Cárdenas, in the Crosshairs of the Cold War

This article by Mireya Cuéllar appeared in the May 29, 2002 edition of La Jornada. The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Mexico Solidarity Project.

After World War II, the bipolar division of the world gave rise to a silent confrontation between powers that became known as the Cold War. Each country, depending on its alignment with the opposing blocs, developed its own distinctive features. Thus, in Mexico, it acquired the characteristics of a dirty war, where the police state took precedence over the concept of national security. Any opposition to the regime was considered a potential enemy, to be spied on and, in many cases, persecuted and fought with legal tricks or openly outside the law.

“The destruction of the past, or rather of the social mechanisms that link the contemporary experience of the individual with that of previous generations, is one of the most characteristic and strange phenomena of the end of the twentieth century. For the most part, the young men and women of this turn of the century grow in a sort of permanent present with no organic relation to the past of the time in which they live.” – Eric Hobsbawm

Fearing that General Lázaro Cárdenas was organizing pro-communist peasant militias, the government of Adolfo López Mateos ordered, in 1961, spying on the former President, preparing a team of agents from the Attorney General’s Office dedicated to determining whether the old military man – by then enamored with the Cuban Revolution – was “stirring up tempers, inviting revolution or other unrest.”

Lázaro Cárdenas had the government worried. After 20 years of silence—a situation that earned him the nickname “the Sphinx of Jiquilpan” in the press—the former President reappeared in public life supporting the rebel movement that had triumphantly entered Havana on the last night of 1958.

The event stirred and polarized Mexican society. A segment of society—intellectuals, members of the Communist Party, and leftist movements—received the event with enthusiasm, while the Catholic Church fueled anti-communism among its parishioners, organized 36-hour prayer sessions among the upper middle class to pray that the communists would not reach the country, and called on peasants in the villages to fight “the atheists.”

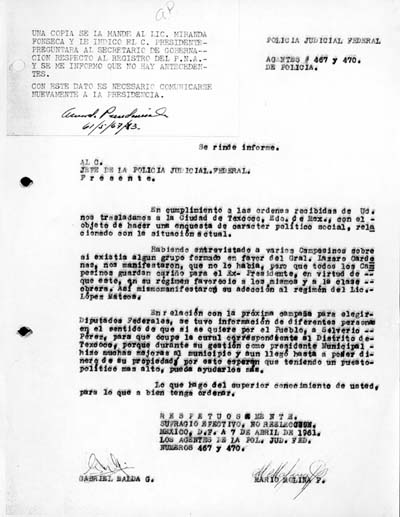

“In compliance with the orders received from you, we have traveled to the city of Texcoco, State of Mexico, in order to conduct a political and social survey related to the current situation (….) Having interviewed several farmers to see if there was any group formed in favor of General Lázaro Cárdenas, they told us that there was not, but that all the farmers are fond of the former President, because during his regime, he favored them and the working class. They also expressed their allegiance (adherence) to the regime of Mr. López Mateos…”

This report – spelling and syntax as is – sent on April 7, 1961, by agents of the Federal Judicial Police number 467 and 470 (Gabriel Malda and Mario Molina) to their boss, is one of many that agents of that institution reported to their superiors throughout the country in the fateful year of 1961.

A public message from Commander Fidel Castro set off alarm bells in government circles. U.S. President John F. Kennedy seemed on the verge of ordering an invasion of Cuba—the triumph of a popular revolution 166 kilometers from their territory had been an “electric shock” for the Americans, according to researcher Soledad Loaeza—and on Sunday, March 27, the bearded guerrilla said in Havana that “the peasants of Mexico are ready to take to the mountains in defense of the (Cuban) revolution if our homeland is attacked.” He added that General Cárdenas “is the leader of all the humble people of Mexico, men and women, and of the Mexican soldiers.”

The news, published in a scandalous tone on the front pages of the Mexican press, along with calls for “help” for Cuban refugees fleeing communism that “took away their homes and possessions,” and the extensive explanations of what the “red and atheist tyranny” entailed, depict the polarization of the era, a reflection of the Cold War that was raging at the time.

The Michoacán general was forced to respond to these rumors, and on March 31, he published a letter in Excélsior clarifying that Castro’s statement referred to the “solidarity” that had been expressed during a Latin American conference convened days earlier. “The Cuban prime minister is not appealing to the peasants of Mexico…” he clarified.

The government, however, did not remove his personal detail. A few days before the speech given by the commander of the Cuban Revolution (who formally declared himself a socialist in 1961), General Cárdenas convened and organized the Latin American Conference for National Sovereignty, Economic Emancipation, and Peace, attended by delegates from China, the USSR, Argentina, Brazil, and Cuba.

The conference took place in an atmosphere rendered “unbreathable by the stinking bombs” thrown by a group of anti-communist students, and where Patricio Lumumba, the Congolese leader, and Castro “were the two names constantly cheered at the opening session,” according to Excélsior. The presence of Vilma Espín de Castro, Raúl’s wife, drew the attention of the press in general.

The order to monitor the general came directly from the president to the Attorney General of the Republic, who personally delivered the reports to López Mateos during the negotiation sessions. Lázaro Cárdenas not only organized conferences in support of Cuba, but during the Bay of Pigs invasion, he also attempted to travel to the island to participate in its defense.

Anti-Castro planes were already flying over Cuban territory when, very early on April 17, a report was delivered to the attorney general stating that the general, his wife, his brother Dámaso, Congressman Horacio Tenorio, and an aide to the former President had reservations for flight 311 to Havana that day at 8:20 a.m., “but due to the current conflict, the flights were suspended.”

Cárdenas del Río spent the entire day at the airport trying to find a way to get to Cuba. There, too, he was followed minute by minute. A Telephone Report from the Central Air Port, captioned “Federal Judicial Police” at the top, which, like all documents related to the spying on the general, is on PGR letterhead, reads:

”At 2:45 p.m., police officer Jesús Madrigal Nieto reports that General Lázaro Cárdenas is at the airport, where he was interviewed by reporter Olguín. He stated that he condemned the crime being committed against Cuba by Yankee imperialism and that the Government and People of Mexico, as well as all free Governments and Peoples, must protest this aggression. At this moment, the General was ready to leave for Havana…”

“When reporter Olguín asked him if he wasn’t afraid of going to Cuba in the current situation, the General replied that that was precisely why he was going.”

“Our Agent continues to report that the special flight that will take General Cárdenas is likely to be carried out on an Aerovías Anaya plane…”

Ultimately, the flight didn’t take place that day, nor the next, but instead later in July of that year. The last report that afternoon regarding his activities was: “General Lázaro Cárdenas has suspended his trip, but he will possibly depart for Havana tonight or tomorrow morning. Our agents will be on the lookout, as Aerovías Anaya has already submitted a request to take him to Mérida, Yuc., and possibly from Mérida, board another plane” (to reach Havana).

As his efforts to leave were in vain, on April 18, he participated in a mass rally held in the Zócalo, protesting the invasion of the island. Cárdenas surprised many when he climbed into the trunk of a car, from where he delivered impromptu speeches and demanded that the Mexican government “adopt a frank stance, as the people of Mexico must also adopt, and, if necessary, go to war against imperialist impositions.”

The “DF Police Headquarters” submitted a report on its participation in that rally:

Summary of the speech given by Major General Lázaro Cárdenas during the rally held at 8:30 p.m. today in Constitution Square, protesting the attack on the Republic of Cuba. Approximately 10,000 demonstrators gathered…

”The attack on Cuba was carried out by forces that came from abroad (said Cárdenas, according to the report) (…) he compared the case with the aggression suffered by the Mexican Revolution (…) WE MUST BE ON WAR FOOTING (the original is in capital letters), because the same thing that is happening now to Cuba can happen to any country in Latin America.”

During the rally, according to press reports, former President Cárdenas commented that no airline company would transport him and that when he tried to book a private flight, “the same airlines blocked him, even threatening the pilot who was going to make the trip.” He reported that he had previously informed the President that he was planning to go to Cuba, and that it was a trip already planned.

The former President’s pro-Cuban stance earned him a criminal complaint from the National Anti-Communist Party—which had its offices on Liverpool Street and was headed by Mario Guerra Leal—accusing him of “treason” for “attempting to establish a communist-type totalitarian regime.” The middle classes were not, as has sometimes been presented, revolutionary, and his pro-communist stances and the assault on the Madera barracks in Chihuahua on September 23, 1965, provoked the rejection of those who had believed the story of the “Alemanista Mexican miracle.”

The extensive file in the government archives of the period—which the government will soon make public—reports the General’s movements during a good part of Adolfo López Mateos’s six-year term. It includes leaflets, advertisements published in newspapers of the time, and reports from the police officers charged with investigating his activities. There are also some copies of documents from the Ministry of National Defense regarding the military officer’s actions.

Despite the criticism he received at the time, Lázaro Cárdenas maintained his stance. He went to Cuba to celebrate the assault on the Moncada Barracks and, in August 1961, spearheaded the birth of the National Liberation Movement (MLN), a unity of the “democratic and anti-imperialist” forces.

The MLN’s lifespan was short. Enrique González Pedrero, Víctor Flores Olea, Carlos Fuentes, and other intellectuals participated with the General in his movement, despite the censure of the radical left.

It was the Mexico in which the ruling class could kill agrarian leaders like Rubén Jaramillo with total impunity. It was the Mexico that danced in the capital’s salons to the rhythm of Sonora Santanera and the voice of Sonia López, and that had César Costa and Julissa as its “rebels without a cause” for mass consumption.

The General continued to move to the left. His support for the creation of the Independent Peasant Central in 1963, an organization closely tied to the then-banned Communist Party, earned him strong criticism from the PRI and a letter of rebuke from former President Emilio Portes Gil, accusing him of supporting “shameful communists” who “are unfairly attacking López Mateos.”

Lázaro Cárdenas del Río turned his attention to the Institutional Revolutionary Party again during Gustavo Díaz Ordaz’s presidential campaign, when he received him in Michoacán as head of the Balsas River Commission. By then, the Communist Party had abandoned its old political strategy of “promoting” the Mexican Revolution, José Revueltas was accused of being a “revisionist”… and many young people had opted for guerrilla warfare during a six-year term that, in López Mateos’ own words, was “leftist… within the Constitution.”

-

Let’s Talk About Migration: Trumpist Persection

Millions of women who have endured unspeakable violence on their migration journey are now being persecuted in the United States by an extremely xenophobic and misogynistic government, led by Donald Trump,

-

Culture | Labor | News Briefs

Workers Occupy Culture Secretariat, Demand 13% Wage Increase

2,000 workers have been receiving incomes below Mexico’s minimum wage for over two years.

-

People’s Mañanera March 2

President Sheinbaum’s daily press conference, with comments on electoral reform, the gradual move to a 40 hour workweek, employment, national security strategy, and once again, the call for peace.