The Role of Economists in National Transformations

This article by Carolina Hernández Calvario originally appeared in the August 14, 2025 edition of Contralínea. The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Mexico Solidarity Project.

Every social transformation entails an economic-political debate surrounding the new direction to follow. That’s why I dedicate this column to reviewing some of the main economic approaches that emerged in each of the transformation processes preceding the Fourth Transformation. This is intended to present, in the next installment, the economic discussions that took place between neoliberals and developmentalists in the mid-20th century, with the intention of putting future discussions into context.

During our country’s independence process (Mexico’s first transformation), liberalism presented itself as an economic vanguard, due to the merit of establishing the logical-economic arguments that allowed it to reveal the falsity of the origin of the wealth of the exploiters represented in the form of landowners, and the legitimization of their power by divine mandate.

This approach, developed in the emblematic work entitled An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, written by the Scottish philosopher Adam Smith, contributed to the establishment of the discipline of economics as a science and was a reference for José María Luis Mora in his efforts to reduce colonial monopolies and ecclesiastical control over land. This generated interesting debates with the conservative Lucas Alamán, in his efforts to defend a protectionism aimed at preserving colonial economic institutions, for the benefit of the Creole elite.

Years later, with the rise of the liberals to power with the triumph of the Ayutla Revolution, the Second Transformation took place and with it the beginning of important economic reforms, which paved the way for new historical directions in 1859, with figures such as Melchor Ocampo, the Lerdo de Tejada brothers, Ignacio Zaragoza, Guillermo Prieto, Francisco Zarco and Benito Juárez at the head who, according to Jesús Silva Herzog (1967b:180), were “the first Mexicans demonized with the label of communists – with the exception of Morelos, thus nicknamed years before by Lucas Alamán”.

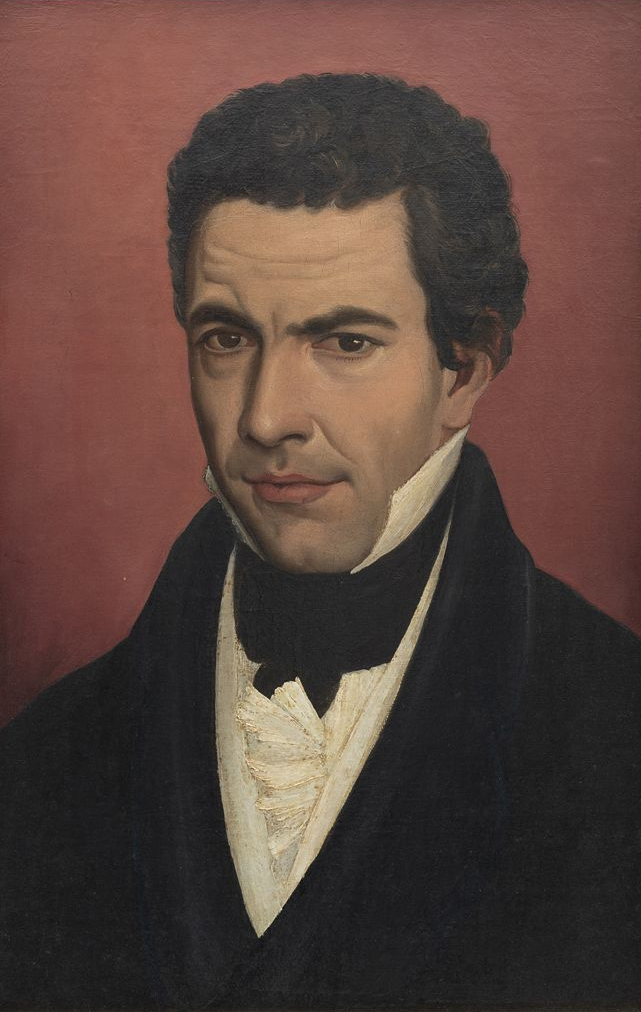

A highly fallacious description, but one that fits into a context in which great Mexican thinkers began to emerge, such as Ignacio Ramírez—the Necromancer—who was one of the most prominent representatives of Mexican social liberalism and who clearly inaugurated in Mexico what I dare to call today the critique of political economy. This thinker, by breaking away from the rationalist natural law typical of his time, managed to clearly pose a radical critique of nascent capitalist relations of production in Mexico, identified by the intellectual as the true social problem. Hence the focus of his work on emancipating day laborers from the capitalists.

As can be seen, this illustrious Guanajuato native was clear enough to identify the two antagonistic social classes that were beginning to emerge in our country: those who lived off their own labor (which the author calls day laborers) and those who lived off and enjoyed the alienated accumulated labor of the first class (the so-called capitalists). He even argued that individual enrichment was not exclusive to one’s own labor, as Reyes Heroles (1974:670) recalls, based on the following quote: “No individual becomes rich with his own labor: personal labor can ensure the subsistence of a family; but only the labor of others produces wealth.”

These two lines were published in 1875, that is, just 10 years after Capital went to press. This reflects the avant-garde that was emerging in Mexican economic thought, especially considering that the first publication in Spanish of Karl Marx’s most emblematic book wasn’t published until 1931 in Spain, and it wasn’t brought to Mexico until 1942 by Wenceslao Roces (Garciadiego, 2016).

Later, and still within the framework of the Third Transformation, the proposal to create a bachelor’s degree in economics emerged in our country, spearheaded by Jesús Silva Herzog. This project was promoted with the intention of rebuilding the Mexican state once the revolutionary process was over, with the explicit purpose of training experts to replace the engineers and lawyers who until then had been responsible for performing technical functions in both public and private finance.

The profile of the economist promoted in the early years of the program was very clear. In the words of Guillermo Domínguez (2006:55), the goal was to make “a graduate with a solid theoretical background, committed to the nation, concerned about the country’s social needs, with an ethical and social commitment.” We recall that in those years, universities were conceived as the space in which professionals with a clear conscience and a revolutionary mindset should be trained.

In the words of Narciso Bassols (1964: 432), another of the founding members of the economics career in our country: “the University does not have to continue training outdated, absurd, anti-economic, anti-revolutionary, deeply pernicious professionals”, and he concludes by saying “not a single peso of the nation’s assets will have to be allocated to the training of said professionals”, because for the author they did not contribute to the social improvement of their time.

Hence, in our country, economics as a science emerged with all the baggage of political economy and with a marked sense of humanism. In the conception of Jesús Silva Herzog (1967), the purpose of this science is the human being and its reproduction. He emphasized that the scientific objective of this discipline is not wealth for its own sake, but rather the development of strategies to improve the essential aspects of individual and collective human existence.

References

Bassols, Narciso. 1964. Higher Education in Mexico. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica

Domínguez, Guillermo. 2006. The Knowledge of the Mexican Economist. Mundo Siglo XXI Magazine

Garciadiego, Javier. 2016. The Fund, the House, and the Introduction of Modern Thought in Mexico. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Silva Herzog, Jesús. 1967. To a Young Mexican Economist. Mexico: Editorial Companies.

Silva Herzog, Jesús. 1967b. The Economic, Social, and Political Thought of Mexico 1810–1964. Mexico: Mexican Institute of Economic Research.

Carolina Hernández Calvario is an academic at the Universidad Autónoma de México (UAM) in Iztapalapa. She earned her bachelor’s and doctorate degrees in economics from the Faculty of Economics at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), and her master’s degree in Latin American studies from the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters. Her field of specialization is political economy.

-

People’s Mañanera February 18

President Sheinbaum’s daily press conference, with comments on Zacatecas housing, reform of gold-plated public pensions, Cuba, and energy sovereignty.

-

Workers Party Proposes to Guarantee Two Days of Rest

The deputies propose to reform Article 123 of Mexico’s Constitution to guarantee the right of two days of rest for every five days of work.

-

Workers To Take Over Matamoros Maquiladora

The plant is one of the auto parts factories linked to First Brands Group, which declared bankruptcy at the end of January after executive fraud revelations.