interview conducted by two Los Angeles-based DEA agents with Laurence Victor Harrison, a figure who ran a sophisticated communications network for major Mexican drug traffickers and their allies in the Mexican police in the early and mid-1980s.

On February 9, according to the report, Harrison told DEA agents Hector Berrellez and Wayne Schmidt that the CIA used Mexico’s DFS “as a cover, in case questions arose about who was running the training operation.” Harrison also said that “representatives of the DFS, which was the front for the training camp, were in fact colluding with major drug lords to ensure a flow of narcotics through Mexico to the United States.”

In another interview, on September 11, 1989, Harrison told the same two DEA agents that CIA operations personnel had stayed at the home of Ernesto Fonseca Carrillo, another of Mexico’s top drug lords and an ally of Caro. The report does not specify when this occurred.

The Los Angeles Times noted that, according to the report, Harrison also told DEA agents in September that, in June or July 1987, an American in Guadalajara—whom he believed to be working for the CIA—asked him what information he had provided to the DEA about CIA operations in Mexico. Harrison claimed to have told the man, “You (the CIA) are working with the drug traffickers… We (the Mexican government and intelligence community) know that the CIA is supplying arms to Nicaragua.” The American, identified in the report only by the name Dale, “nodded his head affirmatively, saying, ‘Yes, I know,’” the report states.

Obed Rosas is the editor of the Research Unit and head of the Books section of SinEmbargo, where he has also served as Desk Manager and Network Editor. He hosts Close UP and co-hosts, with Álvaro Delgado, Siete Días, a program on SinEmbargo, Al Aire. He has worked for other media outlets such as Expansión, Newsweek en Español, and Zócalo Magazine. He holds a degree in Communication and Journalism from the FES Aragón program at the UNAM (National Autonomous University of Mexico) and also studied Hispanic Language and Literature at the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters at the same university.

-

People’s Mañanera February 9

President Sheinbaum’s daily press conference, with comments on scholarships, return of mining concessions, PRIAN exposed, Bad Bunny Super Bowl, and aid to Cuba.

-

8 Million App Users, TV Soap Opera Ad… & the PAN Still Can’t Find New Members

In Mexico, where political parties are currently publicly financed, the right wing PAN has spent a staggering amount during its lackluster recruitment drive.

-

Mexico’s National Film Archives Workers Demand Dignity

“Our struggle is legitimate; we are not asking for privileges or luxuries, only better working conditions and job security. We also seek dialogue. This situation has become unsustainable.”