The Return of Large Scale Mining in Mexico

This article by Zósimo Camacho Ibarra originally appeared in the November 27, 2025 edition of Luces del Siglo.

Editor’s note: we previously published a story in June of this year about the rapacious Canadian mining company Equinox Gold and its devastating impacts on the Mexican people and land.

While the federal Ministry of Economy embraces the mining industry in Acapulco, a community in Guerrero experiences the bitterest side of extractivism: criminalization, scorched earth, and dispossession.

Just days before the Secretary of Economy, Marcelo Ebrard Casaubón, praised the mining industry at the inauguration of the XXXVI International Mining Convention in Acapulco, the ejido of Carrizalillo issued a heartbreaking bulletin: “Faced with the impossibility of submitting us, Equinox is betting on criminalizing our struggle.”

This temporal coincidence reveals the profound schizophrenia that Mexico experiences with respect to its development model: freedom for capital to reproduce itself… but –of course– “with shared prosperity”.

While Ebrard spoke of “accelerating permits” and “facilitating investment” to guarantee “supply chain security,” the ejido members of Carrizalillo denounced that the Canadian company Equinox Gold—after eight months of conflict—has escalated its strategy from environmental negligence to outright criminalization. Not content with having destroyed nearly 1,000 hectares, poisoned springs, and caused serious health problems for families in the region, the company now seeks to portray the land defenders as criminals.

The contrast could not be more striking. In the convention hall, Ebrard was celebrating that “we have already obtained, I believe, the first three” permits and announcing the resumption of larger-scale exploration. Two hundred kilometers away, in Carrizalillo, the open-pit mine operated by Equinox Gold is closed by the Federal Attorney for Environmental Protection (Profepa) due to pollution, and the company continues to illegally occupy the land it refuses to rehabilitate.

The official discourse speaks of “sustainability and environmental labour responsibility”, but the reality in Carrizalillo shows the true face of extractivism.

First, the farce of corporate social responsibility. While Equinox was preparing to “show off the highest international standards” at the Acapulco mining convention, its local operators were intensifying a disinformation campaign to link the ejido members to organized crime.

Second, Canadian cynicism. The same Canadian government that issued travel alerts to Guerrero for its citizens, for real or alleged reasons of insecurity, maintains “deathly silence about the violence that Canadian mining companies carry out in our state,” as the ejido denounces.

And third, institutional complicity. The Ministry of Economy—host of the mining convention—continues to fail to revoke Equinox Gold’s concession despite its indefinite, unilateral, and illegal suspension of the mine, its violation of environmental regulations, and its disregard for the farming families. Why the long delay in enforcing the law?

The Carrizalillo case exposes the lies of mining “development”: after 25 years of gold extraction, the community is left with unusable land, poisoned water, and broken health. The promised prosperity has resulted in miscarriages, skin and lung diseases, and a proposed compensation package equivalent to less than two monthly food baskets per family.

The crucial question that Ebrard avoided in his speech is: what kind of “supply chain security” is built on the legal and environmental insecurity of communities? What “national well-being” is achieved by destroying the well-being of Indigenous peoples?

Carrizalillo’s message to the government is clear: “This isn’t our stubbornness; it’s what the law says.” The farming families are demanding what the legal framework stipulates: if the mining company doesn’t want to operate, it must negotiate a formal closure and rehabilitate the destroyed lands.

Mexico faces a historic crossroads: it can continue down the easy path of pretense – where sustainability commitments are signed in luxury hotels while ignoring real devastation – or it can begin to align its development rhetoric with effective compliance with the law.

The struggle in Carrizalillo is not just about a thousand hectares of devastated land; it’s about the soul of a country that claims to want to transform itself while allowing foreign companies to treat its people with contempt. The true test for the “Fourth Transformation” is not in the carpeted halls of Acapulco, but in the poisoned fields of Guerrero.

Was a six-year term enough to remove the extractive industry from the list of the rapacious oligarchy that is bleeding Mexico dry? Is it always “For the good of all; yes, but capital accumulation first”?

-

Workers Party Claims Sheinbaum Electoral Reform Will Eliminate Party System

The socialist party’s leader recalled the democratic spaces that the left managed to conquer with the 1977 & 1996 reforms, a “fruit of countless struggles, repressions, imprisonments, disappearances and even armed uprisings.”

-

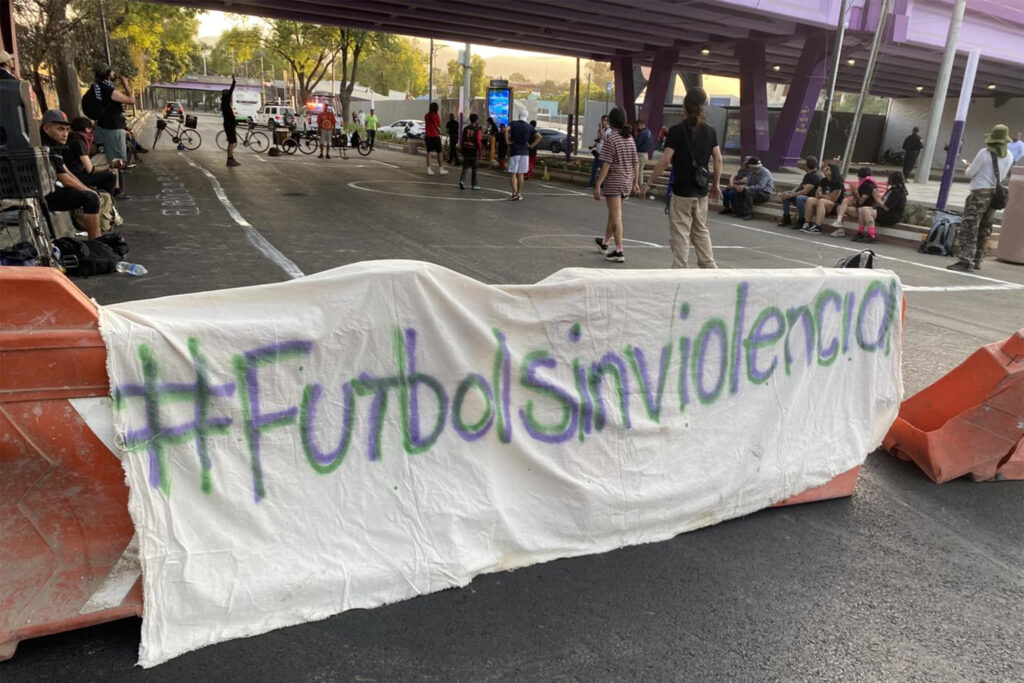

Anti-FIFA Challenge: Football Defends the Territory

Mexico City residents are organizing Anti-World Cup Days to protest water theft and gentrification that have accompanied preparations for the World Cup, put on by the corrupt, international criminal consortium known as FIFA.

-

Tridonex Strike in Matamoros to Start March 6th

1,300 workers are expected to strike, demanding the company fulfill its obligation to pay workers in full. Tridonex is owned by First Brands, the US autoparts corporation accused of massive fraud.