A Great American

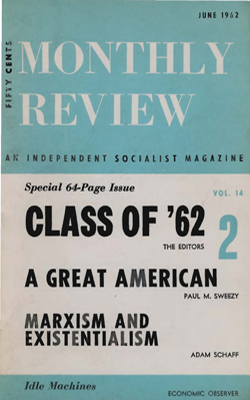

This interview of the 51st President of Mexico, General Lázaro Cárdenas del Río, by Paul M. Sweezy originally appeared in the Volume 14, No 2 issue of Monthly Review (June, 1962). We thank Monthly Review for the permission to reproduce this invaluable interview, which was recently referenced in this La Jornada column by Jaime Ortega, and encourage you to subscribe to the independent socialist magazine, a vital anti-imperialist and Marxist voice in the English language since 1949.

Most North Americans-to use the Latin American expression for the people of the United States-have probably never heard of Lázaro Cardenas. And most of those who have heard of him probably think of him as a has-been who as an old man has become either a tool or a dupe of the Communists.

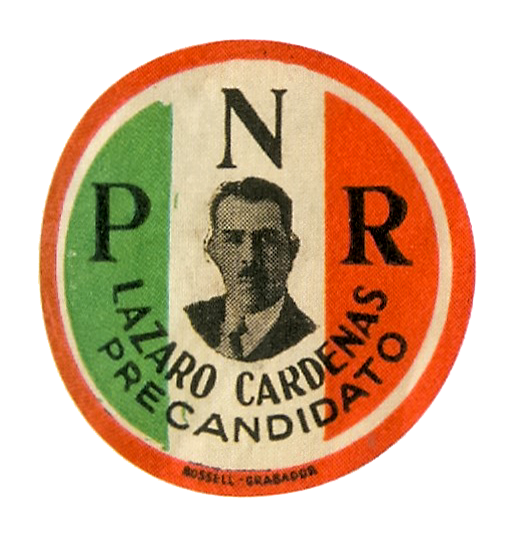

They could not be more wrong. The former President of Mexico (1934-1940) is a power not only in Mexico but throughout Latin America. Far from being a dupe or tool of anyone, he is a man of massive strength and independence. He is not even an old man. Relatively young when he was elected President one year after Franklin D. Roosevelt took office in the United States, Cardenas in his mid-sixties is as vigorous and active as many a man ten years or more his junior.

Cardenas’s position in the Mexican political scene is unique and likely to remain so. Political power in Mexico is monopolized by the Party of Revolutionary Institutions (PRI) which completely dominates the government, the trade unions, and the national peasants’ organization. As head of the big TVA-like project which centers on the Balsas River and reaches into eight states, Cardenas holds one of the most important positions in the Mexican government. At the same time as the inspirer and spiritual leader of the newly formed National Liberation Movement, he is the central figure in the only opposition which is potentially capable of transforming and revivifying Mexican political life. He is able to play this dual role only because of his commanding prestige in the country at large, and especially among the peasants. One of the great actors in the historical drama of the Mexican Revolution, Lazaro Cardenas may yet hold in his hands the keys to his country’s future.

As an interested observer of Mexican affairs for more than a quarter of a century, I have long been an admirer of General Cardenas and hoped some day to have the honor of meeting him in person. When I was invited last summer to deliver three lectures at the School of Economics of the National University, it seemed that the opportunity might be at hand, but the General spends much of his time outside the capital and it proved impossible to find a date when he was both available and free. Invited again by the School of Economics to come to Mexico, this time to serve as a member of the examining board of a candidate for the degree of Licenciado (roughly comparable to our Ph.D.), I traveled to Mexico City late in April. General Cardenas was in the capital and readily agreed to my request for an interview, which took place on April 25th in the office of his house in Lomas de Chapultepec on the outskirts of Mexico City. I was accompanied by Alonso Aguilar of the faculty of the School of Economics who studied in New York at Columbia during the 1940’s and is now a member of the sixman directing committee of the Movement of National Liberation. Senor Aguilar acted as interpreter.

I of course knew of General Cardenas’s role in Mexican history and was aware of his pre-eminence in the eyes of his countrymen. I soon discovered, however, that I was very far from appreciating his full stature. It is a fair generalization, I suppose, that most people stop developing at a relatively early age. And men or women who reach a peak of achievement while they are still young and vigorous are quite likely in later life to look back on their lives with nostalgia, finding anti-climax in everything that has occurred since their days of glory. For these and related reasons, one expects a man in General Cardenas’s position to be more oriented to the past than to the present or the future; one expects his reminiscenses to be more interesting than his prognoses. Coming to the interview with preconceptions of this kind, I was unprepared to discover the real Lazaro Cardenas of 1962. And as I sat, fascinated, listening to him discuss the great issues of the day, especially as they affect his country and mine, I came gradually to the realization that I was in the presence of one of the really great figures of American history-a man who one day will surely be ranked with Bolivar and Washington, with Juarez and Lincoln, with Fidel Castro and Franklin D. Roosevelt in the pantheon of the Americas.

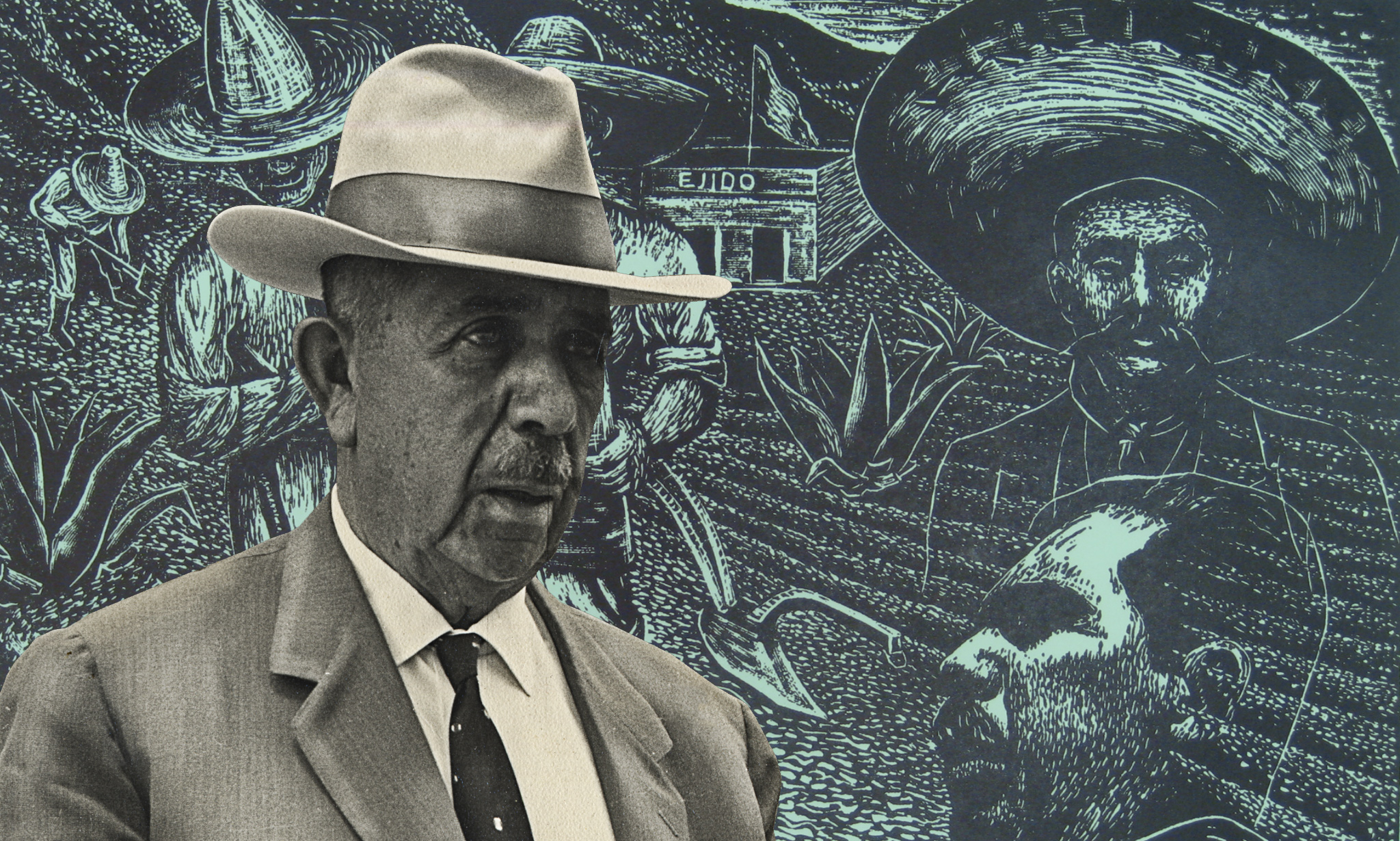

Lomas de Chapultepec is a relatively new residential area where much building is in evidence; the houses, at least from the outside, are not unlike what one might see in an upper-class section of San Francisco or Los Angeles. General Cardenas’s house is one of these, outwardly much like its neighbors. There were a number of people outside and in the courtyard, evidently a part of the General’s official establishment, but the atmosphere was quiet and unhurried. The office into which we were shown on arrival is well appointed and in excellent taste. General Cardenas entered through a door that opens on a garden. At no time during the nearly two hours we were with him was one conscious that he is a busy man with many and varied responsibilities. No telephone rang, no secretary entered.

General Cardenas, of heavy set and medium height, looks for all the world as though he had just stepped out of one of Rivera’s murals depicting the panorama of Mexico’s turbulent history. He speaks in a low voice without rhetorical mannerisms. His expression is mostly quiet and attentive, even immobile; but when he talks, an elusive smile lights up his olivegreen eyes. Though he doesn’t look at all like him, I was somehow reminded of Einstein. The modesty and deep humanity of the man are, as it were, a part of his appearance, and I suppose that this is what makes him look like Einstein after all.

I had indicated in advance that I would especially like to get his views on the Alliance for Progress, and he quickly expressed his agreement. But first he wanted to talk about Cuba, partly perhaps because, having read Leo Huberman’s and my book Cuba: Anatomy of a Revolution, he knew of my great interest in the subject, but even more, I suspect, because he wanted to express to whatever audience he might reach through this interview his complete and unreserved solidarity with the Cuban Revolution and its leaders. There was no trace of holding back, of diplomatic circumlocution. The Cuban Revolution was right and good because it was undertaking essential social transformations, because it enjoyed the wholehearted support of the popular masses, and because its leaders were honest and dedicated men. I asked him whether Fidel’s December declaration of adherence to Marxism-Leninism had given him any feelings of doubt or foreboding. Not at all, he said. Fidel had come to this position through experience, and in saying so openly before the world he was strengthening, not weakening, the Cuban Revolution.

I did not wish to question General Cardenas about his personal political views, but I received the strong impression that experience had led him to essentially the same position as Fidel’s. It is surely food for thought-especially, one would hope, in Washington-that the two greatest statesmen of contemporary Latin America, men who were brought up entirely within the confines of the Western democratictradition and fought to the utmost to realize its ideals in practice-that such men have been led by their own full and often bitter experience to adopt the world outlook of revolutionary Marxism. Could there be more eloquent testimony, I thought as I listened to him speak, to the truth and universality of Marxism in the 20th century?

I asked General Cardenas if he thought any Latin American government would dare to support openly a new U.S. attempt to overthrow Castro by armed force. He replied that there were undoubtedly several that would like to but that if they did they would not only face the overwhelming opposition of their own people but would probably find themselves threatened from neighboring countries as well. Many people from all over Latin America, he said, would sacrifice their lives in defense of Cuba even if military defeat were absolutely certain. Statements like this reflect the fact that in relation to the great issues of our time, the boundaries between Latin American countries mean very little. All Latin Americans, revolutionary and counter-revolutionary alike, feel that what happens in Cuba concerns them almost as much as it does the Cubans. As the title of a book just published in Mexico puts it, Cuba no es una isla.

Next we turned to the Alliance for Progress. General Cardenas began by saying that it was quite possible that President Kennedy and others in the U.S. government are sincere in what they say about the Alliance for Progress. That is not the point. The words sound very good; the trouble is that they do not agree with the facts. There has been no progress, and nothing is being done or planned that can bring any progress. These are the facts: they are known to everyone in Latin America. The conservatives who support the Alliance for Progress do so because it means loans from the United States. They know, and everyone else knows, that the loans come with strings attached, that their purpose is to reinforce the existing social structure, not to create the conditions necessary for progress.

I asked him whether this contradiction between words and facts, so obvious to everyone, doesn’t generate enormous cynicism; whether the blatant lack of correspondence between what is said and what is done doesn’t lead to distrust of words in general. He agreed that this is indeed the case. The peoples of Latin America, he said, observe that the views and attitudes of the United States agree fully with those of their own conservatives, and they know from long experience that the latter are the enemies of progress. How can they help concluding that the U.S. is also the enemy of progress? Was he not saying, I asked, that the name should be changed to the “Alliance against Progress”? He nodded assent.

There is in operation, he went on, a vicious circle. The governments of Latin America for the most part do not have the confidence of their own peoples and are not even trusted by the U.S. It follows that loans to them must be accompanied by close supervision. And this in turn offends the dignity and honor of the people who become all the more alienated from and hostile to their governments.

At this point I asked General Cardenas if he thought it was possible for the United States to change its policies in such a way as to bring real assistance to the countries of Latin America. I mentioned the extent to which U.S. manpower is unemployed and productive capacity idle, estimating that if a real effort were made production could easily be doubled in a short time. I said that the situation seemed to many of us in the United States a disgrace at a time when so many of the people of the world are so poor and hungry. Did he think that there was any possibility that a relationship with Latin America (and other underdeveloped areas) could be worked out that would permit at least some of this unused productive power to serve the needs of the underprivileged?

It is easy to answer such a question with glib generalities about the need for a change of heart in Washington. Present disastrous trends can be attributed to faulty knowledge or neglect, and the leadership of the U.S. can be exhorted to mend its ways. We hear such diagnoses and prescription from our own liberals every day of the week. But an answer of this kind apparently never even occurred to General Cardenas. Rhetorical eloquence and paper schemes for reforming the world are simply not in his line. He is interested in knowing the truth and facing up to it. Instead of spinning fantasies about what the U.S. might conceivably do, he began by emphasizing what it actually is doing. It is playing a negative role, not assisting development but putting a break on development. And the reason is not the bad will or evil intent of U.S. policy-makers but the structure of U.S. society. Those who govern an imperialist country, he was saying in effect, will act like imperialists, and it is vain to expect them to do otherwise.

Those who govern an imperialist country will act like imperialists, and it is vain to expect them to do otherwise.

This does not mean that General Cardenas is at all inclined to a fatalistic acceptance of the present pattern of relations between the United States and Latin America. Like almost everyone else in Latin America, he expressed bitterness at the low and in many cases declining prices which Latin America receives for its exports. He deplored the lack of understanding between people north and south of the border. Many people in the U.S., he said, seem to think that all Mexicans are lazy. They ought to know better. Don’t many thousands of Mexicans go to the States every year to work on farms and doesn’t everyone know that they work very hard indeed? If North Americans understood Latin America better, they would certainly bring pressure on their government to adopt more sensible policies. But he had no high expectations along this line. About the most one could hope for would be that politically the U.S. would leave Latin America alone, and economically the two areas would trade more or less normally. Assistance without strings attached would be fine, but it was unlikely.

I asked General Cardenas whether he thought that, if the United States would leave Latin America alone, revolution by peaceful, democratic means might be possible in some countries. His answer was prompt and emphatic: “No doubt about it.” Keeping the present oligarchies in power cannot and will not maintain order; quite to the contrary, it will promote disorder and bloodshed. It would be vastly better if the United States would leave Latin America alone to follow ‘its own course: without U.S. support, the position of the oligarchies would be hopeless and they would be forced to give way before popular pressures. Instead, the U.S. follows exactly the opposite course-organizing police repression, sending in money to spread corruption, building up bogeys to scare and divide people, employing the CIA to undermine and overthrow democratic movements and governments. And all of this, General Cardenas remarked sadly, is not even in the interests of the United States: in the long run, the United States has far more to gain from decent governments and peaceful social reform in Latin America than from bloody revolutions and civil wars.

I raised the question whether ruling classes in decline could ever be expected to understand their real interests, and this led into a discussion of the general outlook for the world as a whole. Here, as elsewhere, I found that General Cardenas had very clear and firmly held views. He expects that the Soviet Union and China (he always spoke of them together) will outstrip the United States in economic development in the years ahead, and that the underdeveloped countries will follow in their footsteps, simply because there is no other way to solve their problems. Already, the military strength of the socialist countries is so great that the United States could not possibly launch and win a war against them. For this reason, he does not believe that there will be a war. He thinks that some agreement between the United States and the Soviet Union (and China) is likely, and he hopes that a similar agreement between the United States and Latin America will eventually be possible. If only the United States-and here I got the impression that he was thinking of the people rather than the government-would see its own interests! Because he hopes for this agreement so fervently, and because he puts more trust in peoples than in rulers, he feels that it is most important that there should be more and ever more understanding of Latin America in the United States.

I asked whether he didn’t think it possible that the ruling class in the United States would refuse to accept eclipse, that sooner or later it would blow up the world rather than allow it to develop along the lines he had sketched. He didn’t pretend to know. “You know your own magnates better than I do,” he said. But I gathered that he didn’t really believe in such a possibility. He understands the character of the age we live in with an astonishing clarity and sureness; he knows its seemingly insuperable problems, its incalculable dangers. But his commitment to humanity and his love of life are much too deep to allow him to believe in ultimate, absolute catastrophe. “In spite of all,” he said, “we must be optimistic about the future.”

With these words the interview came to an end. Whenever I feel discouraged by defeats or overwhelmed by the onrush of events, as surely we all must from time to time, I am going to remember them. And I am going to remember the quiet and gentle, but above all strong, man who uttered them. He is one of the great Americans of our time; his example can and should be an inspiration for all Americans whether they happen to live north or south of the Rio Grande.

-

People’s Mañanera February 9

President Sheinbaum’s daily press conference, with comments on scholarships, return of mining concessions, PRIAN exposed, Bad Bunny Super Bowl, and aid to Cuba.

-

8 Million App Users, TV Soap Opera Ad… & the PAN Still Can’t Find New Members

In Mexico, where political parties are currently publicly financed, the right wing PAN has spent a staggering amount during its lackluster recruitment drive.

-

Mexico’s National Film Archives Workers Demand Dignity

“Our struggle is legitimate; we are not asking for privileges or luxuries, only better working conditions and job security. We also seek dialogue. This situation has become unsustainable.”