When Mexico Ceased Being an Exception

This editorial by José Romero originally appeared in the February 3, 2026 edition of La Jornada, Mexico’s premier left wing daily newspaper. The views expressed in this article are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect those of Mexico Solidarity Media or the Mexico Solidarity Project.

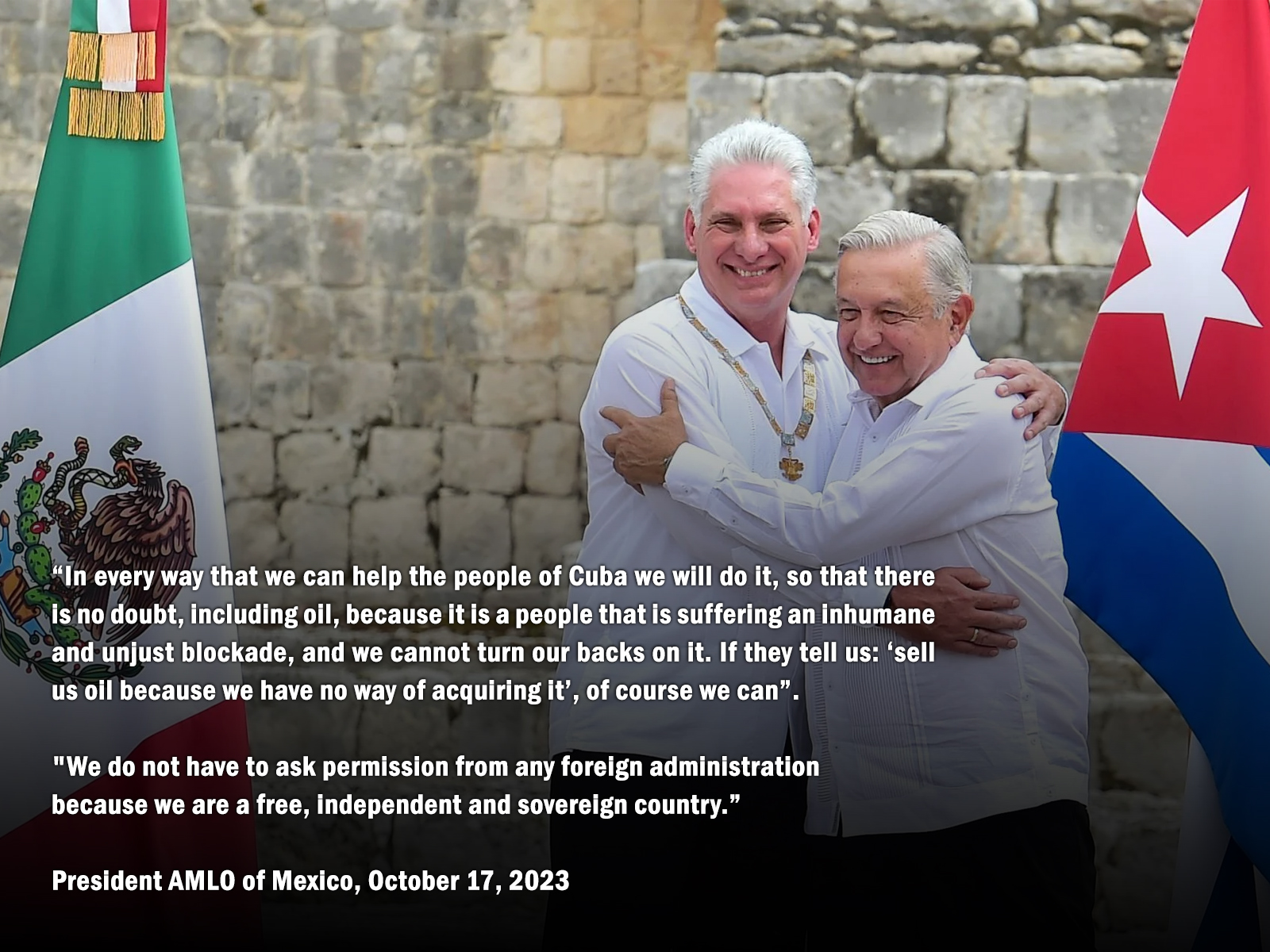

For decades, Mexico maintained a foreign policy that, with all its nuances and contradictions, retained a singular characteristic: the defense of sovereignty as an operational principle, not as a rhetorical slogan. This tradition survived regime changes, ideological shifts, and external pressures of all kinds. Even during periods of closest ties with the United States, Mexico maintained a clear line: non-participation in the political and economic encirclement of Cuba.

That historical continuity has been broken. The immediate context of this shift is well-known. Washington has made it clear that it will impose tariffs and indirect sanctions on countries that continue exporting oil to the island. Faced with this scenario, Mexico has chosen to withdraw from the energy supply and present the decision as a reconfiguration of its support: less oil, more “other types of aid.” The logic is transparent. The aim is to avoid trade penalties by shifting solidarity to a less contentious arena from the perspective of the bilateral relationship.

However, this shift is not neutral. Swapping oil for humanitarian aid does not equate to upholding a policy of autonomy, but rather to adapting to externally defined boundaries. Assistance can alleviate specific shortages and address immediate emergencies, but it does not replace the political significance of maintaining an energy relationship within a context of explicit encirclement. The implicit message is clear: Mexico accepts the US’ imposed limits and is reorganizing its foreign policy within them.

By yielding under [American] pressure, the Mexican state sends a disturbing message: sovereignty ceases to be a guiding principle and becomes a negotiable variable. The idea takes hold that, under certain external conditions, autonomy can be pragmatically suspended without significant public deliberation. This precedent is more serious than any short-term calculations regarding bilateral relations or momentary balances.

The decision cannot be interpreted as a technical adjustment or an isolated administrative measure. It is, in fact, a shift in foreign policy. Not because Mexico has the material capacity to determine the island’s fate—it does not—but because it is abandoning a historical position that granted it a distinct, recognizable, and respected place on the Latin American diplomatic map.

It is important to be precise. Cuba is not currently facing a crisis due to Mexico’s actions. The causes of its fragility are structural, accumulated, and deep-rooted: decades of blockade, the exhaustion of its production model, unresolved internal tensions, and an increasingly adverse international context. To think that the fall or transformation of a government can be explained by a single external decision would be a serious analytical error and a historical oversimplification.

But in international politics, symbols matter as much as material flows. Mexico was not a decisive energy supplier for Cuba. Its weight did not lie in volumes or contracts. It was something different: a political anchor, a persistent reminder that not all of Latin America readily accepted the logic of isolation and punishment. By withdrawing from that position, Mexico does not “bring down” Cuba, but it legitimizes the blockade and contributes to normalizing a policy it has historically questioned from the outset: non-intervention.

The main cost of this decision, however, lies not in Havana, but in Mexico City. By yielding under pressure, the Mexican state sends a disturbing message: sovereignty ceases to be a guiding principle and becomes a negotiable variable. The idea takes hold that, under certain external conditions, autonomy can be pragmatically suspended without significant public deliberation. This precedent is more serious than any short-term calculations regarding bilateral relations or momentary balances.

For the Latin American left—even for those who have been critical of the Cuban government—the meaning is clear. It will not be interpreted as realism or strategic prudence, but as an abandonment of a tradition that distinguished Mexico, even in the face of openly conservative governments of the past. The loss is symbolic, but symbolic losses often have lasting and difficult-to-reverse effects.

This shift does not occur in a vacuum. It is part of a broader context in which foreign policy is increasingly being redefined by fear: fear of sanctions, fear of financial instability, fear of diplomatic discomfort. The problem is not recognizing power asymmetries—they have always existed—but rather making them the guiding principle of state action.

This is not a matter of nostalgia or ideological romanticism. It is a historical warning. Countries that relinquish their traditions of autonomy rarely easily regain the ground they leave behind.

When that happens, foreign policy ceases to be strategy and becomes mere risk management. Immediate containment is prioritized over long-term planning. Conflict is avoided, but at the cost of relinquishing a distinct voice.

History doesn’t usually judge tactical errors or decisions made under pressure harshly. But it does clearly record breaches of principle. In the long run, what will remain is not the technical explanation or the specific circumstances, but the moment when Mexico ceased to be an exception and accepted, without much resistance, the role others assigned it.

This is not a matter of nostalgia or ideological romanticism. It is a historical warning. Countries that relinquish their traditions of autonomy rarely easily regain the ground they leave behind. And when they try to do so, they often discover that the cost was greater than they initially seemed willing to admit.

-

Not By Bread Alone…

Returning to the Mesoamerican milpa agricutlural system could revitalize agriculture, while defending Mexicans and Mexico from a tangled, global necro-politics.

-

Socialism & Anti-imperialism in Mexico During the 1970s & 1980s

Widespread anti-imperialist mobilizations served as a pressure mechanism against the subservient and collaborationist policies of regional governments.

-

Iranian Ambassador Asks Mexico to Condemn US & Israeli’s Illegal Attacks

The Ambassador confirmed 106 young children were confirmed murdered after the US & Israel regimes bombed a girl’s school.