Unity! The Filipino-Mexicano Grape Strike

Everyone in the labor movement and beyond has heard the cry, “Si, se puede!” (“Yes, we can!”), first uttered by Dolores Huerta of the United Farm Workers (UFW) in 1972. The names of Huerta and César Chávez, the UFW’s first president, are known everywhere in progressive households — probably in yours, right?

You’ve probably also heard the phrase, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” But do you know who said it first? It was Larry Itliong, a Filipino farm labor organizer instrumental in forming the UFW, and its founding vice-president. But few of us know Itliong’s name or the critical role he and the Filipino workers played in the historic Delano, California, grape strike.

Lorraine Agtang wants to change that. In fact, she says we must retell the story and put Filipino workers back into the picture. She recounted that building alliances across race, ethnicity, language and culture was hard; organizing Mexican and Filipino workers required different approaches, and the two groups held negative attitudes toward each other — fostered by the growers — and these attitudes had to be overcome.

But they did it, and it is that unity that is the main lesson of the Delano grape strike. Because if Mexicans and Filipinos hadn’t joined forces, our labor history would be far different: the grape strike broken, workers defeated, the UFW not born. And you and I would have been poisoned by eating grapes contaminated by pesticides and watered by the blood and sweat of immigrant workers.

Lorraine Agtang is one of the few surviving Filipino grape strikers who kicked off the militant farmworker movement in 1965. She has dedicated her life to the struggles of farmworkers: organizing for the UFW, managing Agbayani Village for Filipino elders, and running programs for the children of farmworkers and community members. She still loves instilling pride in young people about the workers’ movement — especially the Filipinos’ contributions — that opened the door to the opportunities they enjoy today.

Back in the 60s, while still a child, you worked in the vineyards in Delano, California. What was life like for you?

We picked grapes in the fields with our parents to help support the family because no laws prohibited children from working in the fields at that time. In 1965, when I was 13, the Delano grape strike started on September 8. My first exposure to civil disobedience. It was scary!

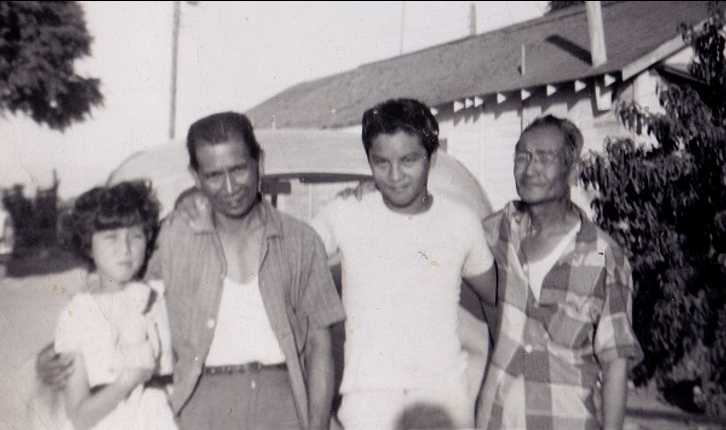

My father was Filipino, and my mother was Mexican. They met in southern Texas while working in the fields, and my father learned Spanish so he could communicate with my mother, who didn’t speak English. They married, moved to and settled in Delano, picking grapes. I and four of my siblings were born in the labor camp. The local doctor didn’t arrive until our heads popped out; that’s what happens to poor families without medical insurance.

My father was Filipino, and my mother was Mexican. They met in southern Texas while working in the fields, and my father learned Spanish so he could communicate with my mother, who didn’t speak English. They married, moved to and settled in Delano, picking grapes. I and four of my siblings were born in the labor camp. The local doctor didn’t arrive until our heads popped out; that’s what happens to poor families without medical insurance.

Delano was split by railroad tracks. The whites lived on the east side, and the Mexicans and Filipinos on the west side. But our camp was on the east side, a half-mile out, so I went to school with the white kids. One Sunday in church, the priest spoke about how Catholics should be responsible for the poor. His message was meant for the growers — but I thought he was talking to me! I took it to heart, helping the poor became my life’s mission.

I married early and had three kids by the time I was 18. You couldn’t go to school if you were pregnant back then, so I only finished 8th grade.

When did Filipinos arrive in the US and begin working as farm laborers? Did they work alongside Mexican migrants?

My father was in the first wave of migrants coming to the US between 1920 and 1940. Many joined the military, but most became field laborers living in barrack-style housing on the grower’s land. They worked in a crew of up to 50, with a foreman in charge. The growers kept the Mexican and Filipino workers separated into different crews so they could be pitted against each other. They’d say, “The Mexicans pick more than you!”

Filipino farm workers were the first to go on strike. Way down in Southern California, in Coachella, it gets very hot, up to 115 degrees. Because of the heat, the grapes rot quickly, and there were only 4 weeks to pick them. The Filipinos asked for a raise, and — because of the time crunch — the growers agreed.

So, the idea moved to Delano. But there, the workforce was huge, and the growers refused to raise wages. The Filipinos formed the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC). Its leaders were Larry Itliong, Pete Velasco, Philip Vera Cruz, and Andy Imutan. Itliong wasn’t a worker himself; he was a labor contractor who got Filipino workers hired at specific farms. Foremen and community people also joined the workers because, no matter their position, they identified with the situation of their fellow Filipinos.

On September 8, 1965, AWOC’s 2000 members walked out of the fields, and the historic Delano Grape Strike began!

AWOC leaders knew they couldn’t win the strike; many Mexicans crossed the picket lines. They went to César Chávez, who had founded the National Farm Workers Association, and asked him to join the strike. César asked the members to join, but some Mexican workers said no. So César said, “OK, I’ll quit, and I will join the Filipinos.” Quickly, the members changed their minds.

When the Filipinos and Mexicans joined together, it was a healing moment for me personally — Filipinos didn’t think I was Filipino enough, and Mexicans didn’t think I was Mexican enough! But that unity was also crucial to the strike, and that’s how the United Farm Workers union was born. In 1966, the Filipino and Mexican organizations merged. César Chávez was president; Larry Itliong was vice president; Philip Vera Cruz and Dolores Huerta were board members.

After five years of the strike, protest marches, demonstrations in Sacramento and the national grape boycott, the first agricultural workers contract was finally signed in 1970.

Was life particularly hard for the older generation of Filipino workers?

We call them “manongs,” or “older brothers.” The manongs had no families. At the time, anti-miscegenation laws prevented Filipinos from marrying white women, and no single Filipina women lived in the area, except prostitutes. The manongs lived in shacks in the camps in miserable conditions; some didn’t speak English and didn’t know how to use a bank. Then, after the strike started in 1965, the growers kicked the manongs out of the camps. Regardless, the manongs were on the picket lines every day, forming the backbone of the strike.

But in 1973, after the boycott ended, the United Farm Workers built the Agbayani Retirement Village to give the manongs a comfortable home for their final years. Many volunteers from all over California came to help build the village, including farmworkers and Filipino college students who came on weekends and in the summer, and it was an education for those young folks! Hearing the stories, many had tears in their eyes, and many later became advocates. For example, they won the addition of Filipino history to the state high school curriculum.

Agbayani had 62 units, a community dining room, a Filipino cook, a vegetable garden and a nearby clinic. Other residents became family in this safe and beautiful place. I was the manager of Agbayani for the first year after it opened. But then, in 1976, I became a union organizer.

All the Manongs have died now, and Agbayani Village is a National Park Historical landmark. We’ll have a big 50th anniversary celebration there on October 19, 2024.

What an amazing life you’ve had! What are the lessons you leave with the farmworker kids in the youth programs you ran for 30 years?

The importance of worker unity. If the Filipinos and Mexican workers hadn’t joined together, they wouldn’t have won. I want Filipino students, male and female, to know the crucial role Filipinos played in the movement and in the creation of the UFW. While César is well known as its founder, the Filipinos who were also founders have often been forgotten. Their stories must be included, or the significance of the Mexican-Filipino alliance will be lost.

For me personally, the union gave me tenacity: you can demand what you want and need, you can’t give up. As a Hispanic Filipina woman, I learned from César that you are equal to anyone. Never feel like you are lesser.