Was There A Regime Change After 2018?

This article by Carlos San Juan Victoria originally appeared in the December 2025 edition of Memoria: Revista de Crítica Militante. We thank Memoria for permission to reprint the article and encourage you to support Memoria and the Center for Studies of the Labor and Socialist Movement. The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Mexico Solidarity Media or the Mexico Solidarity Project.

The Confrontation Between Narratives & the Understanding of Historical Processes

The closing of our diploma course on the transformations in the history of Mexico coincides with a bitter dispute over the narratives of what happened in our country since the 2018 presidential elections, its present and its imminent future.

Perhaps reductively, I distinguish two narratives: a) the one that insists that a period of destruction of democratic institutions, of economic decline and of increasing disorder in social life is beginning, which now points to a change of authoritarian or dictatorial regime; and b) the one that argues that the so-called 4T has already placed us in a post-capitalist phase where neoliberalism is being dismantled, sometimes almost by decree.

The first of these narratives is heavily influenced by its notion of regime, sometimes restricted to the rules of electoral competition, and at other times to the more prolonged reforms of the institutional fabric, which are reductively placed at the beginning of the “democratic transition.”1 But very little consideration is given to what, in history, constitutes a regime change—that is, a change in the polis, in the political community, where the state and the life of society change.

That was what happened with the conquests of three parts of the world by the expansive West, whose last chapter was the “universal” model of coexistence after the fall of the USSR, and its new gospel of democracy reduced to electoral rules, free markets, extreme individualization and minimal states.

Both narratives share the idea of the destruction or creation of a political order in the Jacobin tradition of a coup, a rupture of the status quo from which something new and already formed emerges. But in history, that doesn’t happen.

What is recorded are regime changes as very conflictive and prolonged processes, because, to give an example of what we are experiencing today, the forces that prospered during 6 six-year terms, the neoliberal period, are still dominant in business, financial, cultural and media life.

Mexico is integrated as a prosperous exporting economy with the US, and private investment represents 90% of the country’s total investment, according to figures from Plan México. Private press, radio, and television are dominant and daily prescribe the neoliberal creed to millions of people, telling them that there is no other way out than to return to “democracy.”

Neoliberalism itself was established as a firm new order during three presidential terms (de la Madrid, Salinas, and Zedillo) and, already showing serious cracks and decay, has continued for another three. The Mexican Revolution only began to name itself ten years after it occurred, and its regime change was finally consolidated under Cardenismo.

How to Distinguish Regime Change Between an Order That is Still Consistent & a New, Uncertain Direction?

The Fourth Transformation (4T) arrives with a discourse rooted in a long historical process, which simultaneously fosters the belief that transformations will be achieved within a single six-year term. At best, AMLO, like Miguel de la Madrid before him, redirects the country’s course, and, in part like Salinas, lays the groundwork for prolonged processes of change. However, he must coexist with a large coalition of still-existing and, to some extent, interconnected powers. Change must occur within the most consolidated and hegemonic neoliberal order in Latin America. We are engaged in a “war of position,” as Gramsci termed the struggles for hegemony, the cultural leadership needed to construct alternative systems to the existing ones.

But it now holds in its hands the principal instrument of the transformations experienced from the Porfiriato to the present day: the State, understood not only as a legal framework with its own fiscal resources, the already territorialized force of the army and the national guard, the capacity to reform institutions, and, above all, popular support. In Mexico, the strong State of the Revolution achieved its full sovereignty when it changed its relationship with society and prioritized the majority of the population; it boasts a long tradition of struggles by the political, social, and cultural left that have fought for social justice, inclusive development, and full sovereignty.

The forces that prospered during the six presidencies of the neoliberal period are still dominant in business, financial, cultural and media life.

From 2015 to the present, the “political center” that sustained neoliberalism under a democratic guise has been overwhelmed by populations fed up with being excluded from the economic boom and bearing the costs of austerity, deindustrialization, and poverty generated by unipolar globalization. Voters have deserted the “center.”

Mexico and the progressive movements of Latin America were the exception to the left in a massive shift in the West toward right-wing nationalism. In the current era of rising multipolarity, Mexico has arrived at the forefront of the struggle for a sovereign state that negotiates its engagements with the world based on national interests.

Therefore, beyond the dominant narratives, we are facing a process that is actually a battlefield where the main issues are: a) whether there is a direction for the transformations or not, b) whether or not the strategic areas exist to achieve regime change; c) whether, in the heat of the battlegrounds, there are significant signs of halting and changing the tendencies inherent in neoliberalism, and whether new possibilities are opened up; d) whether it is possible to politically, peacefully, and legally neutralize the opposing forces that now coincide within the country and abroad with Trumpism in the USA, and increase sovereign power in its alliance with the popular majorities, where regime change, for or against, occurs within a democratic framework and not through open destabilization.

Strategic Areas for Guiding Regime Change

I suggest that for your own reflection you question not the narratives, but the historical process lived, to determine if in these seven years another guideline for the national course has been defined and in what strategic areas this occurs in its dual dimension, as a brake on systemic inertia and at the same time placing another course, the rails, for the daily struggle for a change of regime in the medium term.

I present my exercise.

The possibility of restoring full sovereignty, recognized outside and within its borders. Mexico was one of the best students to learn, contribute and apply the neoliberal gospel of markets as rulers of economic and social life, minimal democracy, extreme individualization and States limited in their sovereignty.

Taking a different path means innovating within Mexico’s historical formula of a strong state to create a new order for social life as a whole. Externally, this means being recognized as an equal among equals, with respect. Internally, it means acting as a power that coordinates, guides, and limits social, territorial, and corporate powers, adhering to the individual and social guarantees of the Constitution. Neoliberalism failed in both of these tasks. It left behind a vassal state, fragmented and with unchecked internal powers. I don’t believe the current administration has yet resolved these deep-rooted problems, but there are signs of significant change worth considering.

Only now the strong State has to innovate in an expansive democracy, with comprehensive rights, participatory and recognizing diversity, which nevertheless coincides in the great struggles for justice, equality and freedom of individuals with ethical ties and responsible for contributing to life in the political community.

The creation of a political majority. If we observe the political process experienced in these 7 years, there is the constant construction of an electoral majority that unfolds in the conquest of the Executive, Machiavelli’s modern prince, in growing blocs of governors and municipal presidents, as well as in majorities in the legislative power and the reform of the judicial power.

Thus, the Fourth Transformation (4T) is the largest and best experience of Latin American progressivism in its more than 25 years of existence. With a President who navigates the Trumpian offensive with approval ratings of 70 to 80%, it could be said that the main task of sovereign reconstruction is progressing, within the political rules of electoral competition and respecting the constitutional guarantees of citizens’ rights to free expression and assembly.

And to achieve this, as happens in any power struggle, concessions have had to be made on very difficult issues such as migration, but progress has been made in acts of sovereignty such as the package of reforms that reorient the economy, democracy and justice, still uncertainly and with errors and omissions, but already in another direction.

Strengthening the popular and middle-class majorities. I’m referring to the difficult task of rebuilding environments of income, comprehensive rights, greater representation of their interests in party and government agendas, with constant accountability and the expansion of recall elections. What stands out here is the halt to the neoliberal trend that was eroding these environments and the enormous gap created between parties, governments, and the popular majorities. Popular politics had disappeared from the scene. Now, politics can depend on its performance to deliver for its constituents, with the inevitable setbacks.

Seizing this moment to consolidate productive nations in the reorganization of the world. The world’s leading powers—the USA, China, Russia, Germany, and India—know that the present and immediate future belong to nations that strengthen themselves as productive entities, where investments are directed not toward financial speculation but toward real production. And where the dignity of workers can be restored, along with their well-being and education, to increase productivity. This is an opportune moment for various forms of coordination and promotion of productive enterprises and for strengthening the world of work. The formula and policies implemented since AMLO’s administration, and now embodied in Plan México, aim to capitalize on Mexico’s “Chinese moment,” when it grew as an exporting powerhouse in exchange, crucially, for foreign corporations partnering with national entrepreneurs and gaining access to technology. Now that the USA is building up its borders with nearshoring to avoid dependence on the “factory of the world” that is China, and even as an unexpected effect of tariffs that make it difficult for other countries like India to access the large US market, there is a national opportunity to consolidate itself as a prominent productive force.

Exercising sovereignty to regulate dependence on the US market and to ensure corporate social responsibility. Moving from unregulated capitalism, devoid of social and environmental responsibility, speculative economies, and a lack of adherence to a national plan and interest, to what AMLO’s “moral economy” envisioned: compliance with regulations, curbs on extractivism, and dispossession. The Mexico Plan is the implementation of these guidelines in a medium-term plan. What remains to be seen is whether it is also capable of implementing precise regulations that prevent a return to unfettered capitalism, and above all, whether in the medium term it will be geared towards diversifying its export platform towards multipolarity and the BRICS markets.

Reversing the trends toward social decay. Among the serious shortcomings of neoliberalism is that it concentrated attention and resources on building an export platform, but neglected and deteriorated security, health, education, and housing, among other components of well-being, in the country’s regions, most notably those outside the USMCA.

Since AMLO, the trend has been towards restoring the sovereign state as a producer of high-quality, widely available public goods, but the network of loopholes created by privatizations in these areas, and therefore, the state’s withdrawal not only from public goods but also from its role as a legal and public security force in the country’s regions, the proliferation of associations between the illegal and the legal, between criminal networks, police and military, companies and banks, and political classes, points towards a breakdown of regional societies and the fracturing of sovereign power.

Much of this persists, and even permeates Morena’s broad coalitions. It’s a treacherous terrain where every step forward risks a misstep. But the continuity of measures stands out, for example, in security and health, where, despite setbacks, there is continuity between the territorial deployment of infrastructure and trained personnel, and the current open struggle for control of territories held by social powers and criminal political fiefdoms, or the incremental progress in the public health system that halted privatizations.

The Two Orientations of a Regime Change in the Second Six Year Term of the Fourth Transformation

The peculiarity of trying to advance progressive change when the power coalitions aligned with neoliberalism and the border with the Empire are in good health but lack popular and state support makes it possible, beyond the conflicting discourses, that there are actually two possibilities for regime change: one, already out of step with the historical time of the rising multipolar world, which is restorative of unipolar Neoliberalism, and another that strives for a historical form of capitalism with power correlations in favor of the popular majorities and with tendencies towards greater socialization of life and public goods.

The serious crisis facing the opposition and the formerly hegemonic “center” now finds a powerful ally in Trump’s United States and its attempt to subjugate the sovereign nation project, reviving the idea of confronting and defeating the Fourth Transformation (4T). Every act of aggression or threat is celebrated, fueling the desire or imagination to see the judicial reform canceled, or for military intervention by powerful neighbors who, far from wanting to be involved in another open war, are keen on constant destabilization through various mechanisms.

But the truth is that the federal electoral calendar (2027-2030) is reviving their spirits, and they are already proposing to form center-right coalitions to “restore democracy” or to found new parties sympathetic to Trumpist nationalism, such as the nascent Republican Mexico party, with close ties to Ricardo Salinas Pliego. And there, the US pressure on the 4T (Fourth Transformation) is a powerful fuel for their ambitions. One of their major problems is that both the center-right and the unipolar nationalist right lack connections with the majority of voters.

The other direction for regime change is to consolidate the electoral majority and utilize the republican mechanisms of the three branches of government to effectively advance in the strategic areas we discussed. Its main challenge is to navigate and neutralize the emerging climate of destabilization. However, while this was utopian in 2018, it is now a real possibility, and we will see if it materializes in the long process of achieving a true regime change as a political community, as a society, and as a state.

- Editor’s note: A term given to the period of the decline of the power of Mexico’s PRI party, beginning in 1977 with political reforms and culminating in the election of the right wing PAN President Vicente Fox in 2000. This was also primarily the period in which neoliberalism took hold of the Mexican state and economy. ↩︎

-

Workers Party Claims Sheinbaum Electoral Reform Will Eliminate Party System

The socialist party’s leader recalled the democratic spaces that the left managed to conquer with the 1977 & 1996 reforms, a “fruit of countless struggles, repressions, imprisonments, disappearances and even armed uprisings.”

-

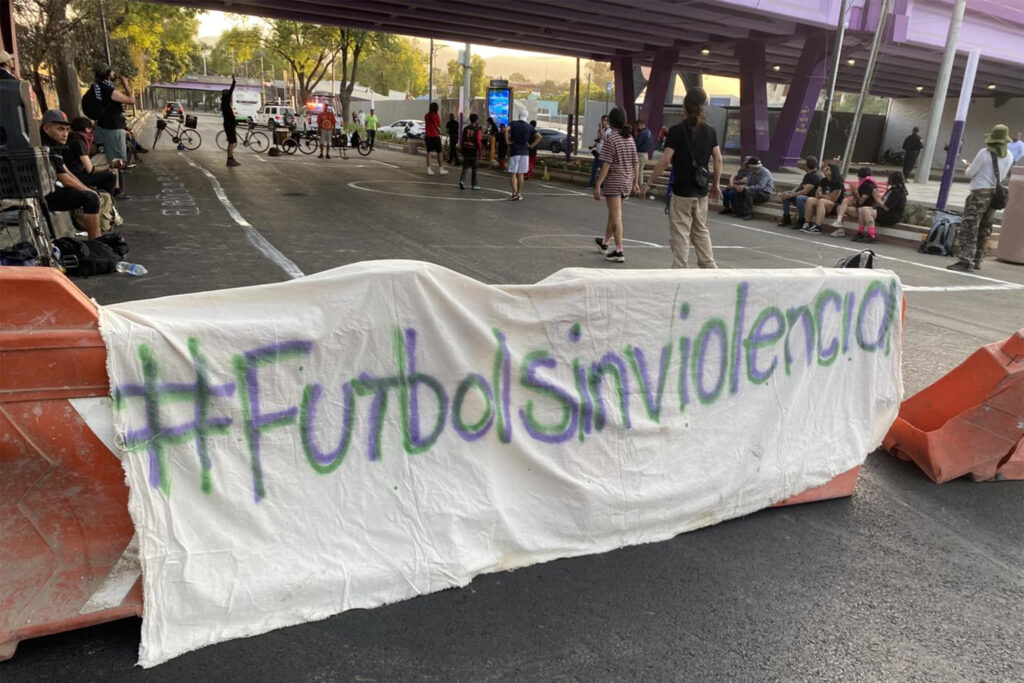

Anti-FIFA Challenge: Football Defends the Territory

Mexico City residents are organizing Anti-World Cup Days to protest water theft and gentrification that have accompanied preparations for the World Cup, put on by the corrupt, international criminal consortium known as FIFA.

-

Tridonex Strike in Matamoros to Start March 6th

1,300 workers are expected to strike, demanding the company fulfill its obligation to pay workers in full. Tridonex is owned by First Brands, the US autoparts corporation accused of massive fraud.