‘The Coup’ at Ford: Political Intrigue Across Borders

This interview originally appeared in the April 13, 2022 bulletin of the México Solidarity Project. Please subscribe!

Way back in 1850, the Pinkerton National Detective Agency started up in Chicago as a private police force designed to protect railways from train robbers. But the robber barons that would come into their own after the Civil War needed more than protection from thieves. They needed to protect their absolute authority over their workers. They hired the Pinkertons for that job too. The Pinkertons would soon become notorious for their brutality in stamping out union organizing with fists, clubs, and guns.

Years later, United Auto Workers co-founder Walter Reuther and two other organizers would encounter Pinkertons when they first went to the Ford plant in River Rouge Michigan. The Pinkertons trapped them on a bridge from the parking lot to the plant, then beat them and threw them off the 20-foot bridge, breaking ribs and bones. But this sort of physical violence as an anti-union tool would largely end after the 1935 Wagner Act gave workers the right to organize.

In México, goons and physical violence against workers have never faded off the labor relations scene. During the recent landmark union representation election at GM Silao, modern-day thugs threatened the rank-and-file general secretary of the independent SINTTIA auto workers union at her home.

But in México not just companies bring on the goons against workers. The corrupt CTM union has regularly inserted thugs into Mexican labor relations, and local governments have been just as regularly complicit. And, as we find in this week’s interview with Rob McKenzie, Mexican workers struggling for an independent union voice have historically come up against the vast resources of the US government. The United States has had a heavy hand in stifling worker movements beyond US borders.

A deep interest in labor politics and organizing has led Rob McKenzie to a life-long involvement with auto workers. A 28-year veteran at the Twin City Ford Assembly Plant in St. Paul, Minnesota, McKenzie served as president of his United Auto Workers local and later also won election to UAW’s national bargaining council for U.S. Ford plants. In 2016, after retiring as a UAW staffer, McKenzie began researching a 1990 attack on Ford workers at the company’s plant near México City. That research has resulted in his just-published book, El Golpe: US Labor, the CIA, and the Coup at Ford in México.

Auto jobs started moving from the US to México in the 1980s. In 1990, word of the shooting of nine workers at the Cuautitlán Ford plant reached you in Minnesota.

We were shocked to hear about the attacks on the Mexican Ford workers. We hadn’t had any labor-related bloodshed in US factories since the 1930s.

Just what happened at the Cuautitlán plant?

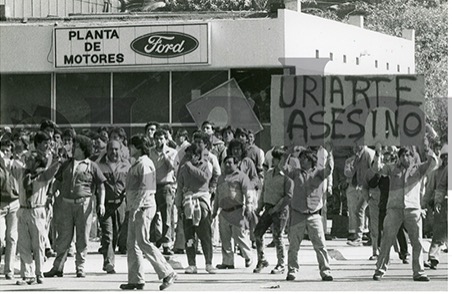

Dissidents in México were challenging the corrupt CTM union at Ford. I learned later that they belonged to the PRT, the Partido Revolucionario de Trabajadores. Their movement had been gaining ground. In 1987, the workers at the Cuautitlán plant had gone on strike because Ford wouldn’t match the 27-percent wage increase authorized by the government. In response, Ford terminated the existing contract and fired everyone. The CTM negotiated a new contract that cut pay by 40 percent and left 600 workers without jobs.

Then, in 1989, Ford fired four members of the local union executive committee who planned to run for national office in the Ford CTM — and probably would have won. After that, right before Christmas, Ford announced it was slashing the yearly bonus. In protest, workers began organizing a work stoppage.

On Monday, January 8, 1990, workers coming into the plant found inside about 300 thugs wearing Ford plant uniforms and badges, posing as “employees.” The workers refused to be intimidated and tried to push the thugs out of the plant. The thugs hadn’t expected any opposition, and they opened fire, wounding nine workers. One later died.

Workers captured a few of the thugs and turned them over to the news media. The initial reports that circulated claimed that a CTM official and a local gangster had hired the thugs.

That story sounds straightforward. What rang false to you about that initial claim?

I could see that getting all those thugs in there had been a massive operation, well above and beyond what it would have taken to resolve a simple labor dispute. This seemed to me like an attempt to wipe out an entire movement not just at Ford, but in all of México.

Another clue that the shooting story had more to it came after my local and others reached out to extend support to the Mexican workers. The US ambassador to México then wrote to the US secretary of state and urged him to get someone to stop us. The ambassador said our solidarity efforts were creating a problem.

In the 1980s, remember, Ronald Reagan was worrying deeply about the Sandinista victory in Nicaragua and the socialists contending for power in El Salvador. Reagan felt the US couldn’t afford to “lose México,” and the strength of the progressive presidential candidate in México’s 1988 election, Cuauhtémoc Cardenas, had taken him aback. Reagan officials, entrenched in a Cold War mentality that saw Latin America as a collection of US client states, undoubtedly supported the stealing of that 1988 election by the pro-US Carlos Salinas. The Iran crisis had just ended, and Reagan was calling México “the Iran next door.”

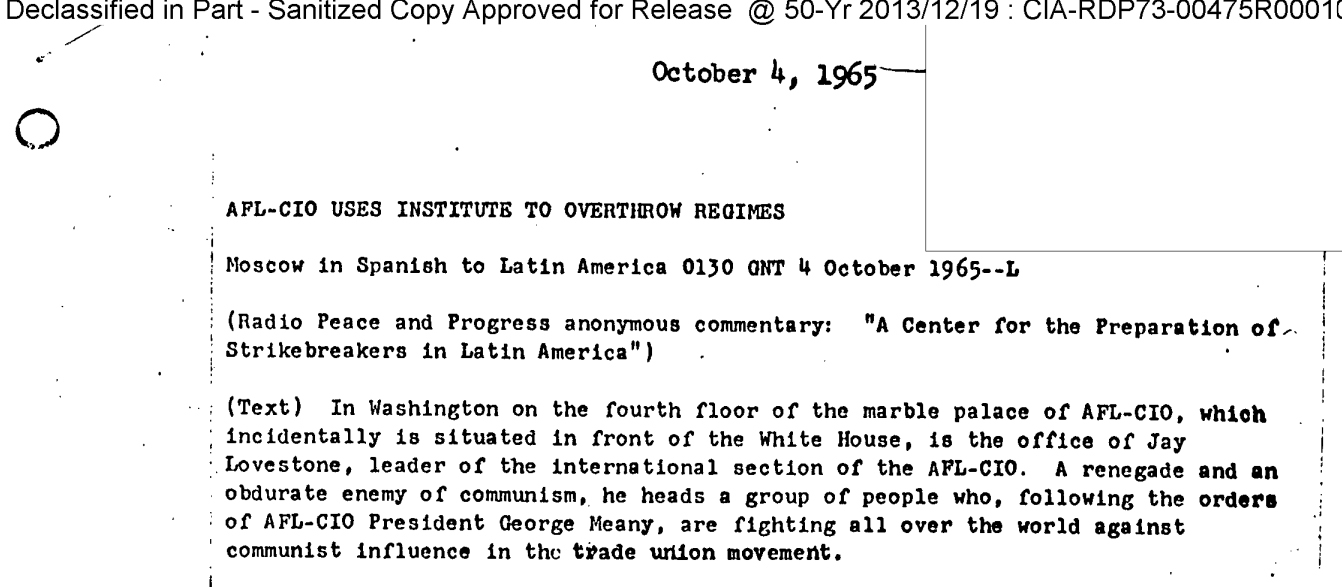

The AFL-CIO at that time also maintained a Cold War mentality, in lockstep with the US government. The AFL-CIO’s American Institute for Free Labor Development, AIFLD, undermined foreign unions and destabilized foreign governments to prevent any left electoral victories. AIFLD, as I note in my book, essentially amounted to a government-created organization managed by the CIA.

Owen Bieber, the UAW president at the time of the incident at Ford, denied any knowledge about the violence. But Bieber had met with CTM officers and served on the AIFLD Board. That leads me to believe that Bieber knew more than he let on. As I kept investigating, the shadowy forces behind the assault at Ford began to take more substantial shape — in the form of the CIA.

You spent years digging up the facts about this case. What drove you?

My family wondered about my “obsession” too! The first time I was asked this question, I didn’t expect it. I got all choked up. I realized that, as a union rep, I had witnessed up close and personal the pain and suffering that laid-off workers and their families went through when the Ford plant where I had worked for so long closed. The attack at the Cuautitlán Ford plant stirred up the same feelings of grief and rage.

What lessons from this sordid and shameful episode should today’s US labor movement be taking?

Back in the 1980s when Ford went to México, few UAW locals got involved in solidarity work. We missed an opportunity. Today, more than ever, the US labor movement needs to make international solidarity a core value.

And our labor movement must also confront its past. You can’t make a course correction unless you explore what you did wrong, with an open mind and an open heart. US labor was on the wrong side of history. And that’s the truth.