The Commitment to Human Dignity

This editorial by Tanalís Padilla appeared in the June 12, 2025 edition of La Jornada, Mexico’s premier leftist daily newspaper. On June 5th, Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum defended Cuba’s medical cooperation in Mexico.

1963. Cuba sent its first medical brigade to Algeria. A French colony since 1830, Algeria had barely gained its independence a year earlier, and most of its doctors had left for France. Like a beggar offering help (half of Cuba’s doctors left for Miami after the 1959 revolution), Cuba would send another medical brigade in 1964 to assist in the reconstruction of the Algerian health system.

1965. Twenty thousand U.S. troops invade the Dominican Republic (the second invasion, the first having been in 1916), securing Joaquín Balaguer’s victory over Juan Emilio Bosch, who had previously come to power in the country’s first democratic elections. As president, Bosch committed the sin of implementing agrarian reform, labor protections, and increasing access to healthcare and education—actions that, according to the United States, meant a second Cuba in the hemisphere.

1970. A medical brigade and a construction team arrived in Peru from Cuba to assist the Andean country after an earthquake that left 70,000 dead and 150,000 injured. The Cubans were the first foreigners to arrive in the municipality of Racuay, where they built their first hospital (in addition to five others throughout the country). The supplies the brigade brought included 110,000 blood donations, including Fidel Castro’s. This came despite the fact that Peruvian President Manuel Prado had severed diplomatic relations with the island since 1960.

1970. “Make the economy scream” was one of Richard Nixon’s directives to provoke a coup against Chilean President Salvador Allende. Added to this were: isolating Chile internationally, blocking loans from the World Bank and other international agencies, funding the conservative press, supporting the paramilitary group Patria y Libertad, and CIA plots to eliminate military officers loyal to the constitution.

“We share what we have, not what we have left over,” Cubans frequently comment. Despite suffering the longest and most extensive blockade in history, Cuba continues to contribute disproportionately to just causes.

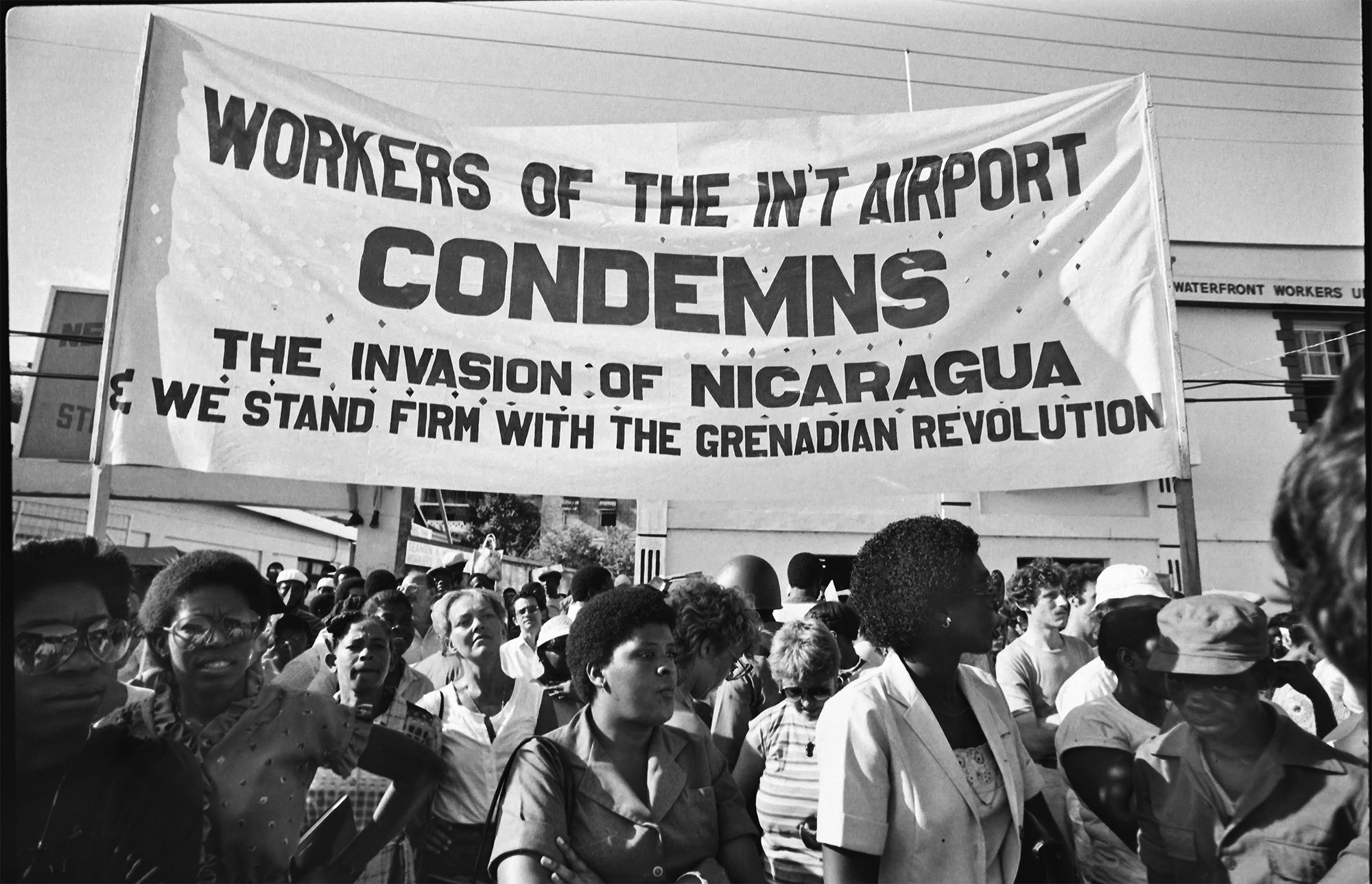

1979-1983. Maurice Bishop governs the small island of Grenada, where, in addition to social reforms, he proposes building an airport closer to the capital to promote a “new, more democratic tourism,” one that would foster exchange and collaboration between peoples. Cuba sent 636 workers and consultants for its construction, a project the World Bank would call the most important factor in the island’s economic growth. Under Bishop, unemployment fell from 49 to 14 percent, access to drinking water increased by 50 percent, and electricity finally reached the entire island.

1981. The Atlácatl Battalion, financed and trained by the United States, massacred the entire population of El Mozote in El Salvador. Under the pretext that the residents sympathized with the guerrillas, soldiers tortured men, raped women and girls, and dismembered babies. With approximately 1,000 dead, it is considered the largest massacre in Latin America. After the massacre and for the rest of the decade, US military support for the Salvadoran government increased, reaching more than a million dollars a day.

1990. The first 139 children from Chernobyl arrive in Cuba. In what has been described as the longest-running humanitarian program in history, between 1990 and 2011, Cuba assisted 26,000 people—22,000 of them children—from the area affected by the 1986 nuclear spill in what is now Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia. The island covered medical, food, housing, and recreational expenses for the children and their companions.

1991. With declarations that Iraq would be “returned to a pre-industrial era” (Secretary of State James Baker), the United States invades Iraq. The war leaves hundreds of thousands of civilians dead. After the military phase, the United States imposes sanctions that, by 1996, had led to the deaths of half a million children. When then-Secretary of State Madeleine Albright was asked if the deaths of so many children were worth it, she replied affirmatively.

2004. Operation Miracle begins. With Cuban doctors and Venezuelan funding, when this program began, patients were sent to Havana for eye surgery. A few years later, 69 ophthalmology centers had been established in 15 countries. The project has restored sight to more than 4 million low-income people in 32 countries in Latin America, the Caribbean, Asia, and Africa.

2015. US President Barack Obama declares that Venezuela represents “an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security and foreign policy of the United States” and imposes a series of sanctions on the country. Two years later, under a policy of “maximum pressure,” Donald Trump increases and extends the sanctions, leading to a collapse in oil production that one analyst would describe as “on a scale seen only when armies bomb oil fields.” According to Alfred de Zayas, an independent expert for the United Nations, the sanctions were responsible for 100,000 deaths in Venezuela.

“We share what we have, not what we have left over,” Cubans frequently comment. Despite suffering the longest and most extensive blockade in history, Cuba continues to contribute disproportionately to just causes. The 600,000 medical professionals who have worked in the world’s most vulnerable areas since 1963 demonstrate their historic commitment to supporting human dignity.

If the Caribbean and Central American countries bow to Washington’s latest pressure to expel Cuban medical brigades, how many more deaths will the empire cause?

In memory of Francisco Javier Villanueva

Tanalís Padilla is a professor and researcher of Latin American history at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Her work focuses on the history of political movements in Mexico, especially the agrarian movements. Her first book, After Zapata: The Jaramillista Movement and the Origins of the Guerrilla in Mexico (1940-1962), already placed her among the leading figures in Mexican political historiography.