Cárdenas & Cuba: The Torrent of Solidarity

This article by Jaime Ortega appeared in the February 2nd, 2026 edition of La Jornada, Mexico’s premier left wing daily newspaper.

The bond between Cuba and Mexico is deeply rooted. Sympathy for the independence and revolutionary movements on the island is as old as the movements themselves. This sentiment was strengthened by the Mexican exiles, at different times, of the “three M’s”: Martí, Mella, and Marinello. They were joined by other figures such as Raúl Roa, who in his Return to the Dawn defined Morelos as “a great civil hero of Mexico,” Juárez as “great for being a hero, a revolutionary, and an indigenous person,” and Cárdenas as “the most formidable leader of the Mexican Revolution.”

In the Communist Party of Mexico, the figure of the Cuban [Julio Antonio] Mella was, of course, legendary. His assassination in the streets of the Juárez neighborhood made him an icon for communists in both nations. Benita Galeana’s testimony has revealed the clandestine and heroic way in which Mella’s ashes were smuggled out of Mexico in 1933. Meanwhile, in 1934, the Mexican section of the International Red Aid (IRA) worked alongside the League of Revolutionary Armed Forces (LEAR) and the Hands Off Cuba campaign, demanding non-intervention on the island, based on the similarity of the aggressions: in Mexico in 1914 and on the island two decades later. Other Cuban voices and writers made their presence felt in the Mexican cultural scene; one significant figure was Loló de la Torriente (cousin of the legendary journalist Pablo de la Torriente, who died in the Spanish Civil War), a frequent contributor to the newspaper El Machete.

However, of all the figures who shared a passion for solidarity with the Cuban people, General Cárdenas is undoubtedly the most important, and rightly so. It is not surprising that from 1936 onward, numerous expressions of friendship were extended from the island toward the revolutionary actions of the man from Michoacán, since by the time the general assumed the presidency, the Cuban Revolution of 1933 had already overthrown the infamous Gerardo Machado. An episode recounted by Ángel Gutiérrez, among others, in Lázaro Cárdenas and Cuba sheds light on the mutual commitment between the Cuban revolutionaries and the popular Mexican leader.

The fact that the two countries immediately south of the border with the United States had to undergo several revolutions to establish their sovereignty is indicative of the nature of their nationalism: defensive and united in the face of aggression.

The most intense period was in 1938, when, following the oil expropriation, numerous articles appeared honoring and defending both the act and the Mexican President. In addition to Juan Marinello, well-known to Mexicans, Salvador Massip, José Luciano Franco, and Ángel Augier spoke out in defense of Mexican sovereignty. Franco stated that Cárdenas’s actions had broken “with the inferiority complex imposed on the countries of our America by financiers.” Words turned to action, and a group, including Carlos Rafael Rodríguez, head of the Friends of the Committee for a Tribute to Mexico, set about contacting the Mexican ambassador on the island. Marinello, for his part, approached Francisco J. Múgica to request that the president address the Cuban people. Múgica convinced his former comrade-in-arms, and Cárdenas agreed.

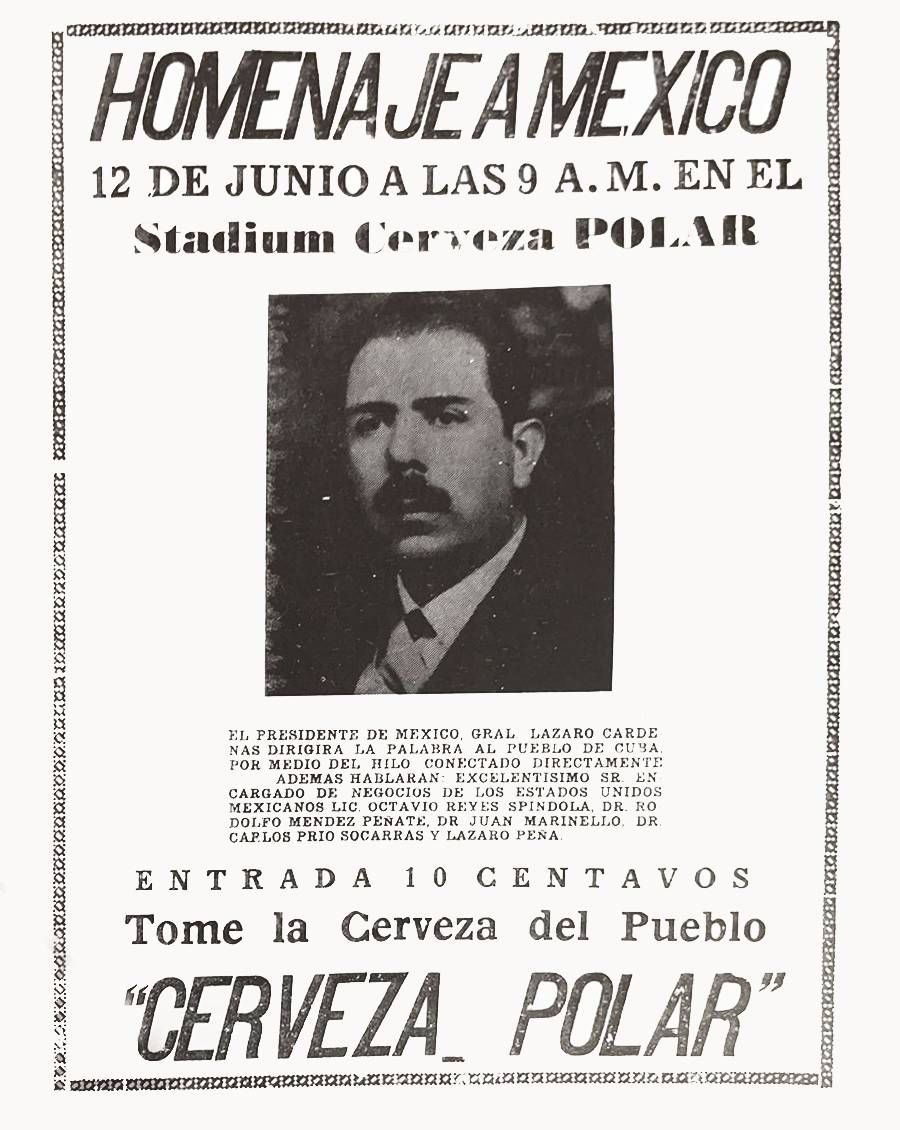

Thus, on June 12, 1938, a large rally in support of Mexico was held at La Polar Stadium in Havana, attended by thousands. Admission was 10 cents, and the proceeds were earmarked to support the expropriation, making it reasonable to assume that part of the nationalization was paid for with the sweat of the Cuban people. Cárdenas delivered a radio address from Tampico, stating that the “political and spiritual” autonomy of the Latin American republics would be crippled “if a concept of solidarity among their peoples is not affirmed.” Carlos Prío Socarrás, Lázaro Peña, and Marinello himself also spoke at the Havana stadium.

The Cuban rally was one of the most significant demonstrations in support of the oil expropriation outside of Mexico, and the island was among the countries that most strongly supported it in the face of the oil companies’ boycott.

It is no coincidence that, decades later, in 1961, a group of intellectuals—among them another friend of revolutionary Cuba, Revueltas—published an article in the newspaper Hoja Revolucionaria with the headline: “Not sending oil to Cuba is betraying the oil expropriation.”

The fact that General Cárdenas was no longer in power did not prevent him from expressing his firm support for the cause of the sister nation, a cause that found its epicenter in the Latin American Conference for National Sovereignty, Economic Independence, and Peace, which was attended by, among others, Vilma Espín.

Many years after General Cárdenas’s death, in 1995, Commander Fidel Castro evoked the Michoacán native while attending an event in the Plaza de la Revolución, where he remembered him “struggling with his usual sobriety, deeply moved and with an exalted spirit. His speech was a torrent of revolutionary and Latin American fervor.” The fact that the two countries immediately south of the border with the United States had to undergo several revolutions to establish their sovereignty is indicative of the nature of their nationalism: defensive and united in the face of aggression.

-

People’s Mañanera February 9

President Sheinbaum’s daily press conference, with comments on scholarships, return of mining concessions, PRIAN exposed, Bad Bunny Super Bowl, and aid to Cuba.

-

8 Million App Users, TV Soap Opera Ad… & the PAN Still Can’t Find New Members

In Mexico, where political parties are currently publicly financed, the right wing PAN has spent a staggering amount during its lackluster recruitment drive.

-

Mexico’s National Film Archives Workers Demand Dignity

“Our struggle is legitimate; we are not asking for privileges or luxuries, only better working conditions and job security. We also seek dialogue. This situation has become unsustainable.”