The Fight for Water & Land

This editorial by Abraham Nuncio appeared in the July 10th, 2025 edition of La Jornada, Mexico’s premier leftist daily newspaper.

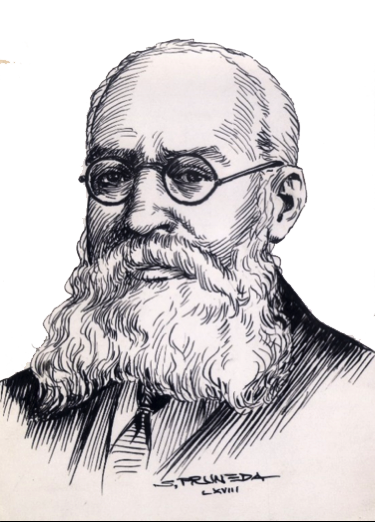

Andrés Molina Enríquez, our first sociologist, published his work The Great National Problems in 1909. He analyzed two of them, water and land, in relation to food, and the latter to agriculture. His loyalty to Díaz and the casuistic and specious nature of his work did not diminish its logic or intellectual honesty.

In its pages, one clearly perceives what liberalism was in Mexico and, therefore, the understanding of neoliberalism today. The injustice in land ownership and water distribution in the countryside and cities is explained by a well-known phenomenon: the concentration of wealth and power in an elite. He appropriately calls it monopolization.

The Lerdo Law of 1856 fractured the communal system of peasant social and economic organization through the dispossession that resulted from the liberalization of land tenure and the conversion of communal farmers into day laborers subject to landowners—mostly foreigners—who owned endless land. The use and abuse of land revived the colonial era, where, according to Wistano Luis Orozco (Legislation and Jurisprudence on Wasteland), cited by Molina Enríquez, “owner was synonymous with victor, and property was synonymous with violence.” Agriculture was oriented toward exports, thus undermining grain production and, consequently, food sufficiency, sovereignty, and social stability.

The sociologist explains that “expropriation and outrage are the barometer that increases and never diminishes the insatiable greed of some landowners: […] they take possession of either private land, or communal land, or communal land, and then with the most unheard-of shamelessness claim ownership, without presenting a legal title of acquisition, reason enough for the people in general to cry out for justice, protection, and shelter; but the courts, deaf to their cries and demands, are rewarded with scorn, persecution, and imprisonment, which is what is given to those who claim what is theirs.”

Today, a fifth of the national territory is under concession to mining owners. Just two, Bailleres and Larrea, account for 3 million hectares.

Agriculture could not be understood without water. The monopolization of the best lands was, at the same time, the so-called “irrigation districts.” And in the cities, the same thing happened in the countryside. Molina then pointed to “100 thirsty cities” where the shortage of drinking water affected, to a greater extent, the working classes and the most vulnerable sectors.

More than a century later, a revolution, two significant reforms—that of Cárdenas and that of López Obrador—and even the update of Molina Enríquez’s book by Samuel Schmidt with an identical title, the struggle for water and land continues to divide the interests of peasant communities, not a few of them indigenous, and those of the large beneficiaries of both assets, now considered national property.

A property whose real counterpart, according to the Constitution, loses its materiality and becomes untouchable and defendable private property over the general interest in episodes where the responsible institutions and the security forces at their service prove to be fierce guardians of corporate interests. In certain extreme cases, the rural guards of the past are now white guards, disguised as police officers with official badges and even the military uniform of the Mexican Army.

The individual is the synthesis of the social relations of production—as Marx saw it—and one can call, for example, Renato Romero Camacho, a man whose condition is poverty and whose character is that of an irreducible social fighter in defense of access to water for the peasant communities of Puebla. He has been harassed, threatened with death, beaten, imprisoned, and arbitrarily prosecuted for alleged damages to the company Concesiones Integrales, one of those favored by Agua de Puebla para Todos (“a business model,” its advertisement says). The Morena government of Puebla claims to govern for everyone, and the Federal government does the same. And it’s true: its substantial concerns concentrate power and wealth in one percent of the population, leaving whatever’s left for the remaining 99 percent. The difference is not noticeable in the speech and the photo.

This harassment, arrogance, arbitrary actions, and aggression by the authorities, in collusion with local and transnational companies, are suffered daily by the Chiapas communities organized in the EZLN, those in Oaxaca, the State of Mexico, Nuevo León, San Luis Potosí, Jalisco, La Laguna, and most states and regions of the country.

After Salinas’s agrarian counter-reform, something similar occurred to what happened with the Lerdo Law: the concentration of the best lands in the hands of a few families, the conversion of ejidatarios into day laborers subject to the new latifundists, the expulsion of 15 million peasants, and the Porfirian-inspired agricultural reorientation, with the same effects: weakening food and political sovereignty and social instability.

There has also been an ignominious addition: the enormous mining concessions. Today, a fifth of the national territory is under concession to mining owners. Just two of them (Bailleres and Larrea) account for 3 million hectares. In 70 years, and until Salinas’s reform of the mining law, the concessioned hectares totaled less than 13,000. That reform considered mining to be a property “superior to any other,” even to the point of obtaining expropriation by the concessionaire (La Jornada, 4/6/15).

No one should be surprised if the impunity of the mine owners rhymes with extraterritoriality.

-

People’s Mañanera February 9

President Sheinbaum’s daily press conference, with comments on scholarships, return of mining concessions, PRIAN exposed, Bad Bunny Super Bowl, and aid to Cuba.

-

8 Million App Users, TV Soap Opera Ad… & the PAN Still Can’t Find New Members

In Mexico, where political parties are currently publicly financed, the right wing PAN has spent a staggering amount during its lackluster recruitment drive.

-

Mexico’s National Film Archives Workers Demand Dignity

“Our struggle is legitimate; we are not asking for privileges or luxuries, only better working conditions and job security. We also seek dialogue. This situation has become unsustainable.”