Fascism & The Popular Front: The Comintern’s 7th Congress

This article by Jaime Ortega originally appeared in the October 8, 2025 edition of La Jornada, Mexico’s premier left wing daily newspaper. The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Mexico Solidarity Project.

In the summer of 1935, hundreds of people from around the world participated in the Seventh Congress of the Communist International (CI) at the House of Trade Unions in Moscow. This organization was born in 1919 in the heat of the Russian Revolution, with the mission of establishing socialism on a global scale. Beyond that imperative, characteristic of an era in which everything was possible, it soon transformed into an instrument for managing geopolitics within the communist orbit. After the establishment of Soviet raison d’état, the CI experienced the paradox of being an organization designed to spread the revolution and at the same time a disciplined and hierarchical structure that depended, to a large extent, on the survival of a state.

By 1935, the CI was a powerful organization, coexisting and merging with other structures, such as the Peasant International, the Trade Union International, and the International Red Aid. The well-oiled apparatus, however, still depended on the political directives discussed at its famous congresses. Reaching Moscow in 1935 was not easy, but the CI’s organizational capacity allowed it to effectively constitute a global representation that could convene to decide the fate of the communist movement.

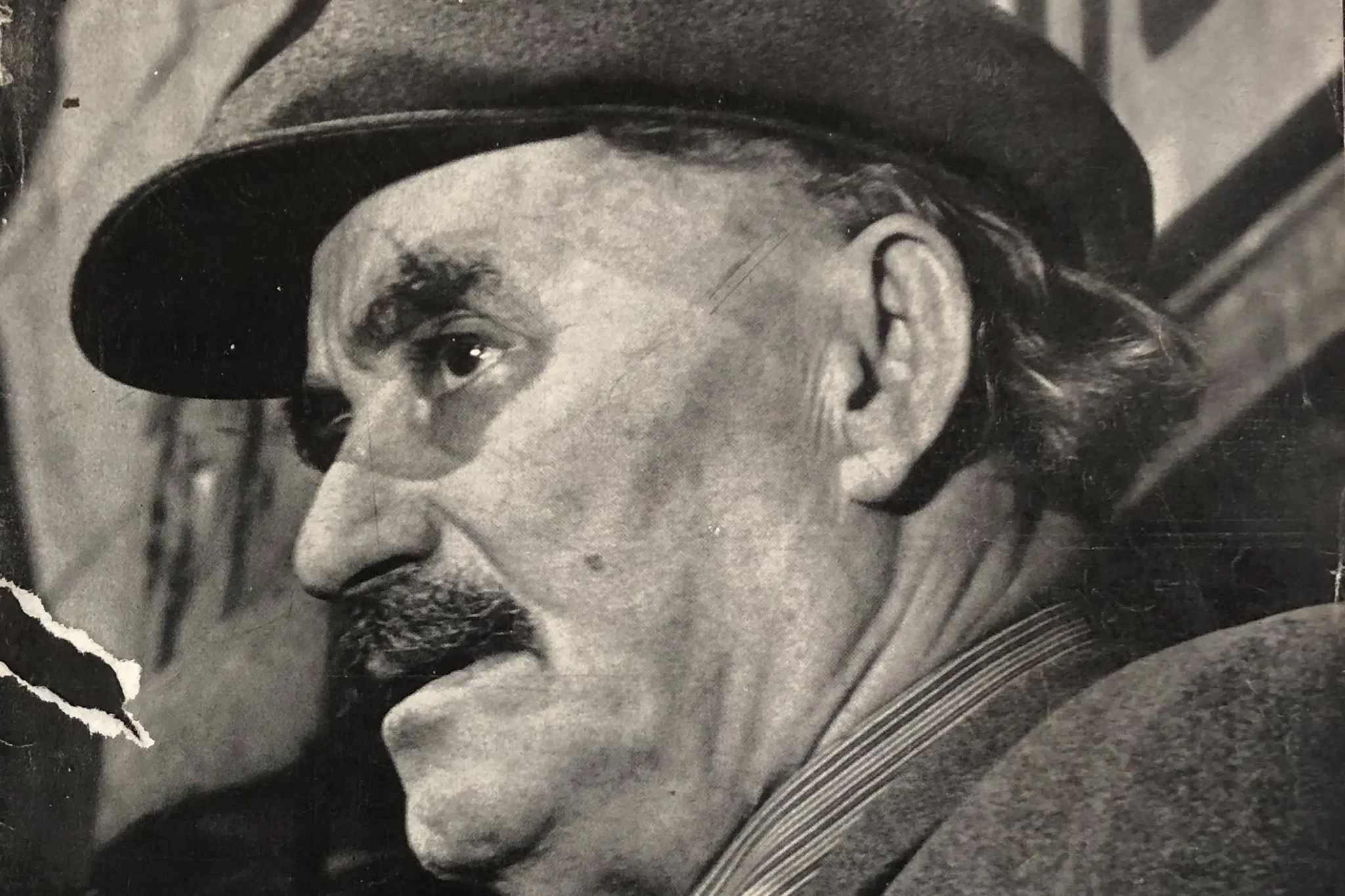

The context of that congress was overwhelming, as war was looming and fascism’s growing power grab was manifest throughout Europe, posing a threat to the socialist political order. The Seventh Congress witnessed the leading role of the Bulgarian communist culture hero, George Dimitrov, whose report outlined the politics of the following decade, and much of what was established there was transformed into a political culture that transcended time.

In his speech, Dimitrov pointed out that fascism was not a government, among others, of the bourgeoisie, since fascists had often come to power fighting against fractions of the capitalist ruling class. He pointed out the error of considering this political form as the expression of sectors of the lumpenproletariat and the petite bourgeoisie, something that Zetkin and Trotsky maintained. For Dimitrov, fascism was above all the political and power capacity of finance capital, which, while taking various forms, was distinguished by establishing a type of political monopoly, particularly “terrorist,” over the worker and peasant organizations.

After this initial characterization, he expressed concern about the phenomenon’s assessment as an “ordinary situation” of capitalism. Fascism, he argued, brought about a radical substitution of the state form typical of bourgeois society. Before this occurred, it was necessary to identify the preparatory stages of its rise in order to combat it effectively.

Nine decades after that Comintern meeting, it is worth returning to its documents, as they enrich the heritage of past anti-fascist struggles and reveal the paths, assessments, and concerns that can contribute to fine-tuning the compass for our times.

He also pointed out the urgent challenges facing fascism, especially the fact that fascism appealed to the deepest sentiments of society and even exploited pre-existing revolutionary traditions, resorting to “skillful anti-capitalist demagoguery.” In response to the “unacceptable” dismissal of the fascist danger by those who considered it to be just another routine expression of the domination of capital, Dimitrov warned of the need for a change of strategy.

This entailed an insistent critique of the lukewarm social democratic stance of the time, as well as a self-criticism of the communists’ position. Thus was born the Popular Front policy, which required the promotion of far-reaching political alliances. This called for a united front tactic between organizations, labor movements, and peasant and petty-bourgeois parties, with the goal of defending the everyday interests of the working classes.

All of this was radicalized in the “colonial countries,” where the anti-imperialist framework was to be the heart of the Popular Front. Rereading Dimitrov’s report today is thought-provoking, as it demonstrates a complex understanding of the fascist phenomenon and legitimately articulates a political and democratic response, such as the Popular Front. From that moment on, the need for the national sections to more effectively value local political traditions, especially those that could be appropriated in a revolutionary context, was established.

A tension also arose between the Soviet example, with all its aura of success, and the need to consider the necessity of democratic achievements in each national space. Under these premises, the very existence of the organization was questioned, as it was ultimately in national circles that political action was decided. Nine decades after that meeting, it is worth returning to its documents, as they enrich the heritage of past anti-fascist struggles and reveal the paths, assessments, and concerns that, even in very distant circumstances, can contribute, if read with the necessary historical caution, to fine-tuning the compass for our times.

Jaime Ortega is a researcher at UAM, and author of En el medio día de la revolución.

-

Mexican Energy Dependence & Exposure

Without a planned transition, without genuine diversification, and with declining oil production that no longer guarantees its own market share, Mexico faces a scenario in which neither gas nor oil operate as strategic levers.

-

Neither Corn Nor Country

The Fourth Transformation promised food self-sufficiency for Mexico and to rescue agriculture, but heavily-subsidized US imports have never been higher, while farmers go bankrupt and the crisis reaches intolerable levels.

-

Only 32 Labour Inspectors in Mexico City for Over 460,000 Companies

Between October 2024 and August 2025, the first year of the current local administration, the Labor Secretariat carried out only 592 workplace visits.