THE LAW IS NOT THE SAME AS JUSTICE

This interview with Federico Anaya Gallardo by Oscar David Rojas Silva, Carolina Hernández Calvario, Mylai Burgos Matamoros, and Luis Lorenzo Córdova Arellano appeared in the May edition of Memoria: The Magazine of Militant Criticism.

Editor’s note: Federico Anaya Gallardo is a candidate for Minister of the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation in Mexico’s judicial elections, which take place on June 1st, 2025. Anaya Gallardo was a proponent of last year’s constitutional reform, and has a long career in public service and politics, as the legal director of Mexico City’s Ministry of Culture, with the San Luis Potosí Human Rights Commission Council, and as a trainer at Morena’s National Institute for Political Training (INFP). He holds a law degree from UNAM and a doctorate in political science from Georgetown University. We hope this interview elucidates some of the social and political dynamics in the forthcoming judicial elections.

Who is Federico Anaya Gallardo?

I introduce myself with some embarrassment. I’m a lawyer, and I confess that after finishing my law degree at the UNAM School of Law, I tried to escape law. I went on to study for a PhD in Political Science, trying to escape legal formalism and the most arid interpretations of the law. I might have preferred, if I’d been told in high school that I could be an anthropologist, but they didn’t tell me that anthropology existed, or I was very ignorant about these subjects. So I studied law.

I escaped being a political scientist, but in 1994, a rebellion broke out in Chiapas, as you all know, and the Fray Bartolomé Human Rights Center in San Cristóbal de las Casas didn’t have lawyers because organized civil society didn’t trust lawyers, because they were formalistic, because they were in the conservative social camp, because they didn’t serve the people. For the rebellion and for what came after, they needed legal services, committed lawyers. I remember telling the colleague who contacted me that they were looking for the impossible; socially committed lawyers don’t exist.

I needed a thesis topic for my doctoral research in Political Science, and I returned to Chiapas, and there I discovered the grassroots utility of law. So, it was a kind of reconciliation: who am I? A lawyer who tried to escape law, and then material reality, social organization, brought me back to legal practice.

How do you understand Judicial Reform?

Here’s something strange, if you want to look at it in formalistic terms. Because we’re a democratic, liberal republic since 1857, in theory, all public powers emanate, as the Constitution states, from the people. This means that the powers must be elected by the people, by the people. At the origin of the Mexican nation-state and its liberal organization in 1857, the Court was also elected, so our Constitution was very consistent in this regard.

During the Porfiriato, they began to have second thoughts, as the Americans say, and said, “No, maybe it’s not so good that the Court be elected.” So in 1917, we changed the direct election of the judiciary, and since then, until the present, 2025, nearly 110 years have passed, more than a century, without having elected anyone to the judiciary.

We thought the judicial reform proposal would only involve the popularly elected Court, as it was originally, but it turned out to involve the entire judiciary; it’s much more radical. This is similar to what I told you happened to me many years ago. I was happy becoming a political scientist, and suddenly, a popular movement forced me to reconnect with the law.

We’re told that electing judges won’t work because law is supposed to be a very complex, obscure science that only those initiated and highly trained in universities can understand. The popular response to this is that law is not the same as justice, and what we want in the courts are people who deliver justice.

Here, there is a popular movement, which is Obradorism, a historical reality, which first manages to conquer executive power, then legislative power, and, through a very strange debate that is what led to Plan “C” and judicial reform, there is a political movement opening the judiciary to democracy.

What’s next? It’s not enough to simply elect judges. The options for choosing judges aren’t optimal. Right now, everyone, including our colleagues in the community, must be looking at an immense number of candidate profiles and asking themselves, who’s good for the Supreme Court, for magistrate positions, for the district courts?

The problem, after 110 years of not democratically discussing the election of the judiciary, is what is good and what is bad for a court? These are issues we have yet to begin to seriously discuss.

What’s the relevance of this democratic process?

We’re told that electing judges won’t work because law is supposed to be a very complex, obscure science that only those initiated and highly trained in universities can understand. The popular response to this is that law is not the same as justice, and what we want in the courts are people who deliver justice.

So, there you have a problem: are there or aren’t there experiences with popular judicial elections? Yes, they do exist, and here the most conservative Hispanicists in Mexican society might criticize me, but I’m happy with that criticism: the original model for electing judges is the United States of America, as it’s a society that, in this respect, is built from the bottom up, where judges don’t need university degrees in law, and some, like those on the Supreme Court, only some legal training.

I mean, think of the United States border, and if you want to naturalize it for Mexico, imagine the Lacandon border, while the Tzeltal and Tzotzil colonized the jungle, building political communities and also legal systems. And, although we’re not used to saying it, the Lacandon colonizers also trained judges and a system of lawyers who argued problems. That’s why in Chiapas one of the natural demands was the recognition of normative systems. Today, we white Creole New Spanish speakers continue to defend the academic certificates, but at this time, disguised as Kelsenianism, positivism, even analytical philosophy of law, where law becomes mathematical, algebraic formulas, and so, that’s what it means to be prepared.

Brenda Berenice Morales Garcia, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Based on the above, I would propose an even more radical judicial reform: Why don’t we have lay judges? Judges elected by the people, not because they are better or worse lawyers, but because they have the criteria to solve problems.

We’ve always said, if a lawyer must fight for the law, but suddenly comes across a legal norm that is unjust, then he or she must fight, not for the law, but for justice, right? What if the problem isn’t just in the law, but in reality? You can have a set of rules in the books, but reality will always present new problems.

To illustrate, I’ll jump to a specific case that Mexican society has just experienced. We all agree that we must protect the most vulnerable, and the most vulnerable human beings are newborns. We have an 18-year-old teenager who procreates with a 22-year-old partner, and they don’t know what to do with their child; in fact, they weren’t even sure what month of pregnancy they were in. So, they think they’re terminating a pregnancy, and what happens is the child is being born, and they abandon it. That’s attempted murder, according to the book.

But if you look at the situation, where’s the injustice? In that these people threatened the life of the newborn, or in that she, who’s working, can’t work, and won’t find a job. Or, she just got a job at a bakery a month ago, but if they find out she’s pregnant, they’ll fire her, and then she’ll have no income. It’s even possible that the young couple will be kicked out of the uncle’s house where they’re staying, with no income, no place to live, anyway. Where’s the injustice?

Well, on both sides, we obviously have to protect the life of the newborn, but shouldn’t we also have protected the development of those two young people? So, they’re being criminally prosecuted, but if we go back to the books, they’re probably going to get a conviction for attempted murder, because the good news is the newborn survived.

Let’s compare the two cases. For attempted murder, the young men could be punished, just like another Mexican, Fofo Márquez, who warned us for five years that he was an aggressive, racist person who abused the economic power his family had accumulated over two generations. One day, he lost control and almost killed a woman. He was charged with attempted femicide and sentenced to 17 years in prison for the attempted murder.

The problem is that, if you look only at the books and the law, perhaps, in one of the combinations, the young people in the first case I mentioned will be sentenced in the same way and with the same sanction as in the second case. Do you think that’s fair? At the very least, it should give us pause for reflection.

What of the right to social justice?

The paradigm we’ve had until now, for the last 30 years, is that you have to prepare legal experts and experts in conflict analysis. Their training takes place within a judicial school, you administer internal exams that are never public, and you select the best.

What’s the problem? People don’t understand the criteria used to train these officials.

Furthermore, we have been discovering that the results of this administration of justice are not optimal; they do not benefit us. We have discovered with horror that 90% of the Supreme Court’s important rulings are on economic and tax matters. That is, only large businesses that want to avoid paying large amounts of taxes can afford lawyers with that level of specialization in legal language who can debate whether their right to equal taxation is being violated.

In contrast, there are very few Supreme Court rulings on social rights, almost none on health, and very few on environmental matters. And when an indigenous community, for example, manages to bring an issue to the Supreme Court through an amparo (proclamation) after 12 or 15 years of litigation, the Supreme Court simply resolves the case and fails to establish strong precedents and jurisprudence on these issues—that is, ones that apply to all communities and are substantial in the defense of their rights.

So people say, “This judiciary isn’t delivering for us. They’re very well-prepared. We understand that law is a very complicated thing, and they’re the experts, but their results are minuscule in terms of social need.”

The first solution is, we want to open up the system, instead of having a judicial school as the sole criterion, what we want is to introduce popular vote, that’s fine.

What’s the problem? The popular vote can’t be limited to the initial election. The reform states that almost all judges, after nine years, must undergo another election if they wish to continue in their work as judges. Currently, our Supreme Court is elected for 12 years and there is no reelection. There’s a problem here: we would need the popular democratic impulse to intervene again and say, I don’t know, every three years, how has the minister behaved? And we submit the mandate of these judicial officials for revocation or ratification. This is lacking in the process we are currently undergoing.

But there are other things missing. How do you ensure that popular justice criteria are introduced into the judicial system?

First, we would need people who aren’t necessarily lawyers. If you look at how things are today, everyone is a lawyer, some less formalistic than others. I myself could say that I’m also infected with the formalist virus. Why? Because I was trained in traditional schools. So, the first thing would be the lay judges I already mentioned.

Second, not just in criminal matters, but now that I’m thinking about it, in some matters like honor, freedom of the press, and the right of reply, wouldn’t it be more favorable to have juries? I mean, who better to judge whether someone’s honor has been offended than the community surrounding that person?

Mexican law once included juries, and the reasons for removing them, if you review the arguments, are always elite. They tell us again: “The jury isn’t a legal expert.” No, it’s not about them being legal experts; it’s about them being ordinary people, who apply general criteria of justice. And there may be a legal expert, a judge, who in that case must be a non-laity.

Let’s say, a slightly crazy combination would be to have a jury and a lay judge. Then there’s no one who can say, “Hey, the law books say such and such, so there needs to be some rule.” What’s the problem? The laws, the more modern French would say, are there, and the judge simply refers to them when he has a case to resolve. I prefer the Anglo-Saxon style: reality, which may contain many new injustices, has to be analyzed. The judge has to explain to the people what the problem is, and then, together, reach a conclusion. If you don’t have a jury, the process should be transparent.

I’d like to conclude that point with something we already did in Mexico. No one knows exactly why, and if you look at it, for example, Ana Laura Magaloni once criticized the fact that our Supreme Court holds its debates in public and on live television. She comments that this is terrible because it exerts undue public pressure on the justices.

No, I think that’s a step in the right direction, because imagine, we’ve already elected them, now we’re going to see how they behave, and then it’s going to be very important to see what arguments they’re arguing with.

However, some things need to change. If you open any of the Supreme Court debate pages right now, you’ll probably fall asleep.

Why? Because the way they organized the debate that is filmed is tremendously complicated, they discuss resolutions and sentences in parts.

But what should we do? Much more fluid debates, where reality is discussed and not just the legal framework, and that, paradoxically, will educate people.

With that we end up, surely, in another paradigm of law.

Law is not something created by specialists and then taught to the people. Law, as my professor Gutiérrez y González said, is common sense systematized through practice, and practice has to be communal.

Are judges political actors or guarantors of legality?

I’ll start with the big book that is the Constitution. The Constitution states in classic 19th-century Mexican language that there are three supreme powers of the Union: the executive, the legislative, and the judicial. I mentioned them separately in Hispanic order, with the executive first. If we were Anglo-Saxons, we would say the legislative first. We always put the judicial last; it’s the third power, and it’s a strange thing because we forget it’s a political power. So, if you go all the way to the head of the judicial branch, the Supreme Court, of course it’s political.

The major issues the Court would have to decide, for example, are when a governor of one of the federal states has to appear before a criminal judge to explain why he bought an apartment for 300 million pesos, even though he never earned a salary that could justify the purchase. This was the case of Francisco García Cabeza de Vaca. There were also many other accusations against him, and if there hadn’t been a cloak of political impunity hanging over him as governor, the judiciary would have also had those cases to debate and resolve.

But what happened? Well, it’s proven that the Supreme Court is a political power, of course it is. The Court made the decision in this matter not to rule; it came up with a dispute over the governor’s immunity. The federal legislative branch stripped him of his immunity, and then the Attorney General’s Office tried to bring the case before a judge, but the accused filed a constitutional dispute, saying, “No, this judge doesn’t have the power to decide; let the Supreme Court resolve it.” And the Court decided not to resolve anything. It took a year and a half, and when the trial finally ended, it turned out that he was two or three days away from being no longer governor. This case is a breach of the Court’s political responsibilities. It doesn’t take a year and a half to resolve a legal issue that is also political, only for the conflict to be resolved almost naturally because the accused’s term in office has ended.

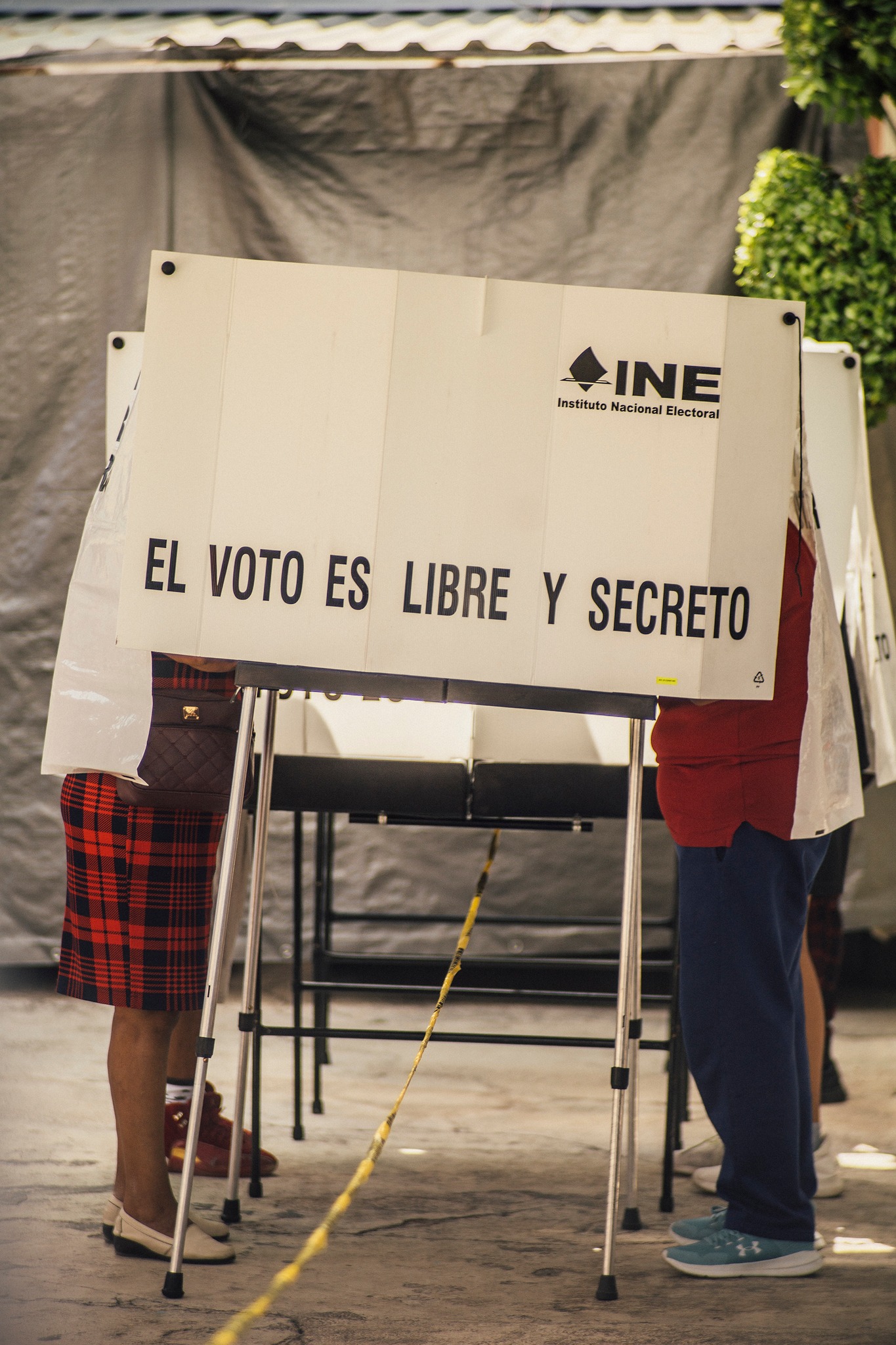

What does it mean to participate and where are we going with this judicial election process?

It seems to me that voters have an incredibly difficult task ahead of them. This is an election where there are no parties, meaning it won’t be easy to identify which party or which party to vote for.

Therefore, during those two months, they will have to review what we are saying and proposing.

When we look at specific cases, everyone wonders what a fair or reasonable resolution would be in this case. Right now, we’re choosing who will make those decisions. Centuries, many centuries ago, in one of these old medieval codifications, it said something like: it’s not that we need good laws, we need to have men as judges—we would now say, and women—fair, equitable, capable of making decisions. That’s what people have to do, and it’s difficult work.

For this reason, what we as candidates need to do is express our perspective on where we come from, how we think about legal issues, how we’ve resolved them when we’ve been judges, how we could resolve them, or what we think is the best resolution in current and future cases. This is the only way for the people who are going to vote to form a criterion for the election.

They say this is impossible because people lack the capacity to understand such complexity. No, systematized common sense, that’s what law is. People will gradually discover that it’s not that difficult, and that behind all the bombastic words of legal jargon used by lawyers, there are things that are more or less simple to understand, and with these criteria, every time we have a judicial election, things will go better.

-

Attack on Venezuela: Mexico’s Response

An interview with Daniela González López of Observatorio de Derechos Humanos de Los Pueblos.

-

A Migrant by Any Other Name is a Migrant

Diego Alfredo Torres Rosete lived in the US as an undocumented immigrant for 20 years. Now back in Mexico City, he’s a founder of Frente Amplio de Mexicanos en el Exterior.

-

“Clueless” Morena Governments Signed Privatization Agreement: Marx Arriaga

“Just because the government or its leaders are from Morena doesn’t mean that all institutions have a progressive vision,” the Director General of Educational Materials commented.