When Work Becomes a Crime

Under current US policy, an estimated third of workers from other countries working in the US are deemed “criminals” and therefore subject to arrest, indeterminate detention and deportation. How did we get to this point?

The US was founded by European nationals who migrated voluntarily. They settled in North America, killing or forcibly driving off the Indigenous populations to get what they needed — land. To work that land, they turned to Africa and shipped back people in chains, designating them legally as “chattel,” not humans. Later, on the west coast, sea captains turned to China for cheap, unfree and expendable labor. The Chinese were “shanghai’d,” or kidnapped — men as unwilling sailors and women as prostitutes.

Besides enslavement and forced labor, labor shortages have often been remedied by bringing in temporary workers from other countries. That’s the idea favored by both Democrats and Republicans. They assure us that temporary contracted workers are the only “good” migrants and that expansion of the temporary guest worker program is the only way to bring in the foreign workers US businesses need.

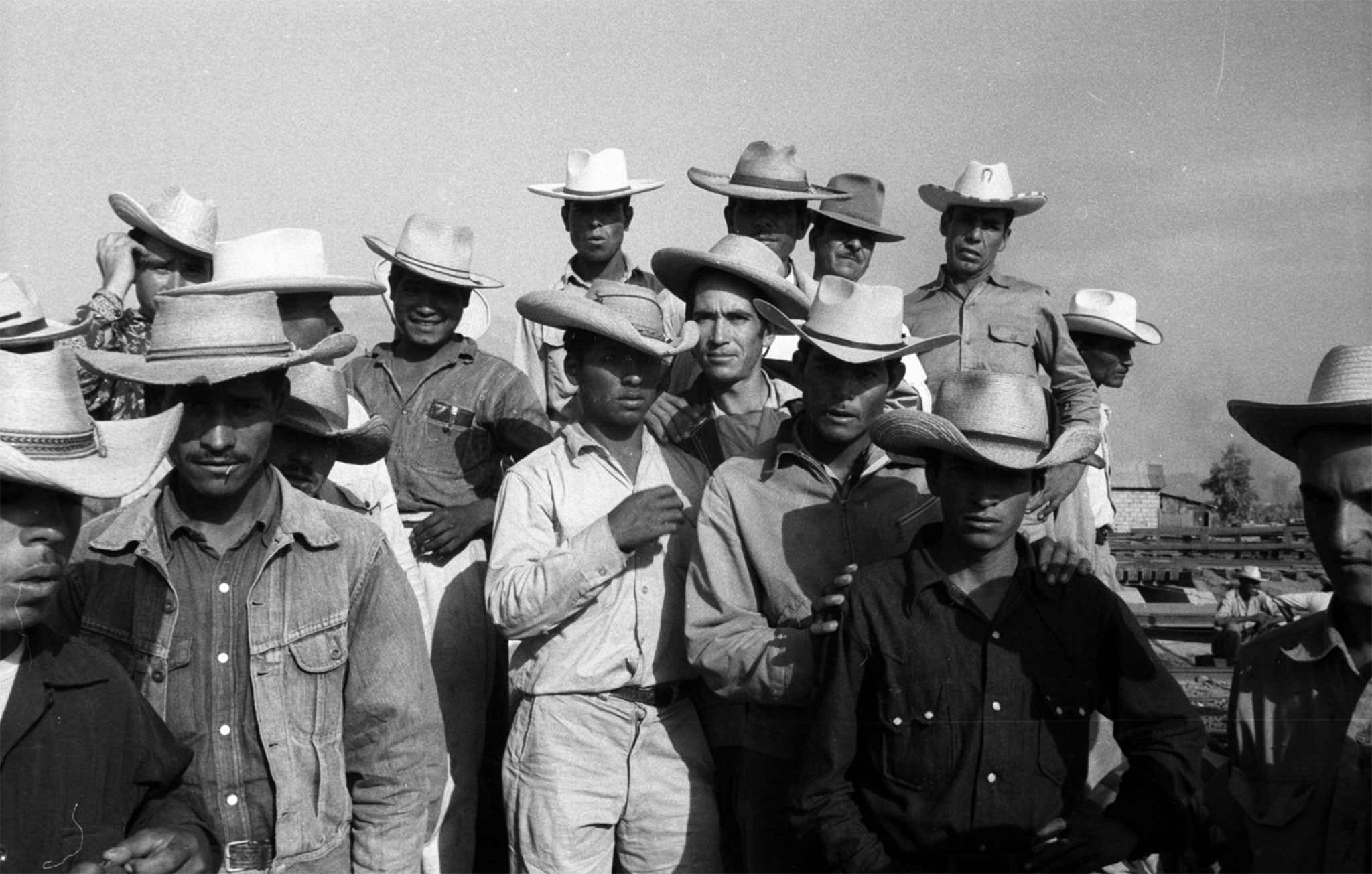

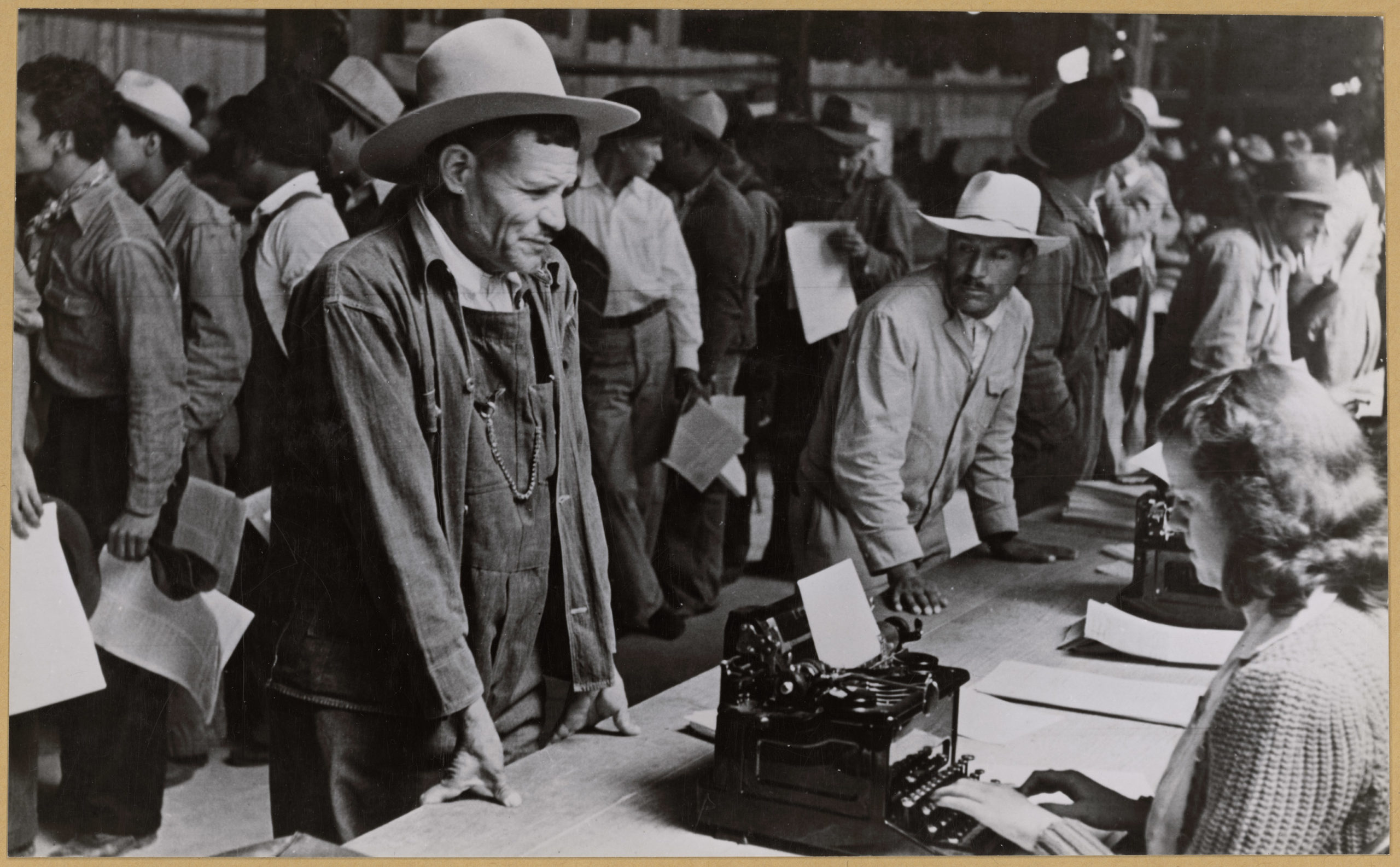

To become a contract worker, some recruiters in Mexico hired by US growers ask applicants to show their hands. If rough and calloused, it means they make a good candidate. Recruiters act like modern day slavers, who examined the bodies of Africans, concerned with nothing more than their physical capacity to do back breaking work.

So who does that leave as “illegal”? Only the people who come voluntarily, as the original settlers did — but who don’t have their main criteria for legality: whiteness.

Today, Trump’s fat magic marker draws a harsh line between those with papers and those without. Working without a permit has become a serious crime, with horrific punishments such as being disappeared into El Salvador’s concentration camps.

As we search for better immigration policies, Maria Quintana’s research should make us all shift our focus. The frame of “legalization” doesn’t deal with the reality of the US’s need for more workers or with the lack of workers’ rights for both undocumented and temporary workers. How about using a human rights frame, honoring the humanity of all workers, whether US or foreign-born, temporary or permanent?

The detaining and deporting of immigrant workers from Mexico and Central America has raised alarm in all of us. We are republishing our May 31, 2023 interview with Dr. Maria Quintana, who discusses how making migration a question of legality evolved and how it has put all migrant workers at risk.

Maria L. Quintana, an Assistant Professor in Sacramento State University’s history department, teaches courses that cover topics ranging from race, empire, and civil rights to labor, immigration, and Latinx history. Her book, Contracting Freedom: Race, Empire, and U.S. Guestworker Programs, was published in 2022.

Do you have a personal connection to the story of “guest workers” in the United States?

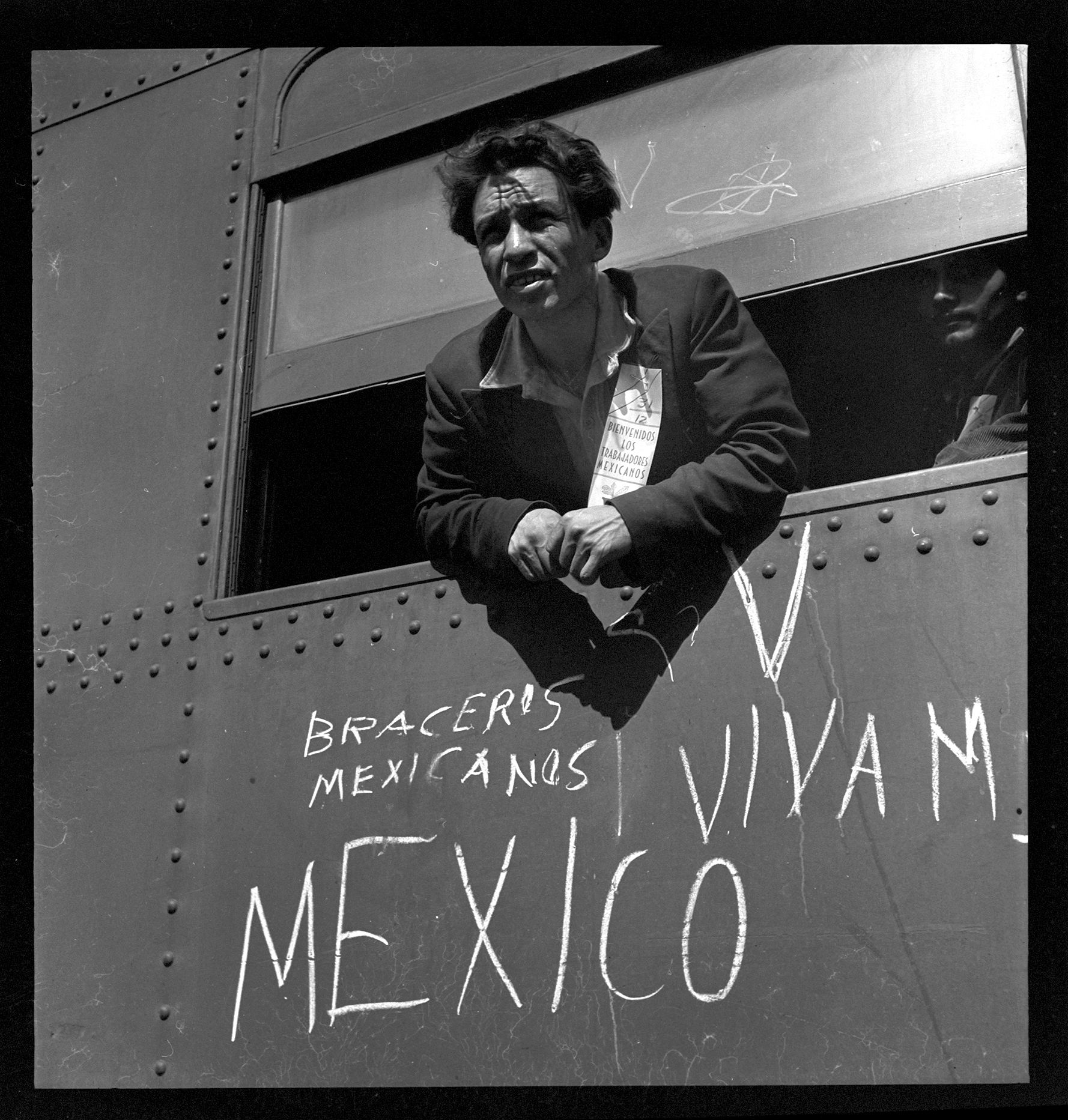

My great uncle worked as a bracero, and I grew up in a neighborhood called la colonia, a former orange orchard that hired braceros. My family’s and my people’s history as the working backbone of California interested me, and I wanted to find out more about the colonial roots of the Bracero Program.

How did the idea of temporary work — based on a labor contract between an individual worker and employer — take hold in the US?

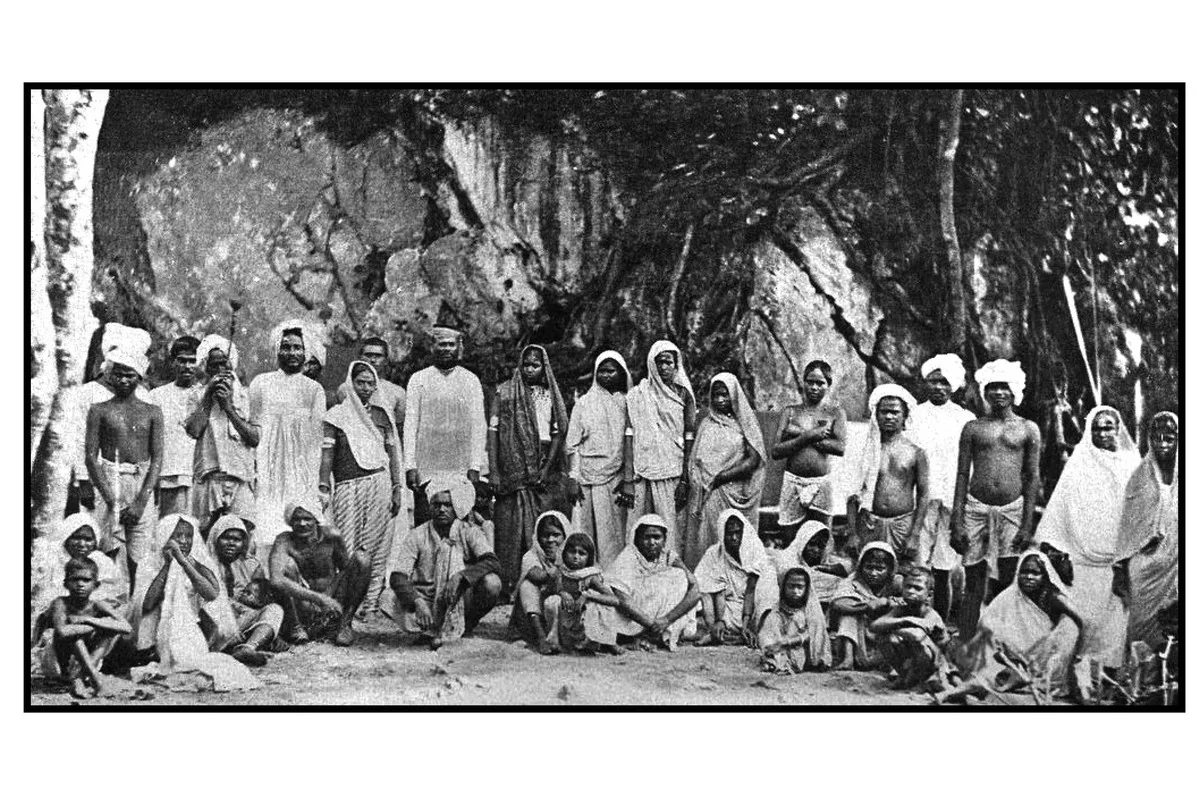

This idea originated in England. With slavery about to be ended in the early 1800s, slave owners in the British West Indies wondered who was going to be doing the work once they had no slaves. How could they get docile workers that they could control?

Their answer — a system that described workers as “free” with contractual rights and paychecks — offered a solution that skirted the arguments against slavery. Plantation owners started to import workers from India to the British West Indies on this basis.

In the United States, with the mass importation of Chinese after slavery’s abolition, some protested that “coolie labor” amounted to “slave labor.” This sentiment led to the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Acts, as well as the 1885 Foran Act, legislation that prohibited imported foreign labor.

But the Foran Act had a loophole that allowed Mexican workers with temporary contracts into the United States, and employers used this loophole in 1917, before US entry into World War I. But the program proved short-lived. The Mexican government ended it in 1921, in part due to the exploitation of workers that the loophole made possible.

At that time, with little border enforcement, travel between the US and Mexico for seasonal work remained pretty fluid. But contracted labor became popular again after the 1930s as the success of the New Deal changed the concept of the state. People began to see the government as a benevolent force that could protect workers.

By 1942, a new consensus had emerged, shared by conservatives and liberals. They agreed that importing foreign workers who could freely enter into legal contracts determining the terms of their employment would bring mutual benefits to both worker and employer.

Unions as well as employers supported this idea of contract labor. Legendary farm worker organizer Ernesto Galarza, for instance, felt that a labor arrangement modeled on Depression-era resettlement programs — efforts that provided internal US Dust Bowl migrants with housing and new skills — could benefit Mexicans as well.

These workers could learn new skills and take those skills back to México. So the Bracero Program originally faced little opposition.

The Bracero Program emphasized a worker’s freedom to accept a contract. Why do you say that guest worker programs actually served to legitimize US imperialism?

Contracts for temporary labor coerce. They tie a worker to a single employer, with no supervision of the contract to guarantee a basic standard of living.

Labor contracts also expand state power over immigrant workers. In effect, the “legality” of these contracts produces the problem of “illegality.” You cannot be “illegal” without a “legal status” for comparison. The US Border Patrol in 1924 began as a program too small to have any effect. But after 1942 — and the start of the Bracero Program — the Border Patrol’s numbers increased twenty-fold!

Also in 1942, after Pearl Harbor, the government put the Japanese in the US, many of them agricultural workers, into concentration camps. Officials essentially co-constituted Japanese internment and the Bracero programs after multiple hearings that considered both populations and how to treat them. Living conditions for both were similar.

An “empire” has complete state control over its population. In the United States, workers categorized as “foreign” became subject to US imperial rule. Workers did resist, with work stoppages and ripping up and breaking contracts by leaving their contractual employer. But their moves to escape their contracts broke the law. “Legality” increased oppression.

Did the growing civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s impact the braceros?

Ernesto Galarza, appalled at the actuality of the Bracero Program, spent the rest of his life fighting bracero mistreatment. The National Farm Labor Union — the NFLU — that Galarza led tried to organize braceros with domestic farmworkers, but the growers could just fire “troublemakers” and replace them with either contract or undocumented workers.

Immigrant workers came to be seen as a problem, a group that undercut efforts to organize and protect domestic/citizen workers.

Even among union organizers, the division became not just a conflict between workers and bosses, but also between domestic and migrant labor. The question in my research became, “Civil rights for whom?” The struggle for civil rights left out guest workers.

How and why did the bracero program end, and what has happened since then?

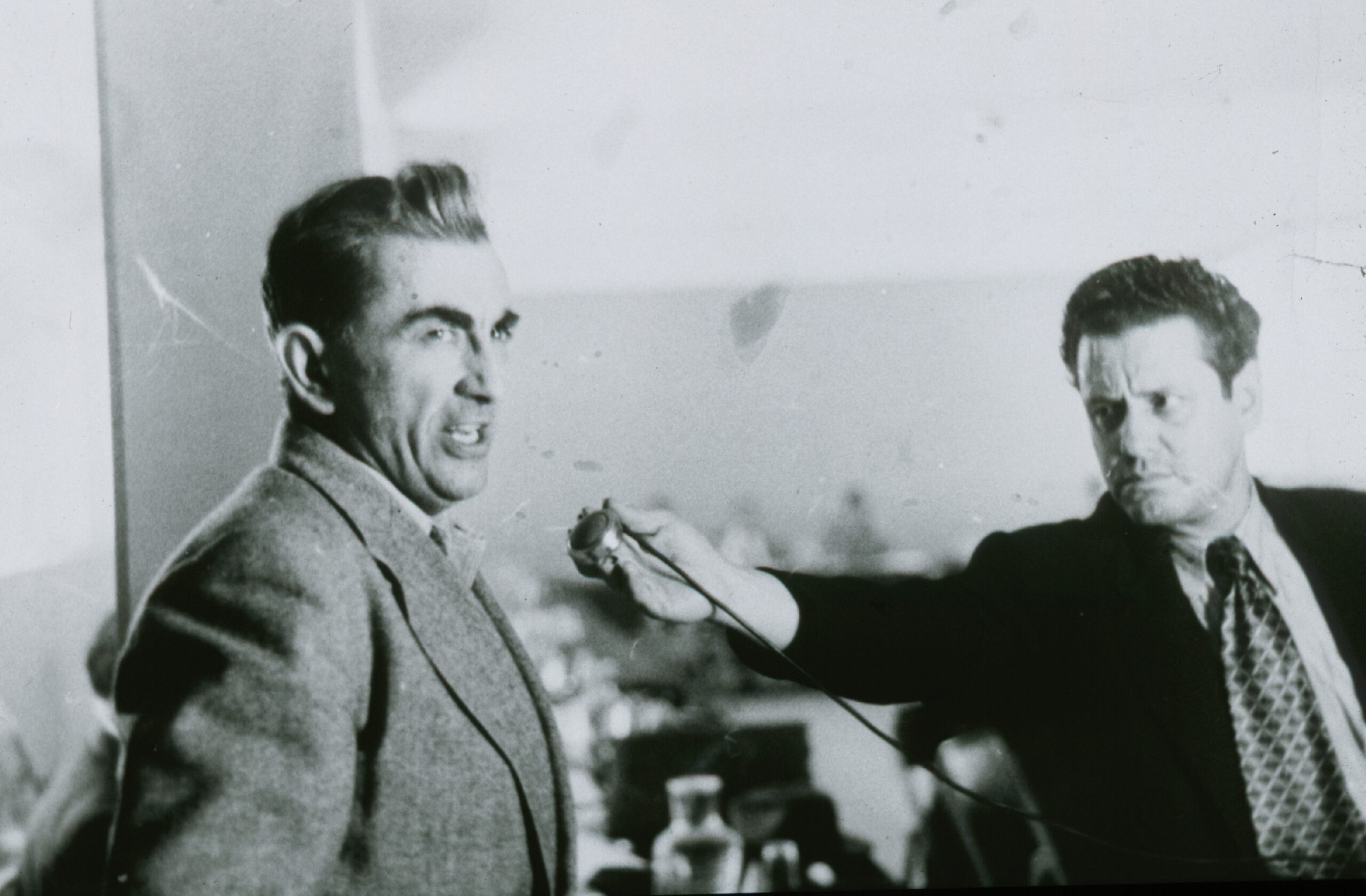

The United Farmworkers finally brought national attention to the reality of the conditions braceros labored under, and the 1960 network television documentary Harvest of Shame reached a wide audience. The Bracero Program ended in 1964, with, once again, the debate around that move stressing the need to protect domestic workers.

In 1986, to deal with the problem of predominantly Mexican undocumented workers, the Immigration Reform and Control Act — the IRCA — became law. This legislation traded off granting some immigrants a path to citizenship with making other immigrants even more vulnerable to deportation.

Since then, with the continued liberal consensus on the issue as “legalization,” that trade-off has been part of every major immigration reform proposal.

The new H2-A rules on the “Temporary Agricultural Employment of Foreign Workers” allow more workers to come into the US with individual contracts that tie them irrevocably to individual growers and make them vulnerable to corrupt recruiters in México.

These rules subject agricultural laborers without papers to the growing militarization of immigration control. We’ll see deportations — already at all-time highs — increase even more, since legalization requires an expansion of state power to enforce the law. Contract labor remains bad for both new guest workers and undocumented laborers already working.

What can we do?

We must defend all farmworkers. Our agricultural industry depends on them. We must demand the same borderless world that corporations and capital live in. We must demand that worker rights be the same for all workers, citizens and migrants alike.

For those of us who oppose colonialism and imperialism, we must recognize that contract labor perpetuates those systems of oppression.

-

New Challenges for the China-Mexico Trade Relationship in 2026

The lack of high-level dialogue between China and Mexico has eroded the possibility of effective coordination in multiple bilateral areas, particularly in foreign trade.

-

Attack on Venezuela: Mexico’s Response

An interview with Daniela González López of Observatorio de Derechos Humanos de Los Pueblos.

-

Critical Minerals: Subordination

The risk is clear: Mexico’s mining, environmental, & investment policies can be progressively shaped to comply with Washington’s parameters, while a model of coordinated dependency becomes the regional norm.