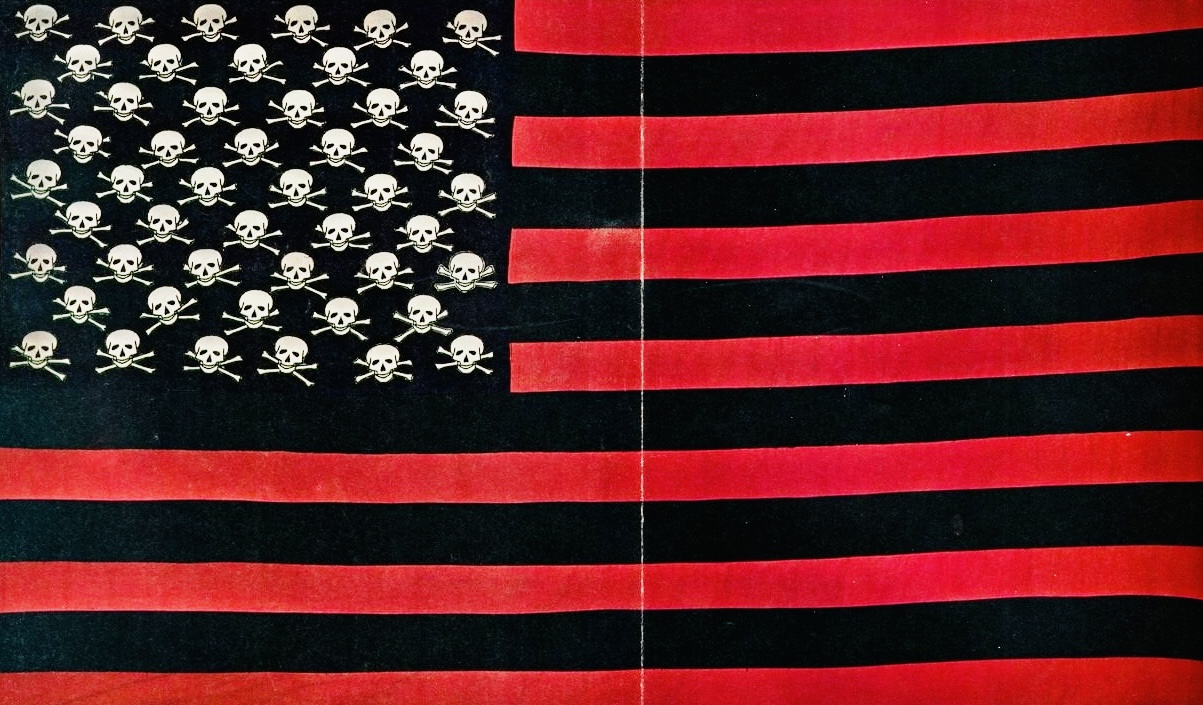

The Exhausted Empire

This editorial by José Romero originally appeared in the October 31, 2025 edition of La Jornada, Mexico’s premier left wing daily newspaper. The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Mexico Solidarity Media, or the Mexico Solidarity Project.

Since the Industrial Revolution, the world revolved around a center. England inaugurated the age of coal, steel, and the steam engine; its empire was the laboratory of modern capitalism. The wars of the 20th century exhausted that hegemony and transferred power to the United States, which emerged from World War II with half of global industrial production and an unprecedented privilege: issuing the currency that the rest of the world had to accept.

That “exorbitant privilege,” as De Gaulle called it, allowed Washington to finance its expansion with debt. Bretton Woods made the dollar the linchpin of the world economy, and when Nixon broke with gold in 1971, the system didn’t collapse: it was consolidated. Since then, much of the planet has worked, saved, and traded in dollars, financing the deficits and wars of the country that printed them.

The Cold War was the institutional framework for that power. While the planet was divided between capitalism and socialism, the United States used its industrial and military superiority to build alliances and markets under its influence. The fall of the USSR in 1991 seemed to confirm the definitive supremacy of the American model. But the unipolar world that emerged then expressed less its own strength than the exhaustion of competitors.

The neoliberal turn, championed by Reagan and Thatcher, restructured capitalism: financial capital displaced industrial capital; quarterly profitability replaced long-term investment; and labor-intensive production shifted to countries with low wages and weak regulations—first Mexico and Southeast Asia, then China. Following its accession to the WTO in 2001, China absorbed technology, knowledge, and capital under a state-designed framework: planning, public investment, technological control, and industrial discipline. Unlike other developing countries, it compelled foreign capital to partner with domestic capital, ensuring technology transfer and productive learning. The result is well-known: Chinese manufacturing far surpassed that of the United States, and in sectors like shipbuilding, it went from a marginal presence to nearly half of global production. In a generation, Asia—and China in particular—shifted the axis of the real economy.

Deindustrialization had strategic consequences. A power that outsources its manufacturing also erodes its military capacity. The US military industry faces cost overruns, delays, and difficulties replenishing inventories, and its advantage is shrinking in several technological frontiers—semiconductors, robotics, AI, telecommunications, and renewable energy. Russia is competing in hypersonic missiles and air defense; China is advancing in artificial intelligence and advanced manufacturing. The hegemony that was once a reality has become an increasingly difficult aspiration. We are witnessing the twilight of the long Anglo-Saxon cycle and the rise of a new equilibrium, with Asia as the economic, technological, and political axis.

Despite this, Washington acts as if the playing field hasn’t changed. It threatens rivals, sanctions allies, and imposes tariffs with Cold War logic. But each sanction accelerates the construction of alternative financial and trade circuits. The BRICS group—already larger than the G-7 in GDP by purchasing power parity—is expanding payments in local currencies and reducing its dependence on the dollar. Turning currency into a political weapon ends up eroding the very system that sustains it.

To the external situation is added the internal one. The United States is today a more unequal and fragmented society. One percent of the population concentrates a disproportionate share of the wealth, the middle class is shrinking, well-paying industrial jobs are disappearing, and the social mobility that once defined its national narrative is weakening. Politically, democracy shows structural wear: campaigns captured by corporate money, partisan polarization, and an aging Senate that blocks reforms. The institutional shell seems solid, but its capacity to adapt to the transformations of the 21st century is increasingly diminished.

The paradox is that this internal weakness coexists with a colossal external debt. By mid-2025, the United States’ gross external debt exceeds $28.6 trillion, equivalent to 94 percent of its GDP, while total public debt—internal and external—is around $38 trillion. It is an empire that no longer finances itself with its productivity, but with its credit: a country that lives off global savings and whose power depends on the world continuing to trust the dollar, even though more and more actors are beginning to look for alternatives

Added to this is the cost of maintaining more than 750 military bases in over 80 countries, an apparatus deployed to sustain an order that is crumbling. Each base is a reminder of a hegemony sustained by force rather than legitimacy. The United States can no longer bear the weight of its own imperial machine: it spends more on defense than the next 10 largest economies combined, abuses its power over allies and adversaries alike, and uses sanctions as a substitute for diplomacy. But this excess of dominance has begun to backfire. It no longer has the capacity to open new fronts: it is militarily tied down in Taiwan, Ukraine, Iran, and other tense regions, and yet it hints at intervening in Venezuela, an adventure it could not sustain without exceeding its economic and strategic limits. Every week it accumulates conflicts that exceed its actual strength, as if power had become an unstoppable inertia.

This disconnect between real power and moral narrative is what Professor John Mearsheimer of the University of Chicago sarcastically described when referring to the supposed meeting between Sergey Lavrov and Marco Rubio in Alaska: “It’s like a confrontation between Bambi and Godzilla.” He added that this “Bambi”—referring to the Florida senator—is causing a disaster in Venezuela solely out of electoral obsession, to appease the Cuban and Venezuelan expatriates in his state. The phrase, beyond its irony, encapsulates the strategic decline of the United States: foreign policy subordinated to domestic calculations, diplomacy replaced by media gestures, and a loss of touch with reality in the superpower that once dictated the world order.

The combination of chronic debt, military excess, inequality, and political paralysis constitutes a sustained deterioration. This is not a sudden collapse, but a cumulative process. The country that symbolized modernity faces limits that its financial and military power can no longer conceal. We are witnessing the end of Anglo-Saxon hegemony and the transition to a pluralistic world, where strength is measured not by the morality one preaches, but by the capacity to produce, innovate, and sustain one’s own order.

José Romero is Director of the Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas (CIDE). CIDE is a publicly-financed social sciences research center aiming to impact Mexico’s social, economic and political development.

-

CNTE Announces 72 Hour National Strike & March to Mexico City’s Zócalo

The class-conscious teachers union will also make “courtesy visits” to the embassies of countries who committed atrocities against Iran, to show their rejection of US imperialism.

-

Yet Another Mexican Citizen Dies in ICE Custody

The unidentified victim is the 9th Mexican citizen to have been killed in ICE detention since the beginning of 2025; this time in Adelanto, California.

-

Let’s Talk About Migration: Trumpist Persection

Millions of women who have endured unspeakable violence on their migration journey are now being persecuted in the United States by an extremely xenophobic and misogynistic government, led by Donald Trump,