Mexico’s Green Party Has Served Neoliberals, Salinas Pliego & the 4T. Its Franchise Model is in Danger.

This article by Blanca Juárez originally appeared in the January 28, 2026 edition of Sin Embargo.

Mexico City. The Green Party of Mexico (PVEM) has been more of a franchise than a political force. Since its inception, it has placed its electoral profitability at the service of the winning party in power, thus becoming a “key” to passing or blocking reforms. Its clients or partners range from TV Azteca to the current administration. Now, facing a crucial moment—the debate on electoral reform—the toucan party seeks to maintain its business and prevent the reduction of proportional representation seats and its funding, where its strength lies.

By 2026, the PVEM has an annual budget of over 859 million pesos ($50 million USD). Public money in a party whose control remains in the hands of the González family and which is, to a certain extent, distributed among other men: primarily Manuel Velasco and, later, influential figures such as Arturo Escobar y Vega, Carlos Alberto Puente, and Luis Melgar Bravo.

The Green Party’s Declaration of Principles makes no mention of extractivism or other neoliberal dynamics as the structural causes of environmental damage, much less any intention to address or resolve them.

“It’s a profoundly right-wing party,” contradicting its supposed environmental platform, which would be more aligned with progressivism, said José Antonio Carrera Barroso, former advisor to the General Council of the National Electoral Institute (INE), in an interview. The Green Party has always been “linked to businesspeople, and moreover, to a certain group of businesspeople,” he emphasized.

Clear examples of what the academic from the Autonomous Metropolitan University (UAM) Iztapalapa mentions are Senator Luis Melgar Bravo, who has worked for Grupo Salinas since at least 2001. For 25 years he has held various positions in the different companies of Ricardo Salinas Pliego. Or Carlos Puente, another former executive of TV Azteca.

Other cases could be added to that list, such as that of the Mayor of Santa María Huatulco, Julio Cárdenas, a former member of the PRI party who has also allied himself with Salinas Pliego’s interests. The Green Party mayor, for example, did a “double favor” for a Salinas Pliego company by allowing it to pay the property tax on a plot of land where a golf course is located—a course the businessman is disputing with the federal government. In addition to facilitating the payment, the Green Party politician granted a 99 percent reduction in the property tax, as revealed in the program Los Periodistas.

The truth is that within this political force there are other figures and legislators from the PVEM who are at the beck and call of this oligarch: One is Deputy Puente Salas, aspiring governor of Zacatecas, who has been his political operator since he joined Televisión Azteca in 1994.

Melgar Bravo and Puente Salas have in common, besides being part of the PVEM leadership, having been members of the “television caucus” during the six-year terms of Felipe Calderón and Enrique Peña Nieto, when deputies and senators from this party and the PRI defended the interests of Televisa and Televisión Azteca, and in general of the radio and television industry, a cast that also included, as Senator and Deputy, Ninfa Salinas Sada, the daughter of Salinas Pliego.

In that sense, after almost three decades, the Green Party (PVEM), while not an electoral giant, has become indispensable to the current administration. The party has achieved disproportionate power, since its strength lies not in elections, but in Congress, where its votes tip the scales. And if it doesn’t support Morena in the electoral reform, the reform “won’t move forward.”

“They have a broad capacity for negotiation and will hardly give up on these two things that have historically favored them: the budget and proportional representation,” says José Antonio Carrera, professor-researcher in the Department of Sociology at UAM-I.

The Franchise Game

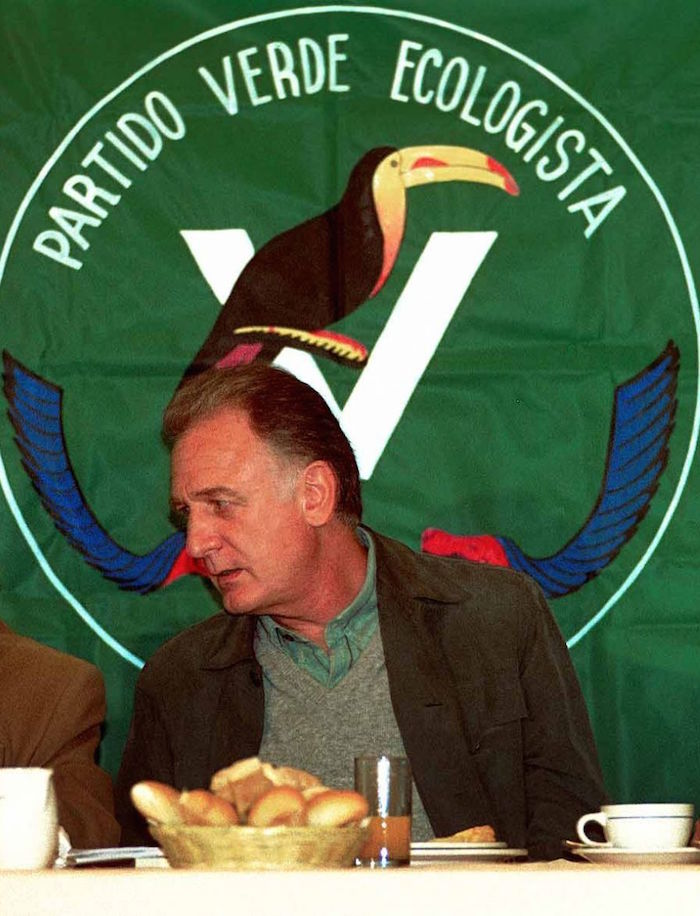

The Green Party (PVEM) was created between the 1980s and 1990s by Jorge González Torres, son of Roberto González Terán, owner of Farmacias Fénix. As Paula Sofía Vásquez Sánchez and Juan Jesús Garza Onofre recount in their book, La mafia verde (The Green Mafia), Jorge González took advantage of a citizen environmental movement in the Pedregales de Coyoacán, Santa Úrsula, and other neighborhoods of Mexico City.

It gradually gained traction until that man who wore leather jackets appropriated the cause and secured its registration as a national political party. The Green Party (PVEM), whose primary focus should be the environment, has never had a genuine connection with the Indigenous and community movements that have historically defended life and territories against extractive industries.

It was born in incongruity and so it continued.

It was also born with the support of the PRI. Former President Carlos Salinas de Gortari instructed that the creation of this party be supported, but not without a price. Manuel Camacho Solís, the person in charge of bolstering this political organization, acknowledged that candidates were “suggested” to him, according to Vásquez Sánchez and Garza Onofre in their investigation.

In 1994, the Green Party (PVEM) nominated Jorge González Torres as its presidential candidate. However, in 2000, it allied with the National Action Party (PAN) in support of Vicente Fox and won 17 seats in the Chamber of Deputies. From 2006 to 2021, it returned to the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), seeing that electoral trends were once again favoring that party; Enrique Peña Nieto was their candidate, for example. During that period, it increased its number of seats in the Chamber of Deputies, reaching a peak of 38.

His talent has been identifying the winner. So in 2021, with a very different political and electoral landscape, he went with Morena. Having supported candidates like Jorge González, Fox, and Peña, in 2024 his presidential candidate was Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo. And the current balance in the Chamber of Deputies is 62 seats, the highest in its history.

If one had to define the political ideology of the Green Party, it would be the “ideology of opportunism,” quips José Antonio Carrera. It is not an environmental party, he states emphatically. Throughout all these years, the PVEM has operated based on “electoral calculations” that benefit its leadership and a select few, not the environment. Its agenda is aligned with its chosen partner.

But the party system in Mexico has also favored the PVEM’s commercial strategy, turning it into a business. To begin with, “it has been said that we are in a one-party regime, which is false. Nor do we have a hegemonic party regime,” with Morena holding the majority, says the academic.

What exists “is a competitive, dominant-party system, where the PRI and PAN have lost their ability to form coalitions and their veto power. And the Green Party has become the party with which reforms can be implemented. And therefore, a key player in political negotiations.” This is the case with the Electoral Reform.

Then, “being a political party in this country is already quite profitable. They are the only institution with a guaranteed budget at the constitutional level,” notes José Antonio Carrera. For 2026, the INE (National Electoral Institute) allocated the PVEM (Green Party of Mexico) a budget of over 832 million pesos under the heading “Maintenance of Permanent Ordinary Activities.” Plus another almost 25 million for “Specific Activities.” Therefore, it has over 859 million pesos at its disposal.

The other party that has formed alliances, the PT, received just over 690 million pesos this year. That’s about 170 million less than the Green Party. Some 40 years ago, Jorge González Torres saw a gap in the electoral market: environmentalism. The gains are clear.

“They (in the PVEM) have understood that they are not going to be a party that will achieve power. They are going to accompany power,” analyzes José Antonio Carrera.

A Green Family

In addition to being right-wing, José Antonio Carrera defines the PVEM as an elitist party that “isn’t interested in having a membership. They are happy and content with the votes they are getting, and the political situation led them there for various reasons.” Because what they represent are “private interests” and not those of the citizenry

As unique as those of a family. Until 2001, the party president was Jorge González Torres, the Toucan Man, as Paula Sofía Vásquez and Juan Jesús Garza call him. He retired, but left his son, Jorge Emilio González Martínez, the Green Kid, in charge.

From then on, the authors of The Green Mafia say, the PVEM’s politics of expediency and blackmail intensified. At least the father maintained “minimal points of consistency,” such as an environmentalist discourse, but “all of this seemed to get in the way of the junior,” they note in their book.

Under the leadership of Jorge Emilio González, in 2009 the party began a campaign to promote the death penalty for kidnappers and murderers. As a result, the European Green Party (EVP), which at the time comprised 36 political parties from 32 countries, severed ties with the PVEM. Green is life, but not for this family-run franchise.

Although Jorge González’s brothers, Víctor González (owner of Farmacias Similares) and Javier González Torres (owner of Farmacias Fénix and Farmacias de Genéricos), are not members of the party, they have benefited from the reforms the Green Party has negotiated, which is why they now oppose the Electoral Reform. In 2010, they promoted a reform so that when the Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS) did not have a prescribed medication in its pharmacies, a voucher redeemable at private pharmacies would be issued.

In 2011, Jorge Emilio González stepped down as President of the Party and was succeeded by Carlos Alberto Puente Salas. In 2020, Karen Castrejón was elected national president of the PVEM by the National Political Council.

Although she has had a political career, as a legislator and as Secretary of the Environment and Natural Resources of Guerrero, in the Government of Héctor Astudillo, for José Antonio Carrera this election followed the old pattern of instrumentalizing social demands of the Green Party.

She was elected “in this wave in which parity and gender violence took on a predominant role in political discourse. So, the PVEM, in this opportunism, said ‘we are going to put Karen and Pilar Guerrero Rubio as Executive Secretary to comply with what is happening in the country, which is parity and the fight against gender violence.’”

In reality, Raúl Bolaños Cacho or Carlos Alberto Puente have more power, he says. And of course, Manuel Velasco, who knew how to exploit the friendship his grandfather, Fernando Coello Pedrero, had with Andrés Manuel López Obrador to jump from the PRI to Morena.

The Green Party’s Centralized Power

“The Green Ecologist Party of Mexico represents a socially based current of opinion: the environmentalist one,” states its Declaration of Principles. It notes that “the party wishes to achieve an environment that can be enjoyed by all living beings.” And it defines the environment as “a whole comprised of air, land, water, and sun.”

However, it makes no mention of extractivism or other neoliberal dynamics as the structural causes of environmental damage, much less any intention to address or resolve them. In fact, it refers to what environmental, Indigenous, and land rights movements call the “climate crisis” as “climate change.” The first term naturalizes the problem, while the second presents it as a consequence of an economic and political model.

Also in its Declaration of Principles, the PVEM affirms the need to establish democratic forms of coexistence in society, political parties, and government. It asserts its desire to contribute to building a genuinely democratic culture.

However, within its party structure, the National Political Council (CPN) holds centralized power. It is above the National Executive Committee (CEN), which is chaired by Karen Castrejón.

According to its Statutes, the CPN approves “coalitions, fronts, or alliances in any form” with other political parties. It also approves candidacies for the federal Congress. Among other powers, it is the body that can approve, modify, or repeal regulations.

Manuel Velasco Coello appears first on the list of members of the CPN. Other members include Arturo Escobar y Vega, José Ricardo Gallardo Cardona (Governor of San Luis Potosí), Jesús Sesma Suárez, Carlos Alberto Puente Salas, and Karen Castrejón Trujillo. In total, there are 26 council members elected by the National Assembly.

Within its party structure, the PVEM includes the categories of members, supporters, and sympathizers. Members have full rights to participate and vote in internal elections. Supporters have less influence on decisions. And sympathizers receive information and participate in activities, but without decision-making power. However, this is how they have managed to integrate external figures into their candidacies.

-

Veracruz: Oil Spill Victims Complain Of Insufficient Action by State Government

Residents of Pajapan, who live around Laguna Ostion, demand that the authorities take prompt intervention to solve the hydrocarbon spill in the southern part of the state of Veracruz.

-

San Luis Potosí Goodyear Workers Threatens Strike After Salary Increase Refusal

While Mexico’s general minimum wage has had a real increase of 116% in the last seven years, SITGM workers have received only 15.2% increases in the same period.

-

FIFA’s Cola Cup & Dystopian Horror

The World Cup’s arrival in Mexico is a stark illustration of the absurdity of the world we’ve reached thanks to the power of large corporations; of the crisis of our current civilization, a society trapped in a power economy, manipulated by addictions.