Fears Anti-Monuments Could be Removed in Mexico City Before World Cup

This article by Juan Carlos Rodríguez originally appeared in the February 19, 2026 edition of El Sol de México.

Social organizations and human rights groups are on alert so that the Mexico City authorities do not take them by surprise as the World Cup approaches.

Four months before the start of the World Cup, among groups that defend the right to memory, the version circulating is that the capital’s government will seek to hide or remove the anti-monuments in an effort to “clean up” the urban environment.

Although the head of government, Clara Brugada, has said that she does not plan to remove the spaces designated for protest, the groups believe that the strategy may be indirect: to order the structures to be vandalized and thus have the pretext to move them.

“It is so real that the removal of the anti-monuments is actually happening,” said a spokesperson for the organization La Ruta de la Memoria, responding to an email sent by El Sol de México.

“We have information that Clara Brugada’s advisory team has mounted a dismantling operation and passed it off as acts of vandalism,” the informant added.

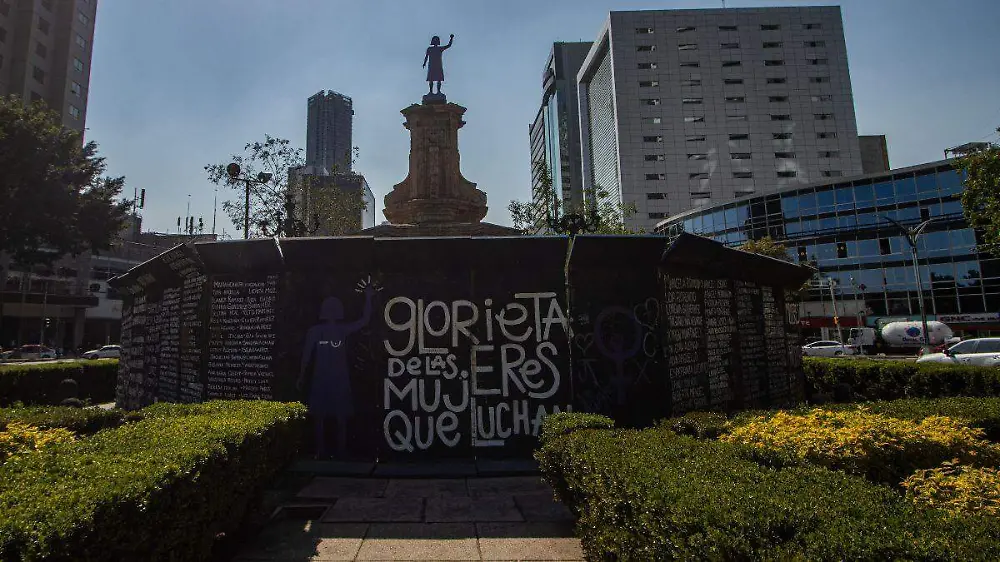

During a tour of the anti-monuments placed on Paseo de la Reforma and Avenida Juárez to assess their physical condition, it was observed that the one showing the greatest deterioration is the Glorieta de las Mujeres que Luchan (Roundabout of the Women Who Fight), located where the Columbus monument used to be.

Four of the panels surrounding the memorial , which display photographs and information about groups fighting against violence against women and enforced disappearances, are broken. In addition, some of the slogans painted on the metal fences surrounding the main structure show signs of attempts to erase them with some type of solvent.

Another anti-monument that has been vandalized is the one commemorating the 43 missing students from Ayotzinapa, located at the intersection of Reforma and Bucareli. The planters surrounding the structure are filled with accumulated trash, and the portraits of the students printed on canvas have been torn down.

The only memorial where people are guarding its safety is the so-called anti-monument, located on Avenida Juárez, across from the Palace of Fine Arts. The metal structure is surrounded by banners, photos, and posters denouncing the government’s inaction against femicides.

The women who guard the anti-monument, where they sell some handicrafts, say that, for the moment, there have been no actions to remove the structure, but they have put up a sign that reads: “My children won’t eat goals. No to the World Cup.”

The anti-monument route began in April 2015 with the installation of the +43 memorial, dedicated to the 43 students from the Ayotzinapa teachers’ college and the thousands of people who have disappeared in Mexico.

Unlike traditional monuments, placed to commemorate past events, anti-monuments are a form of permanent protest and a demand for justice from the State in public space.

“The causes they refer to are not intended to be part of the past for remembrance or commemoration, but rather are events that continue to occur; at least, not until there is truth and justice for these grievances,” states the book “Antimonuments. Memory, Truth and Justice,” published by the Heinrich Böll Foundation.

In an interview with El Sol de México, Jorge Verástegui, coordinator of the foundation that has financed the construction of the anti-monuments, highlighted that the Head of Government has said that she respects the memorials placed in public spaces without the approval of the capital’s authorities, but has also warned that she can move them, which implies a latent threat on the eve of the World Cup.

“An attempt by the city government to ‘whitewash’ the city of social causes, protest, and resistance would be counterproductive,” predicts Verástegui, who warned that the groups are prepared to respond with marches, sit-ins, and road blockades if the anti-monuments are removed.

For a decade now, since the first of the 15 anti-monuments that make up the Memory Route was erected, the relationship between local governments and these structures has been uneasy and far from easy. While they have been tolerated, there have been attempts to move them to less visible locations, such as the Glorieta de las Mujeres (Women’s Roundabout).

“Of course the authorities don’t like anti-monuments, because they are a reminder of what they are not doing right,” said Meyatzin Velasco, Education Coordinator at the Miguel Agustín Pro Juárez Human Rights Center.

“It’s a thorn in the side of the various governments, in that they haven’t done their job of finding out where those responsible for the worst tragedies in the country are,” the activist added.

-

Veracruz: Oil Spill Victims Complain Of Insufficient Action by State Government

Residents of Pajapan, who live around Laguna Ostion, demand that the authorities take prompt intervention to solve the hydrocarbon spill in the southern part of the state of Veracruz.

-

San Luis Potosí Goodyear Workers Threatens Strike After Salary Increase Refusal

While Mexico’s general minimum wage has had a real increase of 116% in the last seven years, SITGM workers have received only 15.2% increases in the same period.

-

FIFA’s Cola Cup & Dystopian Horror

The World Cup’s arrival in Mexico is a stark illustration of the absurdity of the world we’ve reached thanks to the power of large corporations; of the crisis of our current civilization, a society trapped in a power economy, manipulated by addictions.