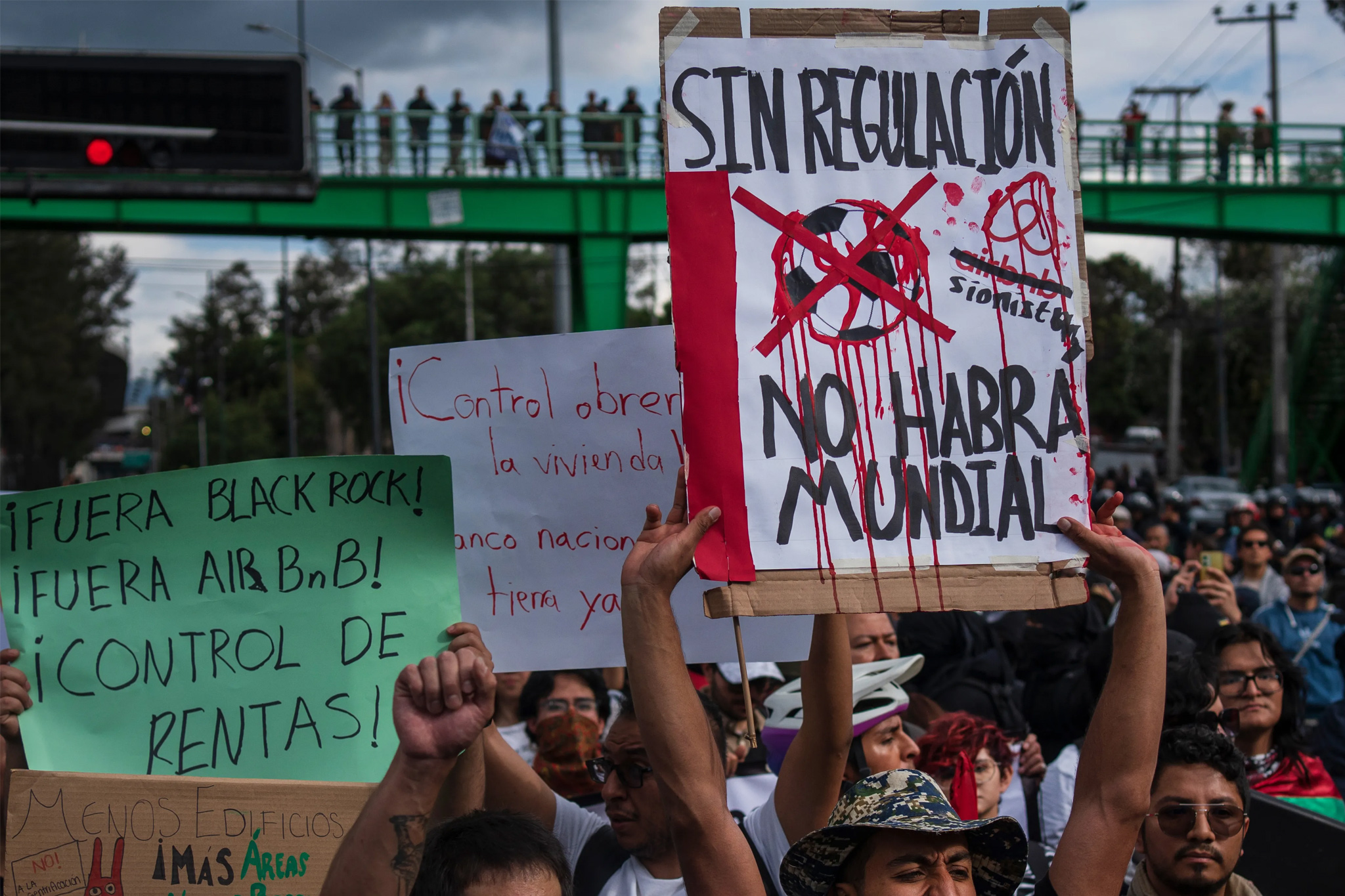

Mexico City Fails to Control Airbnb Ahead of 2026 World Cup

This article by Gerardo Jiménez originally appeared in the December 4, 2025 edition of El Sol de México.

[Editor’s note: Martí Batres, who was the interm head of government for Mexico City when Claudia Sheinbaum left to campaign for the Presidency, passed excellent legislation to control Airbnb & other rental platforms that has yet to be implemented. Hopes were high for Clara Brugada, who is the current head of government, because of her incredible work with the Utopias community centres during her time as head of government in Iztapalapa, but many of Clara Brugada’s anti-gentrification intiatives announced in July after anti-gentrification protests were already supposed to be implemented in 2024, and still remain un-implemented. A recent initiative to expropriate 400 unused properties for housing over six years is positive, but represents a drop in the bucket in one of the largest cities in the world.]

Mexico City is approaching the 2026 World Cup with an unresolved debate: whether to regulate or deregulate short-term rentals through Airbnb and other platforms. While some voices in government and the private sector are pushing to temporarily relax restrictions to accommodate the influx of visitors, the discussion has become bogged down in legal challenges, institutional inaction, and a housing crisis that has already displaced thousands of families in the capital.

Gerardo Villanueva, a local deputy from the Workers Prty (PT) who has been leading housing initiatives for 30 years as part of Movimiento Urbano Popular (Popular Urban Movement), acknowledges that there is a real debate within the Mexico City Congress: “There are those who say that we don’t have the hotel capacity to accommodate the World Cup visitors; but others maintain that we cannot relax controls because that would aggravate the real estate pressure,” he points out.

The legislator, a member of the local Public Administration Commission, recalled that the regulation approved by the capital’s government establishes a maximum of six months of lodging per year per property, a figure that – he assures – “is even more permissive than that of other countries.”

More than 23,000 families—some 100,000 people—have left their neighborhoods due to increased rents, says Workers Party Gerardo Villanueva.

He believes that proposing a relaxation of the rules under the argument of a world tournament is “a false debate with media appeal.”

Although Airbnb and dozens of hosts have filed injunctions that have halted the implementation of the 50 percent restriction on available nights and the mandatory host registry, several definitive suspensions have left the city in a legal limbo: there is no clarity on limits, no one is monitoring the use of properties, and the digital registry that was supposed to be operational since 2024 remains inactive.

Neighborhood organizations also warn that the city government failed to implement the registry and have also taken legal action.

Villanueva emphasized the root of the conflict : the brutal increase in housing costs. “Landowners prefer to rent through apps because they pay better, which pushes young people, families, and senior citizens out of their neighborhoods. In Condesa, rents were already high, and with Airbnb, they skyrocketed even more,” he stated.

For the legislator, the priority must be protecting the possibility for people to continue living where they always have. And although he acknowledges that the World Cup will generate economic benefits , he insists that “it’s only five matches and two months; you can’t dismantle a housing policy because of a temporary event.”

Gentrification Has Caught Up With Us

Gentrification, he admits, reached and overwhelmed the institutions. “Between 2012 and 2018 there was a corrupt government that dismantled housing finance, then came the 2017 earthquake and the COVID crisis. All of that directly impacted the State’s capacity to build social housing,” he explains.

This was compounded by the misappropriation of reconstruction funds by former city officials, which paralyzed public investment for years. With a weakened Housing Institute (INVI), the growth of short-term rentals accelerated the silent displacement of residents.

Today, the displacement is tangible: more than 23,000 families—some 100,000 people—have left their neighborhoods due to increased rents, the legislator says.

Many of those affected, he adds, first moved to Iztapalapa and then to the State of Mexico; others keep their voter registration in their original borough “out of nostalgia,” even though they no longer live there. Villanueva warns that this phenomenon is different from the traditional housing shortage: it is a case of displacement due to market pressure, amplified by the arrival of digital nomads and real estate speculation.

The current housing deficit in Mexico City amounts to 600,000 units, according to data from INEGI and specialized platforms. “These figures even fall short,” admits the congressman.

Although the city government is planning 200,000 housing initiatives —ranging from home improvements to new units—the challenge remains monumental: nearly half of the city’s residents live in rented or borrowed accommodations. “People are getting sick from paying rent. The month feels like it has two weeks,” summarizes Villanueva, who insists that the only viable solution is to build more housing and stop the displacement of residents.

-

Veracruz: Oil Spill Victims Complain Of Insufficient Action by State Government

Residents of Pajapan, who live around Laguna Ostion, demand that the authorities take prompt intervention to solve the hydrocarbon spill in the southern part of the state of Veracruz.

-

San Luis Potosí Goodyear Workers Threatens Strike After Salary Increase Refusal

While Mexico’s general minimum wage has had a real increase of 116% in the last seven years, SITGM workers have received only 15.2% increases in the same period.

-

FIFA’s Cola Cup & Dystopian Horror

The World Cup’s arrival in Mexico is a stark illustration of the absurdity of the world we’ve reached thanks to the power of large corporations; of the crisis of our current civilization, a society trapped in a power economy, manipulated by addictions.