1977’s Electoral Reform & The Left

This article by Jaime Ortega originally appeared in the August 19, 2025 edition of La Jornada, Mexico’s premier left wing daily newspaper. The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Mexico Solidarity Project.

The demand to establish proportional representation in the legislature is almost as old as what was once called the post-revolutionary regime. As has been written elsewhere in La Jornada, Narciso Bassols—a two-time candidate for deputy (1943 and 1948), both of which were the victim of fraud—was one of the first to raise this demand. The slogan was inherited as part of the marginal, but ongoing, opposition electoral campaigns. It was presented in 1952 by Lombardo Toledano in the Popular-Communist coalition, and in 1958 it was part of the program of the Partido Comunista Mexicano-Partido Obrero Campesino de México alliance with Miguel Mendoza López as its candidate. That year, the Popular Party, despite supporting López Mateos, also incorporated the representative dimension into its program. Thus, it is far from being an innovation for Mexico, from Federico Reyes Heroles [former Secretary of the Interior who oversaw the political reforms of 1977 – ed], the statesman who received Enrico Berlinguer by declaring himself a reader of Gramsci.

However, looking at the 1977 reform process as it is being discussed in public debate must move beyond a purely presentist concern. Allow me to turn my gaze to a key moment in electoral terms, the 1988 election. This is so because, in both the 1979 midterm elections and the 1982 presidential elections, there was no possibility of truly challenging the ruling party for power. Political reform had its first test of fire when a significant social political force managed to summon the notion of democracy as an exercise in majorities. To understand that moment, I return to some of the interviews conducted during 20 Years of Research: Testimonies from the Left, conducted by Eduardo del Castillo with political leaders in 1991.

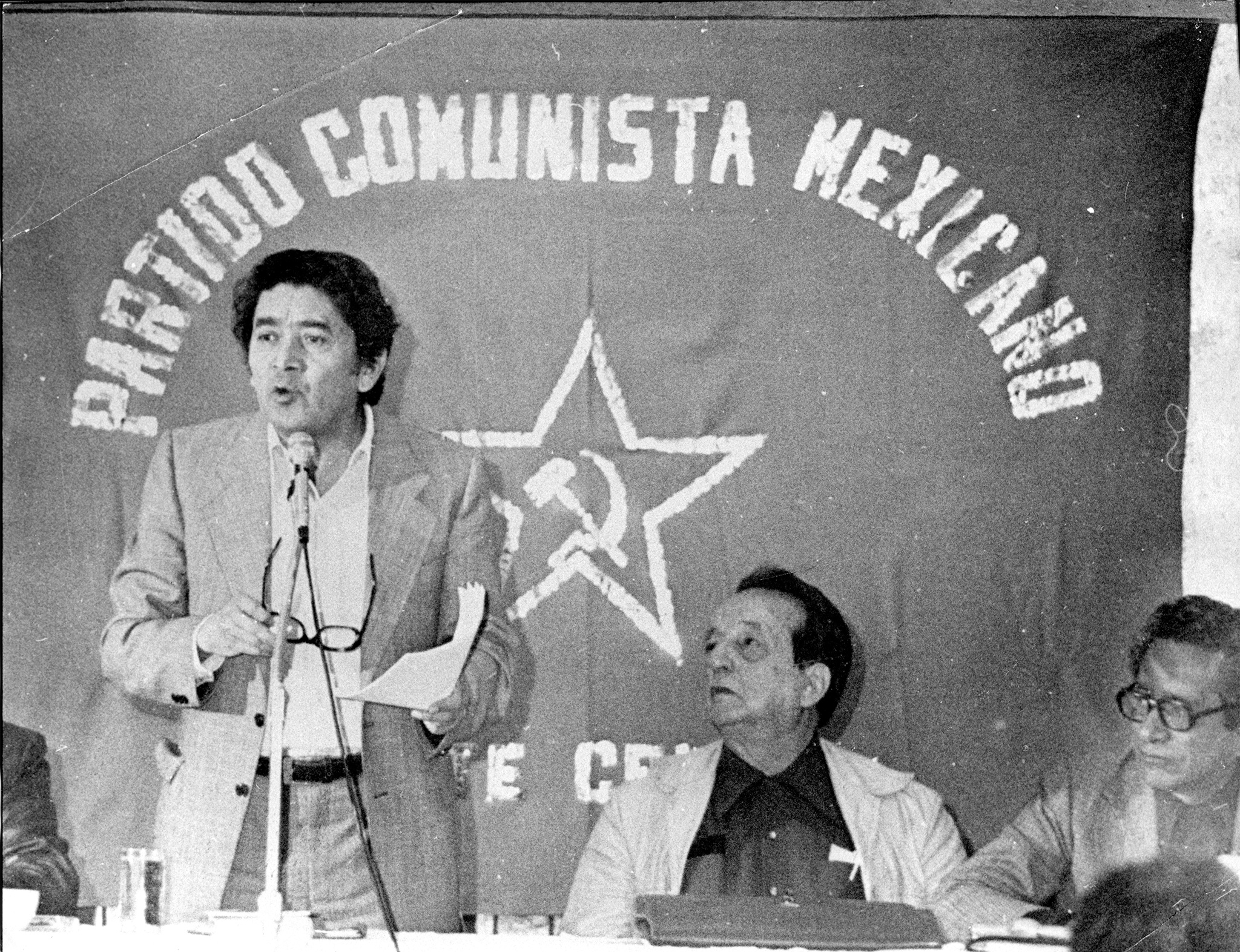

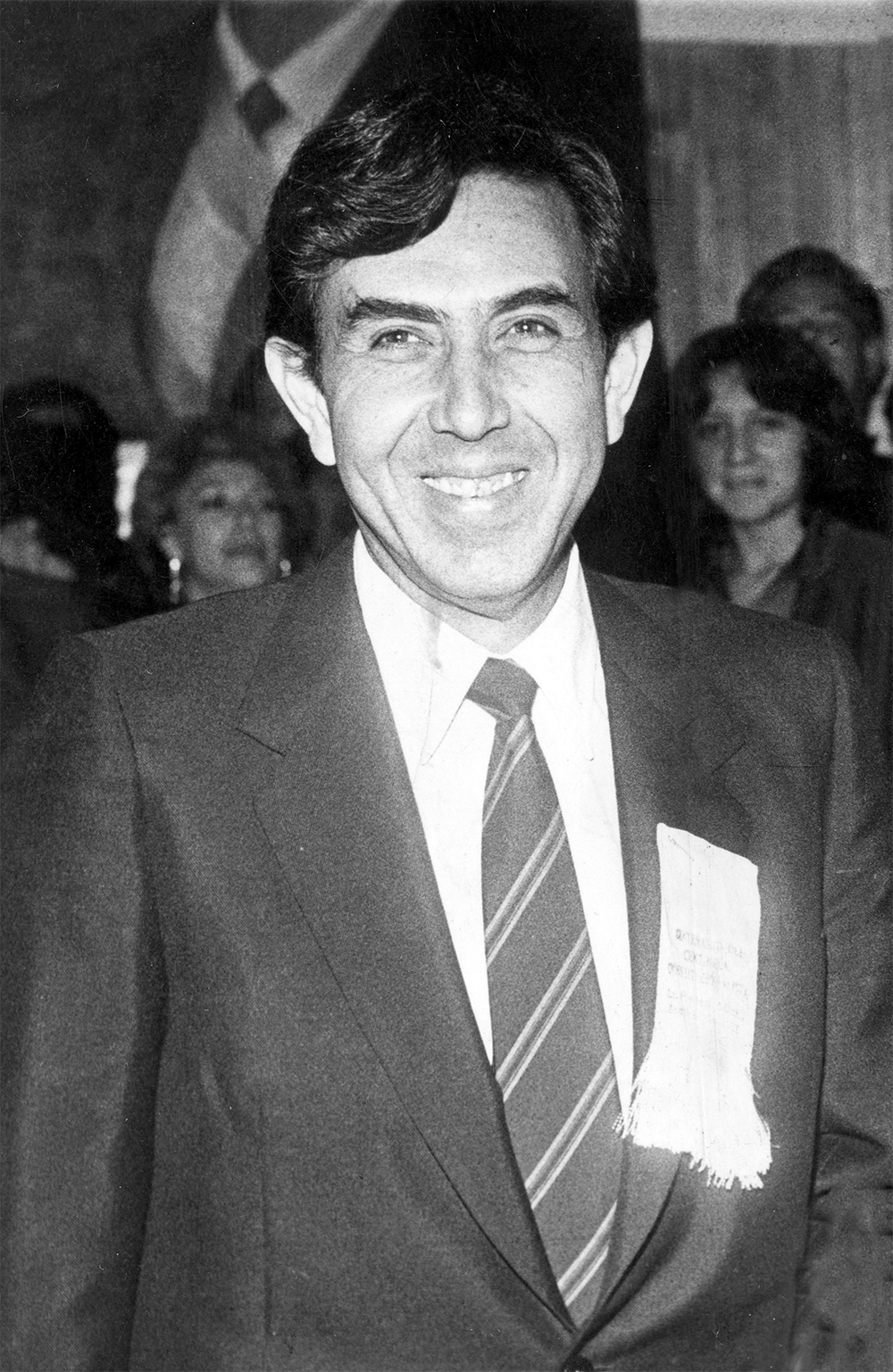

In these discussions, Raúl Álvarez Garín stated that “the purpose of political reform is to isolate and separate” the political forces, even though it had allowed for a previously unprecedented parliamentary experience. For his part, Valentín Campa [founder of the Unified Socialist Party of Mexico, 1976 Presidential candidate for the Mexican Communist Party – ed] pointed out that “the government did not want to make these concessions and offered maximum resistance.” Meanwhile, Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas [1988 Presidential candidate for the left – ed] himself, who was subject to electoral fraud, considered that: “These were limited reforms, reforms that did not seek to pave the way for a true democratization of the political regime, and that at no point even considered ending the political dominance of the state party.” For Heberto Castillo [politician and engineer who became active in Cárdenas’ National Liberation Movement, the ’68 student movement, gradually moving towards more social democratic politics – ed], this was “an adjustment, not a realization of anything,” referring to the failure to achieve the major demands of 1968. For his part, Pablo Gómez [who has been appointed by President Claudia Sheinbaum to take charge of the electoral reform process – ed] stated that the reform did not “completely change the political situation, but, although very partial, it is a reform.” Arnoldo Martínez Verdugo [SecGen of the Mexican Communist Party from 1963-1981, who oversaw its 1979 election campaign where it won 18 seats, later founder of PSUM – Unified Socialist Party of Mexico – ed] stated that it was a “very limited reform,” with the central issue being the issue of party registration. Gilberto Rincón [one of the founders of the PRD, Party of the Democratic Revolution from which Morena would emerge as it slid rapidly to the right. As of 2024, it has lost its registration as a political party – ed] similarly stated that “it was very limited,” but that the most important aspect was the registration of the PCM.

Today, it’s argued that the core of the 1977 reform was proportional representation alone, and the entire discussion given in the hearings by the opposition parties, which referred to the complete democratization of the state and its ties to society (including the rural and working world), as well as the full enjoyment of rights and freedoms, is ignored. This operation elides the fact that, although the “minorities” found some possibility of parliamentary praxis, the reality is that the contest for power remained closed.

For this reason, after 1988, the main actors would be skeptical and critical of the reformist crystallization. Specifically at that time, the mechanism of proportional representation took a backseat if the ability to recognize the rights of organized political forces (the problem of registration, especially the concept of “conditioning”) and, above all, effective respect for the vote were not addressed. And it was the popular upsurge of 1988 that demonstrated that, beyond parliamentary representation, there were many outstanding issues. Even today, one could point to the profound influence of state agencies (despite the autonomy of the body in charge) over political parties, understood as social expressions, and, above all, the complexity of forming new groups.

Having reopened that discussion, it is important to look at the whole (with criticisms and reservations, of which there were many) and not just start from fragments. If we understand that democratization is always an unfinished and perfectible process, it is pertinent to imagine taking steps forward and formulating new forms of political representation that allow for the democratic exercise of majorities and guarantee effective conditions for the contestation of power.

Jaime Ortega is a researcher at UAM, and the author of La raíz nacional-popular: las izquierdas más allá de la transición.

-

People’s Mañanera February 9

President Sheinbaum’s daily press conference, with comments on scholarships, return of mining concessions, PRIAN exposed, Bad Bunny Super Bowl, and aid to Cuba.

-

8 Million App Users, TV Soap Opera Ad… & the PAN Still Can’t Find New Members

In Mexico, where political parties are currently publicly financed, the right wing PAN has spent a staggering amount during its lackluster recruitment drive.

-

Mexico’s National Film Archives Workers Demand Dignity

“Our struggle is legitimate; we are not asking for privileges or luxuries, only better working conditions and job security. We also seek dialogue. This situation has become unsustainable.”